- PureCycle is the latest zero-revenue, ESG-themed SPAC taken public with a bold story about how it will someday revolutionize the plastics recycling industry.

- The company’s insiders and SPAC sponsors do not seem inclined to wait to see how its claims will work out: they’ve collectively positioned themselves to clear ~$90 million in cash and tradable shares before the company generates a single dime in revenue.

- PureCycle’s Chairman/CEO and other associated executives collectively took 6 companies public prior to PureCycle. All have failed, resulting in 2 bankruptcies, 3 delistings, and 1 acquisition after a ~95% decline. Over $760 million in public shareholder capital was incinerated in the process.

- We spoke with multiple former employees of these earlier failed companies, who said PureCycle’s executives based their financial projections on “wild ass guessing”, brought companies public far too early, and had deceived investors.

- PureCycle executives have already begun to cash out, receiving $7 million in cash bonuses for simply closing the SPAC deal, and are slated to receive ~$40 million in compensation before any revenue is generated.

- PureCycle’s SPAC sponsors are two investment banks, Roth Capital and Craig Hallum Capital, who collectively received ~2 million ‘founders’ shares for a little more than a penny per share, worth about $48 million at today’s share price.

- Roth has an odious reputation and is well-known for having brought numerous Chinese companies public on U.S. exchanges that later imploded after fraud allegations. Roth facilitated several of these IPOs, issued “buy” ratings on the companies through its research department, then left public investors holding the proverbial bag. Its activities earned the bank a prominent role in the documentary “The China Hustle”.

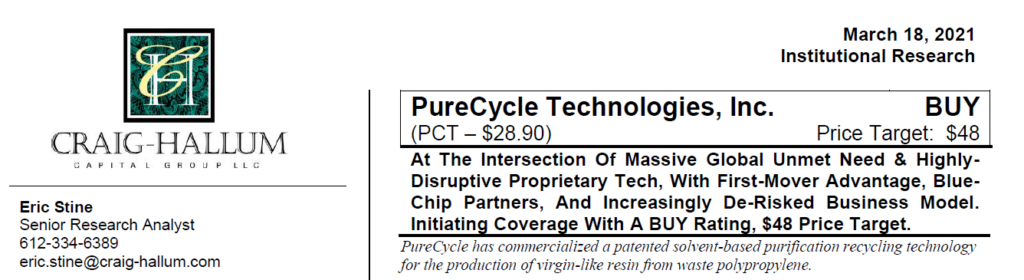

- Roth and Craig Hallum are the only investment banks that have issued research on PureCycle. Both have “Buy” ratings with targets between $45-$48. Two partners in Craig Hallum’s “research” division received founders shares for ~1 penny per share, including the company’s Co-Director of Research.

- Unlike in traditional IPOs, where dealrunners must observe a “quiet period” before commenting publicly on a new issue, Craig Hallum’s research department issued a “Buy” rating the very day of PureCycle’s SPAC merger, sending shares surging.

- Many leading plastics companies publish peer reviewed studies that detail their advancements in the field. Contrary to that norm, we were unable to find a single peer reviewed study in any scholarly journal citing or reviewing PureCycle’s licensed process.

- We spoke with multiple competitors and industry experts who explained that PureCycle faces steep competition for high quality feedstock, and called the company’s financial projections into question.

- We consulted with a 30-year expert on polymers, with a background in advanced plastics recycling. He told us the company’s patent is “indirect”, “vague” and a “regurgitation” of prior art.

- Our expert also referred to the company’s flammable pressurized process as a “bomb” and warned about the company forging ahead to commercial scale despite still having issues at a lab scale.

- In our opinion, PureCycle represents the worst qualities of the SPAC boom; another quintessential example of how executives and SPAC sponsors enrich themselves while hoisting unproven technology and ridiculous financial projections onto the public markets, leaving retail investors to face the ultimate consequences.

Initial Disclosure: After extensive research, we have taken a short position in shares of PureCycle Technologies. This report represents our opinion, and we encourage every reader to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report.

Introduction

PureCycle is the latest zero-revenue, ESG-themed SPAC to be taken public with a bold story about how it will someday “revolutionize” the plastics recycling industry.

The six-year-old company based in Ironton, Ohio, aims to commercialize a process for recycling polypropylene (PP) a common plastic used in everything from carpets to shampoo caps to fishing nets. [Pg. 1]

While it makes for a great sounding “green” story, plastics recycling has been a perpetual challenge from an economic standpoint. The industry has struggled with the economics of even the most basic plastic recycling for decades, as documented in a 2020 NPR exposé titled “How Big Oil Misled The Public Into Believing Plastic Would Be Recycled”.

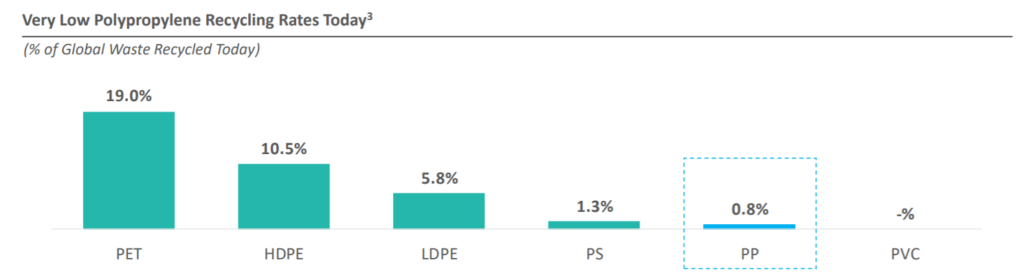

Within plastics recycling, PP has been particularly uneconomical. PP represents 28% of the world’s plastic, yet currently only ~0.8% of it is recycled today. [Pg. 10]

This is because a sizable amount of PP requires expensive sorting and cleaning due to its use in food packaging. It is also commonly found in products that use mixed plastics that can be difficult to separate. These dynamics have rendered PP recycling largely uneconomical despite the world’s top scientists and major chemical companies seeking a solution since PP’s discovery in 1951.

Enter PureCycle, which hopes to use patented recycling technology licensed from plastics producer Procter & Gamble to scale a process for recycling PP profitably, a goal that all major plastics companies have failed to achieve to date:

“Up to this point it’s been impossible to recycle plastic into pure, virgin-like form. But here’s the thing. At PureCycle Technologies, the word impossible is not in our vocabulary.”

Investors in PureCycle seem most excited about the company’s relationship with (a) Procter & Gamble, from which it licenses its technology, and (b) agreements with a several other major plastics producers such as L’Oreal, and Total SA to purchase its product should the company ever succeed at scaling its process for producing virgin-like consumer-grade plastic.

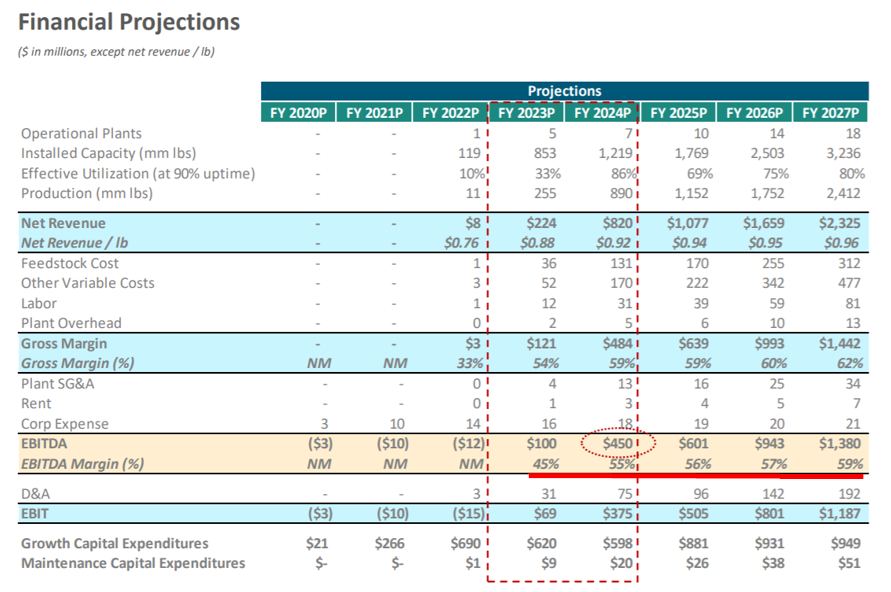

In 2017, PureCycle announced that it aimed to generate revenue from its “commercial scale production facility in late 2020”.[1] The latest company presentation has revised that target to late 2022, at the earliest, when it hopes to finish most of the commercial “Phase II” portion of its plant and generate $8 million in revenue. [Pg. 1, Pg. 29]

From there, the company boldly projects $224 million of net revenue in FY2023, which it then plans to grow nearly ten-fold—to $2.3 billion by 2027.

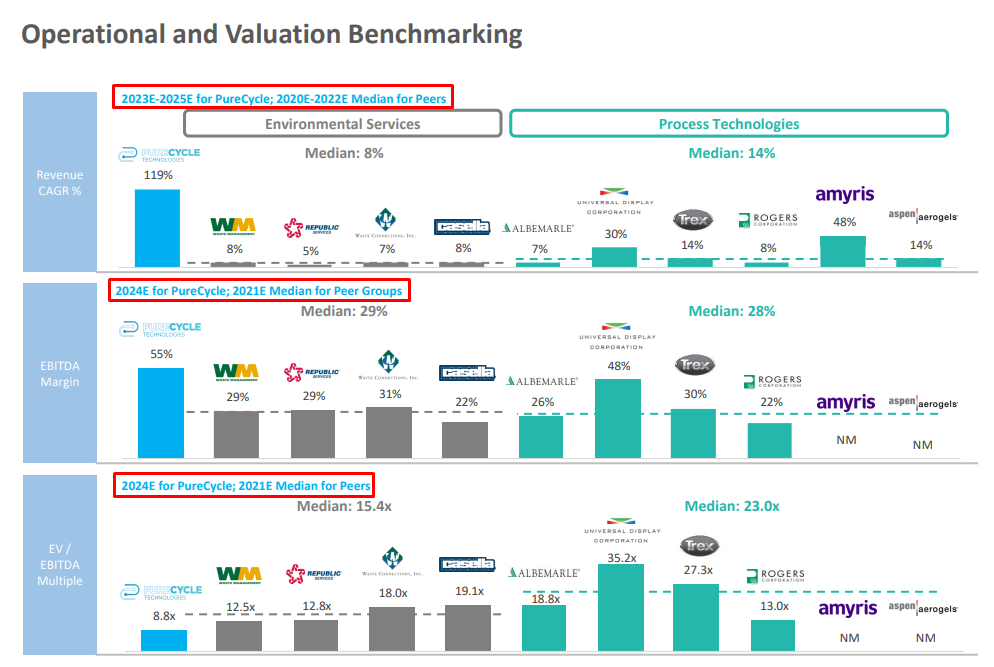

The company then put its aggressive projections through a bit of a torture session in order to justify its valuation. For example, in its November presentation, PureCycle presents a valuation analysis that compares PureCycle’s 2023-2025 projections alongside 2020-2022 medians for its competitors. [Pg. 32]

Perhaps more eyebrow-raising are the company’s projected profitability figures; 45% EBITDA margins that expand to 59% by 2027. [Pg. 29]

In a corner of the plastics recycling world that has eluded economic sustainability for the world’s top chemical companies, those numbers would put PureCycle’s margins on par with some of the world’s most profitable tech companies.

Despite the lack of any current production and revenue since its inception, the company has a current market valuation of $3.1 billion, and an enterprise value of ~$2.8 billion, owing to the $308 million in cash it raised through its SPAC and PIPE rounds. [Pg. 3]

SPAC Sponsor Roth Capital Is an Investment Bank With a History of Taking Dubious Companies Public Then Slapping Glowing “Buy” Ratings On The Stocks, Leaving Public Investors Ultimately Holding the Bag

PureCycle went public through a merger with a SPAC named “Roth CH Acquisition I”, which was sponsored by investment banks Roth Capital and Craig Hallum Capital (CH).

Roth Capital is an investment bank based in Newport Beach, California that largely operates in the murky world of small cap and microcap banking.

The firm has developed an odious reputation in the financial community. Whereas most of Wall Street repudiated the frat boy ethos after the “Wolf of Wall Street” era in the 1980’s, Roth never seemed to have given it up. In 2007 the company held an investor event where “[t]he primary feature . . . was the presence of ‘several dozen’ topless Asian models, with the ticker symbols of the companies Roth underwrote body-painted on.”

Roth’s FINRA BrokerCheck report shows 27 disclosures, comprised of 15 regulatory sanctions and 12 arbitrations. In one instance, Roth was cited for violations of Regulation M (which focuses on preventing market manipulation) while it acted as the managing underwriter in a public offering.

Roth is also well-known for its role in facilitating numerous suspect reverse mergers involving Chinese companies, raising approximately $3.1 billion for China-based clients from 2003 to 2012. Roth regularly took companies public then slapped glowing “Buy” ratings on the stocks through its research division.

For example, Roth was involved in the IPO of China Electric Motor, then issued 5 “Buy” ratings on the company. About a year after the IPO, the stock was halted over financial discrepancies and delisted, while the company was the subject of numerous investor lawsuits.

Many other similarly situated Roth clients subsequently became entangled in allegations of fraud, leaving retail investors holding the bag. [1,2,3]

Roth’s activities earned it a prominent role in The China Hustle, a documentary about Chinese financial fraud imported onto U.S. exchanges via such reverse mergers.

Roth Sponsored the PureCycle Transaction, Then Slapped a “Buy” Rating and $45 Price Target On The Stock A Week After A Portion of Roth’s Shares Became Eligible To Dump

Investment banks Roth Capital and Craig Hallum both hold substantial shares in PureCycle through their sponsorship of the SPAC deal.

The two entities and their affiliated individuals collectively received almost 2 million “founder’s shares” for a little more than a penny each for their role. [Pg. 8]

Currently, the only two investment banks whose “research” divisions cover PureCycle are Roth and Craig Hallum, the two sponsors of the deal. Both have put “Buy” ratings on the company, with price targets ranging from $45-$48.

In a typical IPO, investment banks sponsoring the deal are required to observe a “quiet period” where they cannot issue research for at least 10 days, so as not to unduly influence the price in the new issue. This doesn’t apply to SPAC transactions, so Craig Hallum issued its “Buy” rating and a $48 price target on March 18th, the very day PureCycle went public. The price surged 13% on the day.

Two fortunate recipients of the ~1 penny founders shares include partners in Craig-Hallum’s research division, including its Co-Director of Research.

The immediate surge in price helped trigger an early share unlock for Craig Hallum and Roth. Per the terms of the Founder’s Shares, half became eligible for sale on April 16th due to the elevated stock price. [Pgs. 4 & 2]

Five days after Roth’s shares were unlocked for sale, the research department at Roth issued a “Buy” rating on PureCycle, assigning a $45 price target, representing almost ~94% upside from prices the previous day. The stock leapt 6.2% for the day on the positive news.

Roth and Craig Hallum have disclosed no stock sales since PureCycle’s merger, and it is unclear when they plan to sell. It is also unclear whether any Craig Hallum-affiliated individuals have yet sold into the firm’s own “Buy” recommendation.

The rest of Roth & Craig Hallum’s founder’s shares will become freely tradable in September 2021, well before any revenue is generated by the company. [Pg. 2] Both firms stand to gain considerably regardless of how the company’s plans work out.

Part I: PureCycle’s Executives’ Uncanny Track Record of Destroying Public Shareholder Capital

Usually, successful executives are quick to publicize their track records of generating returns for shareholders. PureCycle’s Chairman/CEO’s biography, while noting his history of founding and capitalizing investments, stops short of discussing the returns of these investments.

This, we believe, is because Otworth, along with other key PureCycle leaders, have a consistent track record of destroying public shareholder capital through PureCycle’s parent firm, Innventure, and two other predecessor investment firms: (1) XL Vision, which filed for Chapter 7 bankruptcy in 2001, and (2) XL TechGroup, which formed about a year later, went public in 2004 and has been inactive since 2008.

Here’s how several PureCycle-associated executives and company Directors have played roles in these previous investment firms:

| PureCycle | Innventure | XL TechGroup | XL Vision | |

| Mike Otworth | CEO & Chairman | Co-Founder, Chair | Senior Mgmt. | VP |

| Bill Haskell | CEO | Co-Founder, Pres. | President, COO | |

| Rick Brenner | Director | COO, Co-Founder | CEO, TyraTech | |

| Dr. John Scott | Director | Chief Science Officer | Co-Founder, CEO | CEO, Chairman |

Collectively, through the above 3 investment firms, we have identified 6 companies taken public by these senior executives. All have failed. PureCycle is their 7th.

These executives seem to have no background in polypropylene recycling, yet PureCycle is now asking the market to believe that they are the team that has identified – and will commercialize – a miracle solution to one of the most challenging problems in the world of plastics recycling.

Of The 6 Companies Taken Public By PureCycle Senior Executives, 2 Went Bankrupt, 3 Were Delisted, And 1 Was Acquired Following a ~95% Decline

Over $760 Million in Public Shareholder Capital Was Incinerated in the Process

Before PureCycle announced it was going public through a SPAC in November, it was owned and controlled by Innventure, a Florida-based, startup incubator for “proven technologies.”

Innventure was founded by PureCycle Chairman/CEO Mike Otworth, PureCycle Chief Science Officer and Director Dr. John Scott, and PureCycle Board Member Rick Brenner.

Innventure’s management team takes credit for “six successful IPOs”. Here they are:

- Chromavision Medical Systems made imaging systems to detect cellular diseases.

- PureCycle Chief Science Officer and Director Dr. John Scott served as Chairman at Chromavision. ChromaVision amassed a $64.2 million accumulated deficit by end of year 2001 and received a notice of delisting in October 2004.

- eMerge Interactive was an online cattle auctioneer.

- AgCert focused on reducing emissions from pig dung.

- Bill Haskell, the CEO of PureCycle’s parent, acted as “representative” for his group’s investment in AgCert and also served as the company’s interim CEO in 2005 through at least 2007. AgCert amassed a €141.1 million accumulated deficit by mid-2007. The company delisted after “misjudging its carbon credit portfolio” in 2008 and filed for insolvency in 2012.

- TyraTech, Inc. was focused on developing insect control products.

- PetroAlgae claimed to have found a way to economically turn algae into fuel.

- PureCycle Chief Science Officer and Director Dr. John Scott served as CEO of PetroAlgae. The zero-revenue company filed to go public in 2010. PetroAlgae amassed a $73.8 million accumulated deficit by 2010. The company was delisted onto the OTC pink sheets by 2011. Scott resigned as Chairman in February 2012. The company changed its name in 2012 and ultimately had its securities registration revoked in 2017.

- XL TechGroup was a Venture Capital/incubator company that preceded Innventure.

- PureCycle Chief Science Officer and Director Dr. John Scott served as Co-Founder and CEO of XL TechGroup.

- PureCycle Chairman/CEO Mike Otworth held a C-level role at XL TechGroup

- Bill Haskell, the CEO of PureCycle’s parent, served as Co-Founder and President of XL TechGroup.

- The company IPO’d in 2004 and amassed a $189.6 million accumulated deficit, and its stock was delisted and cancelled in August 2008.

Former Employees of Executive’s Failed Public Companies: They Were Running a “Con”, Revenue Projections Were Based on “Wild Ass Guessing”, Companies Were Taken Public Far Too Early, and The Team Was “Deceiving” to Investors

We connected with former employees of several of the failed public companies led by PureCycle’s executive team referenced above.

A former senior employee of PetroAlgae told us bluntly of the management team:

“I think in some aspects they were deceiving to investors…maybe not in their minds but definitely from an engineering and scientific point of view.”

“I think they did con…that´s a strong word but I think its accurate“

The employee we spoke to told us the company’s management sold investors on a hyped-up industry.

“I think because of the biofuel boom especially in algae they were forced into the same hype as all the other algae biofuels just to get funding”.

Ultimately, he described the company as deceiving in its pitch to investors.

“I think it was deceiving to the investors and I couldn´t have done that personally. But a lot of salespeople have that mentality where they overpromise and think they can make it happen. It just didn´t at that time.”

The original business model at Petroalgae failed, so the company ditched its plan to obtain biofuels from algae to an equally ill-fated plan of growing duckweed (not an algae) for animal feedstock and human consumption. A former consultant of the company told us:

“This is not a self-supporting venture this was more a showpiece type of thing. People had money to show, in fact they had money to burn by our standards, and they were burning it by growing duckweed.”

A former employee of AgCert told us the company was “too aggressive” with forward sales projections:

“There was a lot of wild ass guessing going on there, and a warning to investors: this is speculative you could lose all your money so jump in if you want.”

He described the listing of AgCert as a “high stakes poker game”. AgCert filed for insolvency in 2012. He added:

“In retrospect (the forecasts were) too rosy obviously because we failed. We fell short of our targets and that´s how we got taken over by creditors. But on the other hand, if they had been too conservative they wouldn´t have garnered the interest for high risk investment in the first place.”

We also spoke with a former employee from TyraTech, who told us that that the executive team now at PureCycle had a model “to take [companies] to public offering as quickly as possible” and that TyraTech was taken public “probably two years too soon”.

“…the dossier that Tyratech went to market with was really not, I know now, it was not credible,” the former employee told us.

They also told us that after the investors exited from TyraTech, they “moved TyraTech away from Florida…just to get away from [Dr. John Scott and the investor group].”

Self-Enrichment Without Even Having a Product: PureCycle’s Executives Received $7 Million in Cash Bonuses Simply For Closing the SPAC Deal

The Executives Are Slated to Receive ~$40 Million in Compensation, Before Generating A Single Penny of Revenue

PureCycle’s executive team members seem to have done well for themselves over the years despite the repeated destruction of public shareholder capital. This might be because the team knows how to position itself to cash out regardless of how things turn out for investors.

Typically, executives who believe in their business are compensated for key sales, profitability, or stock performance milestones. PureCycle’s CEO and CFO took cash off the table immediately, respectively collecting $5 million and $2 million in bonuses simply for closing PureCycle’s SPAC deal. [Pg. 122, Pg. 2]

These lucrative cash bonuses don’t include base salaries for the CEO/CFO/CCO, collectively totaling $1.54 million per year. Nor do they include CFO Michael Dee’s 1.2 million in share grants (worth ~$30 million as of this writing) that begin vesting in 6 months until the date a plant is ever deemed operational.

Part II: PureCycle’s “Breakthrough” Technology

PureCycle is the latest member of a parade of “revolutionary” companies taken public by its executive team, which has been marred by repeated failure.

The company licensed its technology from major plastics producer Procter & Gamble (P&G) in October 2015, roughly around the inception of the company. [Pg. 69] P&G had developed the technology because PP was the largest plastic type used by the company, and it has been notoriously difficult to recycle, according to an interview with John Layman, the senior scientist at P&G who developed the technology.

One might wonder: if the technology was a major breakthrough, as described in the company’s presentation, [Pg. 43] why P&G didn’t license it to a chemical company like Dow or well-established plastics or polycarbon companies rather than a team with a history of repeated failures and no specific polycarbon expertise? Or, why not develop the technology internally as a new income stream?

P&G’s Layman was asked this question in a written Q&A. He explained that a Global Business Development Director at P&G had a personal relationship with the team at PureCycle’s parent company, Innventure, and made the connection. In fact, that same P&G executive had been working with the Innventure predecessor team (XL Tech) since at least 2005 to promote P&G’s fledgling technology and ideas to universities and outside companies.

The P&G employee that bridged the deal appears to have later taken a senior position at PureCycle, now serving as VP of Commercial and Business Development.

Our analysis leads us to believe that P&G likely had a “technology” that it saw no economic sense in commercializing itself, so it spun it off, providing a steady stream of positive PR for the plastic producing giant, showcasing its efforts to promote recycling.

Key Hurdle: Identifying Enough High-Quality Feedstock to Run the Process Economically

Scott Saunders, General Manager Of KW Plastics And Former Chairman Of the Association Of Plastics Recyclers, Described the Market For Feedstock as “Very Competitive”

One of the key challenges (and likely future bottlenecks) of PureCycle’s proposed process is in securing enough quality feedstock to make the process economical.

In a November 2020 interview, Procter & Gamble’s inventor of the technology was asked about potential bottlenecks of PCT’s process. He answered by raising the issue of feedstock availability:

“I think the fact that you have to ensure you have feedstock coming in and I think that’ll be a bottleneck is ensuring the feedstock is of the right quality, at the right quantity, to keep the larger plants running.”

“I believe some of the bigger risks with the larger scale will be ensuring that we have the feedstock and that feedstock is consistent per our partners’ agreement”.

PureCycle’s go-public prospectus also acknowledged this as a key risk factor more than once, stating:

“PCT’s failure to secure waste polypropylene could have a negative impact on PCT’s business, financial condition, results of operations and prospects.” [Pg. 28]

“PCT may not be successful in finding future strategic partners for continuing development of additional offtake and feedstock opportunities.”

We reached out to Scott Saunders, general manager of KW Plastics and former Chairman of the Board of the Association of Plastics Recyclers, to gain more insight on PureCycle’s role in the market. We asked Saunders, who has 30 years’ experience in the business, about the availability of PP feedstock. He told us:

“We pay for it and it’s a very competitive worldwide market. There´s more buyers for the scrap material today than there is material available.”

Saunders: “There’s Not Enough Non-Contaminated PP Scrap To Support These Processes”

We asked Saunders about PureCycle’s claims, process and ability to source the PP necessary to run its process at peak efficiency. He told us:

“The problem I see with chemical recycling – and I´m not an expert in this process but I am an expert in PP raw materials – there is not enough non-contaminated PP scrap to support these processes. So you´re going to get a wide range of materials that have varying degrees of other resin contamination.”

In his previously referenced interview, P&G’s Layman brought up contamination and said the contamination the company was currently removing during processing was “fairly low” and “less than 5%”.

Saunders replied to us that this low level of contamination in scrap PP simply doesn’t exist in volume:

“And what´s stated publicly by PureCycle themselves is that the facility works well up to 5 percent contamination. I´ve been buying PP scrap for 30 years and I´m not aware of any PP scrap in volume that has any less than 5% contamination in the world.”

Saunders estimated the average levels of contamination in post-consumer PP were between 20%-25% including residues in the container, paper labels, glue and other elements.

Richard Minges, 10 Year Executive for Custom Polymers: “It’s More About The Raw Materials That Can Be Secured”

We also spoke to Richard Minges of Custom Polymers, Inc., to better understand the PP market. Minges has worked in sales and business development for Custom Polymers for 10 years. He also stressed that competition for feedstock revolved around what was available:

“We could be competing on some raw materials. I think there will always be a need for mechanical recycling and the chemical side is still proving out. There may be a certain level of competition but it´s more about the raw materials that can be secured.”

…

“There´s a huge demand for post-consumer natural PP…a lot of the packaging companies are wanting post-consumer materials to get back into their packaging so they can tell a marketing story. “

Saunders: “I Don’t’ Know A Single [Buyer] That Would Pay” PureCycle’s Claimed Premium In Bulk

Saunders, when asked, also cast doubt on PureCycle’s ability to sell its “virgin-like” end product at the price it projects. [Pg. 23] He told us:

“They´re also stating that they´re going to sell their resin for as much as $2 a pound, which is a huge premium. And the people that we have that are paying premium right now is because they only need a small amount and it´s a marketing ploy and they want it secured. And if I go back to these same people and tell them I have a 10x as much and the price is going up to $2 then I don´t know a single one who would pay.”

Saunders: “At This Point, We’re Not Very Worried” About PureCycle

When talking about PureCycle’s potential competitive advantages and what they’ve been able to achieve at a lab scale, Saunders told us he was “not very worried” about PureCycle disrupting the industry and cast doubt on its potential to scale. He told us:

“We can do great things in the lab ourselves. We have all types of equipment that have worked great in the lab and we´ve never put them in service. But hey they´re really smart people and have a lot of guys there who know how to talk to Wall Street so we´ll see what happens. At this point we´re not very worried”.

He drew the same common-sense conclusion we arrived at about P&G licensing out its technology:

“This technology was developed by Procter and Gamble, one of the most fiercely competitive companies ever created and we have to believe all of a sudden the P&G company has figured out how to break down chemically PP. That would give them a huge competitive advantage over Unilever and all the other competitors in the worldwide consumer products field, and they´re so generous they´re going to give that away”.

Ajit Perera, VP of Post-Consumer Operations at Talco Plastics: “Most margins are generally single digit. We´d be popping champagne if we had 10%.”

We wanted to find out whether Purecycle´s forecasts of more than 45%-59% percent EBTIDA margins sounded credible to executives who had been recycling plastics for decades.

Ajit Perera, the vice president of post-consumer operations at Talco Plastics in California, like Saunders, insisted that the business was “high volume, lower margin”. He said:

“Until recently in the post-consumer mechanical recycling we would have been happier than hell if we had a two-digit margin. Most margins are generally single digit margins. We would have been popping champagne here if we had a 10% margin.”

Perera readily admitted he was no expert in chemical recycling but accepted there was buzz in the market about claims being made and the potential to take even post-industrial PP scrap and convert it to virgin-like monomer through a chemical process.

But he said undoubtedly chemical recycling was much more costly than the hype would suggest:

“The common man does not know that you can´t mix plastics. You can´t take (recycled) PE and PS and PP mix it and make a product. At that point its garbage…And then if you have colors, if its red then it has to stay red or go black, or a shade of red like orange or purple. But when you take it back (with chemical recycling) to a monomer, you can remove all that and take it back to a virgin plastic. To do that, it costs a lot of money and your carbon footprint is huge.”

Often, Breakthrough Intellectual Property is Cited by Other Patents or Peer-Reviewed Journals. We Found Nothing Citing PureCycle’s Technology

Many leading plastics companies publish peer reviewed studies that detail their advancements in the field. Contrary to that practice, we were unable to find a single peer reviewed study in any scholarly journal citing PureCycle’s licensed process.

Breakthrough patents are also regularly cited by other companies or publications that reference those discoveries in their own findings. The only citations we found for PureCycle’s licensed patents were by its own authors.

We e-mailed John Layman of P&G to inquire as to whether or not he could point us to any scholarly journal articles involving PureCycle’s technology and have not heard back as of the time of this writing. We also submitted a similar inquiry through PureCycle’s contact form on its website and have not heard back as of this writing.

PureCycle’s Licensed Patents Seem to Rely Heavily On Prior Discoveries That Never Ended Up Reaching Commercial Scale

Despite claims of discovering a “breakthrough”, PureCycle’s licensed IP isn’t based on a new concept.

For example, a 1993 patent specifically covers similar methods used by PureCycle, such as varying temperatures or pressures of butane and propane in order to reclaim PP.

We consulted with a 30-year expert on polymers, with a background in advanced plastics recycling. He found the plastic solubility issues to be interesting, but not new, and described the use of a PureCycle’s process on unknown composition feed stock as “insane”.

“The fact that PE, PP, PET, etc. are truly soluble in hydrocarbons at elevated temperatures and elevated pressures is really cool stuff. The fact that you can vary the temperature and pressure to selectively solubilize different compounds is incredible. Performing this on a large scale with known feed stock materials is extremely high risk. Performing this process on unknown composition feed stock to extract plastic is insane.”

30 Year Expert In Polymers: The Company’s “Indirect” And “Vague” Patent Is A “Regurgitation Of Prior Art”

The expert we consulted reviewed PureCycle’s technology portfolio and noted clear deficiencies:

“There isn’t much technical information or supportive data/results from any testing. There is no mention of the needed actual testing of the final product. It is indirect and vague. The hazards are clearly minimized, which is typical when serious hazards are expected and read by someone without any prior knowledge or experience.”

Our chemist concluded by noting that PureCycle’s technology didn’t appear significantly differentiated and had left out key metrics for determining economic viability:

“While the n-butane & propane blends for solvent, heated and pressurized may extract a slightly higher concentration of PP per cycle pass than carbon dioxide and n-butane, it is still apparently very low. PureCycle doesn’t disclose what these values are in the scaled-up testing.”

He concluded:

“The permitting, engineering, and equipment would be very expensive and a challenge full scale. The plastic recovered may or may not be accepted or usable. I don’t think the process could ever be cost efficient. The process is expensive, the test requirements and documentation is extensive, and the value of the product just isn’t high enough.”

Expert: Solvents Used In PCT’s Process Are “Extremely Flammable Gasses” Held Under High Pressure, (i.e. a “Bomb”), With Obvious Major Safety Implications

Our chemist also highlighted the flammable nature of PureCycle’s process, telling us “the flammability and hazards of this process cannot be understated” and that “as for the solvents in the PureCycle process being listed as n-butane and propane, both are extremely flammable gases.” He continued:

“Taking propane and butane, heating them in a vessel to a couple hundred degrees and holding it under pressure at thousands of pounds per square inch, is a bomb. The integrity of all of the vessels and equipment must be flawless and maintained to be flawless. The specifications for equipment to do this is extreme and rightfully so. Any incident would be catastrophic.”

The Company Has Unresolved Issues At a Lab Stage, Yet Is Trying To Scale Anyway. The Technology Doesn’t Seem Ready, Which Pose Both Economic And Safety Issues

Scaling a chemical process, especially one with variable feedstock, often presents new problems that would not be encountered at a lab/pilot scale. That’s why, processes are usually perfected at a lab scale before scaling up.

It appears as though PureCycle is still having problems at a lab scale, but is scaling up anyway.

In the same November 2020 interview, P&G’s scientist who developed the technology disclosed there had already been issues with “clogging”:

“Now, when it comes to scaling, I would just say issues or I would more likely frame those as typical growing pains of any technology or process, first of all, we transitioned from batch at Phasex to continuous at the FEU. There were always some learnings there. We had, I would say, idiosyncrasies of the technology present themselves of the equipment. We had clogging from time to time where polypropylene would not behave.”

In an email request for information, neither the inventor of the process nor a P&G spokesman would clarify if the clogging issue had been resolved yet.

Our chemist dismissed the notion that such issues were passed off as “typical learnings”:

“This was a (poor deflection) response in my opinion to a good question…100% of the ‘bugs’ should be understood and resolved on bench top/lab experiments before scale-up. ‘Learning’ basic known properties at a large scale with a bomb typically doesn’t come out well. People get killed.”

PureCycle Hopes to Help Solve Its Feedstock Woes By Licensing Feedstock Technology From A Tiny UK Company With a Small Pilot Plant

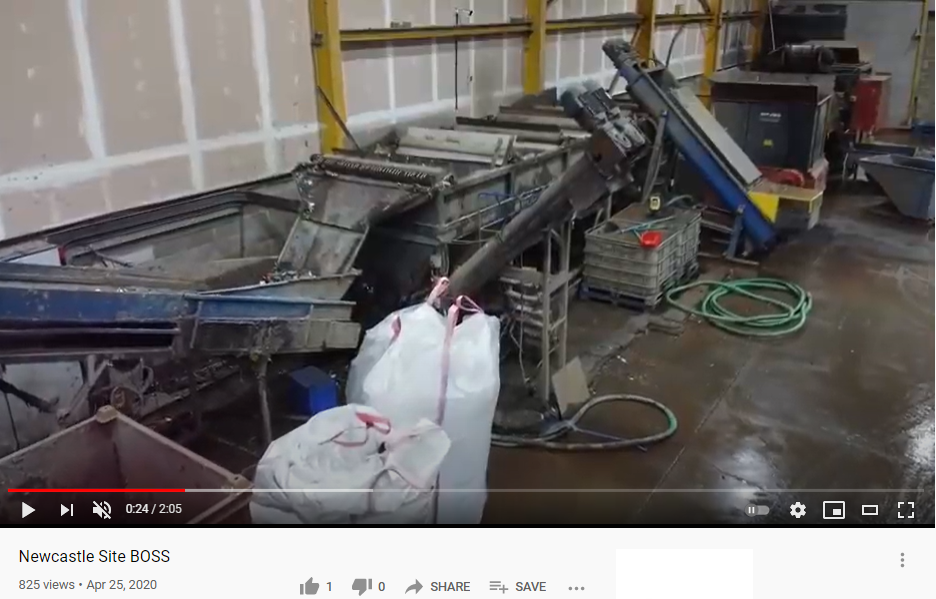

A proposed solution to the feedstock problem, based on PureCycle’s filings, is an agreement signed in November 2019 with a small startup in the UK called Impact Recycling Limited, to license a process for developing feedstock.

Impact Recycling’s only current operational plant is an amateurish-looking setup consisting of a few dusty looking machines connected in series and housed in a small warehouse, according to a video the company posted last April.

The company has a patented technique for separating polymers by a method of “shuggling,” which in its own patent it describes as simply “shaking”.

“The present applicants have surprisingly discovered that shuggling the mix using a centrally located oscillating baffle causes separation. Shuggling may be considered as a form of agitation, though it is distinct in that it does not include stirring which is typical of agitation. Shuggling may be considered as shaking.”

Shaken not stirred. One wonders whether all the leading polymer scientists in the past 50 years didn’t think to try that.

When asked exactly what the technique of “shuggling” was, even Impact Recycling CEO David Walsh seemed confused:

“Yeah I don´t know what that is either. I just came across it in an old video. No, we´re just creating whirlpools in water and the whirlpools then separate the two different types of plastic.”

He clarified that the recycled PP was being sold for industrial uses and not the higher-value consumer and food-grade applications.

In the four years since Impact Recycling filed its patent, the company completed construction on its first pilot plant—a small 6,000-ton capacity pilot plant in Newcastle, UK—in Q2 2018, according to Impact Recycling’s website. In September 2020, Impact Recycling announced plans for a second trial plant. Work on that, however, has not yet begun. And funding for a 25,000 ton per year demonstration plant in Holland has so far proven elusive, CEO Walsh told us.

Like the P&G patent that PureCycle licenses, we found no other authors besides Impact Recycling that reference or cite its patents, suggesting “shuggling” may not be the technological breakthrough in feedstock PureCycle is hoping for.

PureCycle’s Key Partnerships: Lessons in Greenwashing

One of the key arguments for bulls is that PureCycle has agreements with well-known companies like L’Oréal and Total. Surely such large corporations must have done extensive vetting in order to sign something with an early-stage unproven plastics company?

The reality of the plastics industry is that many large producers regularly look to announce recycling partnerships to show they are trying to “do something” about the problem they have created.

Just last October, we published a report exposing major issues with plastics recycling company Loop Industries Inc., which had also signed agreements with L’Oréal, along with others like Pepsi, and Coca-Cola (which cancelled its agreement shortly after our report).

Contrary to what PureCycle and its bankers claim, these partnerships do not generally signal deep due diligence from the companies involved.

Such off-take agreements typically specify that these companies have the right, but not the obligation to purchase recycled plastics. They are an option that pose virtually no risk to the counterparty while making for a positive news release.

Conclusion: Yet Another ESG SPAC Gone Wrong

Wall Street will exploit any loophole it can find.

We think PureCycle represents the worst qualities of the SPAC boom; it’s another quintessential example of how executives and SPAC sponsors will enrich themselves while hoisting unproven technology and ridiculous projections onto the public markets, leaving retail investors to face the consequences.

We commend the House Financial Services Committee for examining SPAC listings in its forthcoming May 24th hearing. We encourage a closer look at:

- Excessive cash and unrestricted stock compensation to management teams and SPAC sponsors, allowing them to regularly cash out hundreds of millions before ever even generating a revenue or executing on their plans. There should be ‘skin in the game’.

- Implementing “quiet period” rules in order to prevent deal sponsors from unduly influencing brand new listings, similar to rules for traditional IPOs.

Disclosure: We are short shares of PureCycle Technologies, Inc. (NASDAQ:PCT)

Legal Disclaimer

Use of Hindenburg Research’s research is at your own risk. In no event should Hindenburg Research or any affiliated party be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information in this report. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities covered herein. You should assume that as of the publication date of any short-biased report or letter, Hindenburg Research (possibly along with or through our members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or consultants) along with our clients and/or investors has a short position in all stocks (and/or options of the stock) covered herein, and therefore stands to realize significant gains in the event that the price of any stock covered herein declines. Following publication of any report or letter, we intend to continue transacting in the securities covered herein, and we may be long, short, or neutral at any time hereafter regardless of our initial recommendation, conclusions, or opinions. This is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. Hindenburg Research is not registered as an investment advisor in the United States or have similar registration in any other jurisdiction. To the best of our ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the stock covered herein or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Hindenburg Research makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Hindenburg Research does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein.

[1] This commercial scale portion of its Ironton plant has been referred to by the company as Phase II.

6 thoughts on “PureCycle: The Latest Zero-Revenue ESG SPAC Charade, Sponsored By The Worst Of Wall Street”

Comments are closed.

Hey shorty, the more you short the more I buy. I’ll be moving my 200 shares to a cash account and setting a high limit sale price. You’ve been warned.

P.S. Buy my active ETF

Other than being pissed off, I don’t have much to say. I bought yesterday at $24 and change and quick;y lost 40%

I am done buying spacs and selling a couple I own.

Thanks for the information. It is distressing to learn after my conversation two weeks ago with CEO

Mike Otworth was so pleasant but then why shouldn’t they be, salesmen are always agreeable.

I find it amazing that these investment banks can legally issue buy/sell “analyst” recommendations for companies in which they have very large ownership stakes. And those stakes weren’t even disclosed, at least not in my brokerage’s news feed entries for PCT. Seems to be both deceptive and a blatant conflict of interest.

If some two bit charlatan did the same thing, they’d call it an illegal “pump and dump” scam. But in the USA laws are for little people, not investment banks.

Another great article by Hindenburg, there’s no end to the scams out there.

These SPACs reek of the reverse merger scams from the mid 2000s. Thanks for the info