(NASDAQ:LOOP)

- Loop Industries has never generated revenue, yet calls itself a technology innovator with a “proven” solution that is “leading the sustainable plastic revolution”. Our research indicates that Loop is smoke and mirrors with no viable technology.

- As part of our investigation, we interviewed former employees, competitors, industry experts, and company partners. We also reviewed extensive company documentation and litigation records.

- Former employees revealed that Loop operated two labs: one reserved for the company’s two twenty-something lead scientist brothers and their father, where incredible results were achieved, and a separate lab where rank-and-file employees were unable to replicate the supposedly breakthrough results.

- The two brothers who act as lead scientists for Loop and who co-invented Loop’s recycling process appear to have no post-graduate education in chemistry and list no work experience other than Loop.

- A former Loop employee told us that Loop’s scientists, under pressure from CEO Daniel Solomita, were tacitly encouraged to lie about the results of the company’s process internally. We have obtained internal documents and photographs to support their claims.

- Loop focuses on recycling a common form of plastic called “PET”. According to a former employee, Loop’s previous claims of breaking PET down to its base chemicals at a recovery rate of 100% were “technically and industrially impossible”. The same employee told us the company’s claims of producing “industrial grade purity” base chemicals from PET were false.

- According to litigation records, Loop’s CEO, Daniel Solomita hired a convict, who had previously pled guilty to stock manipulation, to help raise Loop’s startup capital. That convict introduced Solomita to another convict who facilitated Loop’s first investment.

- Solomita has no apparent formal science education but has a history of stock promotion at another publicly traded company that subsequently imploded.

- Executives from a division of key partner Thyssenkrupp, who Loop entered into a “global alliance agreement” with in December 2018, told us their partnership is on “indefinite” hold and that Loop “underestimated” both costs and complexities of its process.

- We contacted Loop’s other partners, including Coca-Cola and PepsiCo, most of whom refused to divulge whether any plastic had been recycled as part of their partnerships with Loop. Comments from Danone, owner of the Evian brand, suggested it had not bought any PET from Loop thus far. We suspect these partnerships have gone nowhere.

- Loop’s JV with PET and chemical company Indorama, promoted frequently over the last two years as an imminent revenue stream, is “still being finalized”, according to an employee, despite being announced in 2018. An Indorama employee told us no production has taken place thus far.

- We expect Loop will never generate any meaningful revenue. With a market cap of ~$515 million, we see 100% downside to Loop once it burns through its ~$48 million in balance sheet cash.

- We have submitted our findings to regulators.

Initial Disclosure: After extensive research, we have taken a short position in shares of Loop Industries. For members of the media who wish to independently corroborate our work please contact us for introductions to whistleblowers and other sources on condition that their anonymity is maintained unless they explicitly agree to go on-record. This report represents our opinion, and we encourage every reader to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report.

Background: The Biggest Problem and the Biggest Opportunity in Plastics Recycling

Every year, about 27 million tons of plastic waste winds up in landfills, creating a major problem for the environment as well as for the plastic industry.

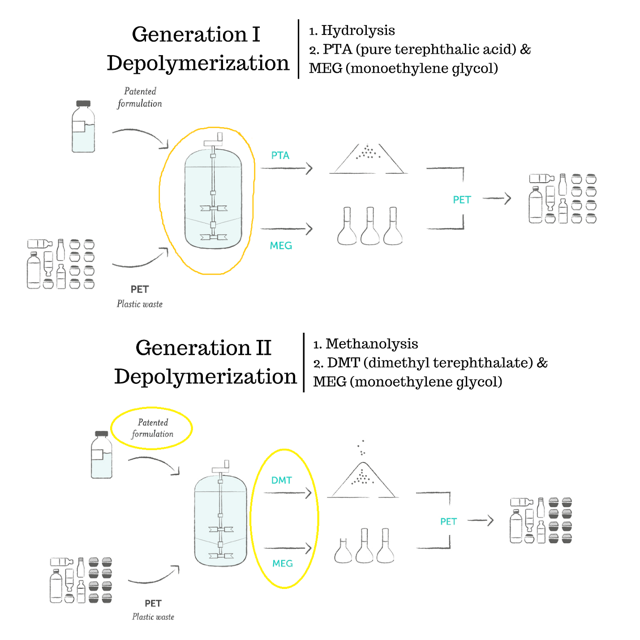

Low-cost recycling is the answer to these problems and the biggest challenge in the recycling industry has been PET plastic – the cheap, clear, lightweight plastic often used in drink bottles and other food and beverage packaging.

Traditional PET recycling methods require heat and pressure to break down and re-shape plastic, which is costly. New “advanced recycling” techniques aim to minimize the use of heat and pressure by breaking down plastic with chemicals, but thus far these methods have proven expensive and inefficient.

There are an estimated 70 million metric tons of PET plastic generated annually, representing a massive global problem and, conversely, a major opportunity for whoever can solve the problem. [Pg. 8]

Enter Loop Industries, Which Has Essentially Claimed to Have Found the Holy Grail of Plastics Recycling—An Inexpensive, Efficient, Profitable Process For Recycling The World’s Most Ubiquitous Plastic

Loop Industries (NASDAQ:LOOP), headquartered in Quebec, claims to have found the answer.

Loop refers to itself as a technology company whose “mission is to accelerate the world’s shift toward sustainable PET plastic and polyester fiber and away from our dependence on fossil fuels.”

The company was incorporated in Nevada on October 23, 2014 and went public through a reverse merger in June 2015. [Pg. 8]

Loop has claimed to have developed a patented and proprietary technology that breaks down PET plastic:

“of any color, transparency or condition, including waste PET plastic recovered from the ocean that has been degraded by the sun and salt, to its base building blocks (monomers)” [Pg. 6]

Even more incredibly, the company claims to have achieved these breakthroughs after setting up a laboratory using “products purchased from the local hardware store” [translated from French][1].

In its most recent October 2020 investor presentation, Loop calls its process “proven” and says that its facilities are expected to have a “margin profile which notably exceeds competing recycling technologies, with EBITDA margins >40%.” [Pg. 3] Its website, as of October 11, 2020, says that Loop is “radically transforming how plastic is produced”.

In other words, the company claims to have discovered how to turn worthless trash into pure gold, a feat that multi-billion chemical companies such as DuPont, Dow Chemical, and 3M have been unable to achieve on a large scale despite years of efforts.

Loop’s investor base has been encouraged by both its breakthrough claims and a slew of partnerships that have lent credence to its technology. These partnerships include some of the biggest firms that generate plastic waste worldwide: Coca-Cola, PepsiCo and Danone to name a few.

Reality Check: Former Employees, Plastics Experts and Competitors Blow The Whistle On “Liar” Scientists, Faked Results, Rudimentary Technology And Hollow Partnerships

As we will show, Loop’s claimed breakthroughs in PET plastic recycling are fiction. Our investigation into Loop, spanning 6 months, has included speaking with multiple former employees, company partners, polymer/plastic experts, and competitors.

Our investigation points to one conclusion: in the words of a former Loop employee, we simply “don’t really think they have the technology”.

Former employees painted a picture of a chaotic company, whose lead scientists are twenty-something “liars”, with no relevant work experience other than Loop, that were able to achieve “impossible” results in a secret second lab that rank-and-file employees weren’t allowed to access.

Loop’s supposed proprietary process is a black box that has not shown itself to be more efficient or cost effective than comparable solutions, contrary to the company’s claims, according to former employees and outside experts.

Loop’s CEO, who has no specific educational background in chemistry, sought out the help of several convicts to put together Loop’s startup capital, according to litigation records. Loop’s management has a track record of taking investors on a ride with sweet sounding public company stories that have ended in catastrophic losses.

Loop’s partnerships have gone almost nowhere. The company announced a key joint venture in 2018 to build a facility with well-respected PET and chemical company Indorama, but two years later the terms of the deal have yet to even be finalized. Other major consumer plastic brands were unable to confirm to us that their partnerships with Loop had progressed.

Experts we spoke with raised serious questions about the company’s ability to make its “unparalleled purity” end product, as claimed, at large scales with any cost efficiency. They said Loop is focused on a decades-old problem and there is nothing new or revolutionary about the idea of breaking down PET in the fashion Loop is claiming.

All told, we think Loop is just a smoke-and-mirror show masquerading as a technological leader.

Part I: Background on Loop’s Key People

Loop’s CEO Daniel Solomita: No Educational Background In Chemistry and A History of Stock Promotion

Some of the largest chemical companies in the world are working with their teams of top scientists to solve the plastic sustainability problem.

Major multi-billion dollar corporations like Dow, DuPont and Eastman Chemical have committed to deploying their combined teams of tens of thousands of employees to help create a circular economy for plastic and waste. [1,2,3]

Given Loop’s claimed breakthroughs, one might similarly expect top scientists at the helm. Instead, we found that Daniel Solomita, Loop’s CEO, has no apparent formal education in chemistry or polymers.

Solomita’s education, according to his LinkedIn and SEC biography includes 2 years studying Finance at Dawson College and 1 year studying computer science at Concordia University. He also cites attendance at an MIT management program during his tenure at Loop.

His LinkedIn does not include any science or chemistry-related work experience, other than Loop, but for 4 years he spent doing “Business developpment [sic]” at SMH Recycling.

In Solomita’s official SEC biography he lists being a director and President of Dragon Polymers – a “recycler of industrial polymers through landfill remediation” that focused on PET – in April 2012 [also see: Pg.20].

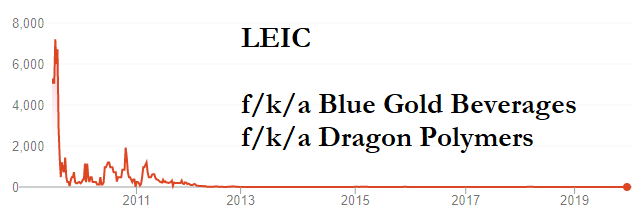

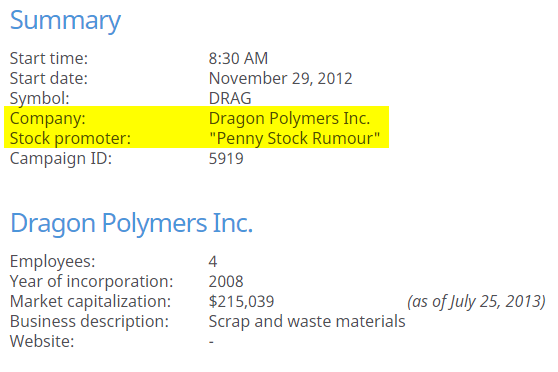

The former stock of Dragon is now listed as a “shell” on OTC Markets and trades 99.9% off its highs. [Pg.2] The spikes at the beginning of the stock chart show portions of Solomita’s tenure at Dragon, which had previously been named Blue Gold Beverages.

Both Blue Gold and Dragon Polymers were pushed by stock promoters like xplosivestocks.com and outlets like “Penny Stock Rumor”.

According to Dragon Polymers’ 2014 annual report [Pg. 12], the company changed its name on October 12, 2014 and impaired its recycling assets because it had “no hopes of future revenue from the recycling operations.” [2]

Two weeks later, on October 23, 2014, Solomita incorporated Loop Holdings. [Pg. 13]

It seems Loop was born out of the business concept that Solomita’s former company impaired to $0.

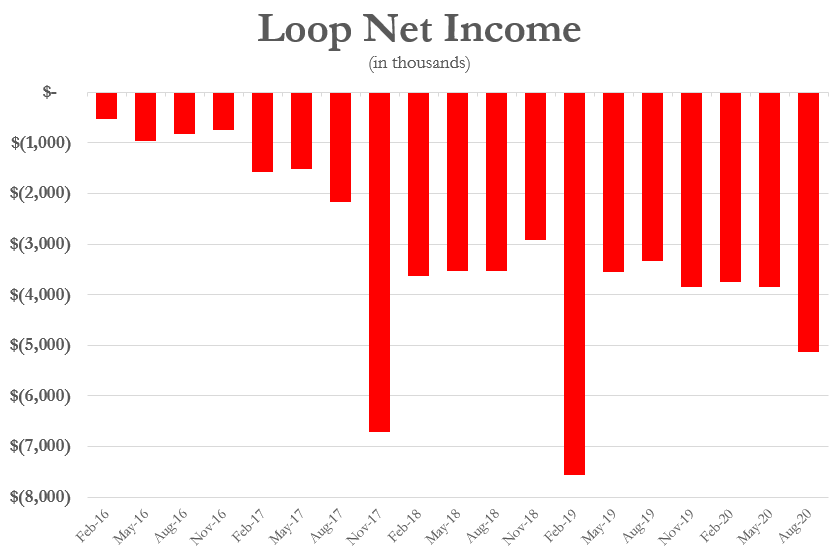

Considering this, it doesn’t come as a surprise to us that Loop has never turned a profit, never generated a single dollar in revenue, and has never generated any cash from operations.

Loop’s Origins: CEO Solomita Engaged a Convict Who Pled Guilty to Securities Fraud to Help Raise Loop’s Early Capital

That Convict Introduced Solomita to Another Convict (Who Had Pled Guilty to Wire Fraud and Securities Fraud) Who Helped Facilitate the Company’s First $80,000 Investment

One might think that a company with breakthrough technology in plastic recycling would have attracted major chemical companies or well-known VC firms as early investors. Firms like Eastman Chemical, Kleiner Perkins, and Blackrock are all actively involved in plastics recycling.

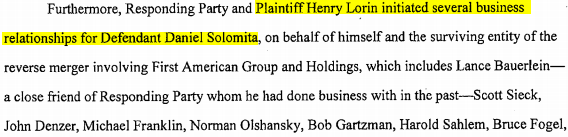

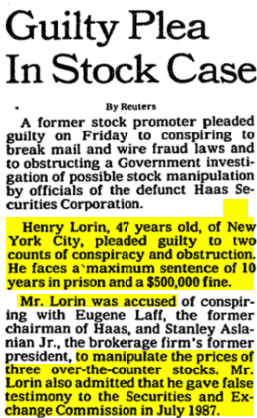

Instead, according to a lawsuit filed in 2017 in the Superior Court of California (Case No. BC648640), Loop turned to an individual previously convicted of securities fraud, Henry Lorin, to help raise its early outside capital.

The lawsuit against Loop and Solomita was filed by Lorin, who had “initiated several business relationships” for Solomita, according to the exhibits. Lorin previously “pled guilty in the Southern District of New York to conspiring to manipulate the prices” of certain securities and was found to have given false testimony to the Securities and Exchange Commission.

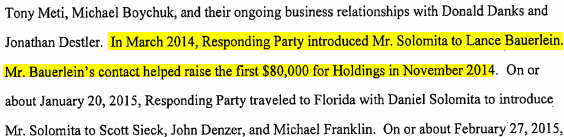

The same documents state that Lorin introduced Solomita to another individual, Lance Bauerlein, who helped raise the first $80,000 for Loop.

Bauerlein was indicted criminally in June 2013 and later pleaded guilty to wire fraud and securities fraud in 2015. He was also charged by the SEC over agreeing to “engage in manipulative and deceptive securities transactions”.

Bauerlein was also barred by the NASD and fined $90,000 and ordered to disgorge $280,000 decades earlier for engaging in “private securities transactions at unfair prices”.

Loop Co-Founder Donald Danks Has A History Of Allegations Of “Misleading Statements”, “Unlawful Business Practices”, and Leaking Material Non-Public Information

Loop’s co-founder Donald Danks, who reportedly helped Solomita start Loop in 2014, has a checkered past of his own.

Danks previously served as Chairman and CEO of iMergent.

According to a 2007 article in the Brisbane Times, iMergent was subject to a slew of allegations of misleading statements, unlawful business practices, violations of the Business Opportunity Fraud act and wrongfully enticing customers.

On top of those allegations, Danks was accused by Barron’s of leaking material non-public information about his company’s revenue numbers.

Danks served as a Director of Loop from June 29, 2015, until June 28, 2018. He continues to actively promote Loop on social media, re-tweeting Loop tweets as recently as September 2020 and a reposting a LinkedIn post in August 2020.

Loop’s Current Process Was Invented By Two Brothers in Their Twenties With No Work Experience Other Than Loop And No Post-Graduate Education In Chemistry or Polymers

One might consider a CEO with a history of stock promotion and an early association with multiple individuals convicted of securities-related fraud to be a red flag.

But putting that aside for the moment, it isn’t completely impossible for an unlikely/unsavory cast of characters to somehow attract a scientist that manages to identify new breakthroughs.

So, who is the talent behind the process that Loop claims could help reshape the multi-billion dollar plastics industry?

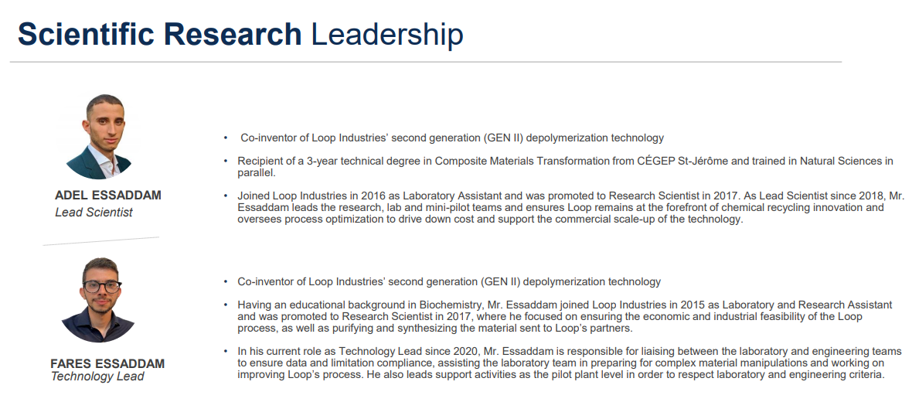

The company’s current (Generation II) process was invented and patented by two brothers in their 20s, Adel and Fares Essaddam, who have no apparent post-graduate studies in chemistry or polymers or any work experience other than Loop. Adel started at Loop just months after completing his diploma and Fares started working for Loop while still attending university.

Adel is Loop’s “Lead Scientist”, according to the company’s October 2020 investor presentation. According to Adel’s LinkedIn page, he has a technical diploma in composite materials transformation from CEGEP de Saint Jérôme and has no other work experience aside from Loop. He finished his education in 2015 and started at Loop in January 2016, according to his LinkedIn.

Adel’s brother Fares is the company’s “Technology Lead”. Fares also lists no other work experience on his LinkedIn page other than Loop. His education at Universite d’Ottawa took place between 2014 and 2018 and he started as an analyst at Loop in May 2015, working at the company for 3 years while in school, according to the LinkedIn bio.

Their dad’s patent formed the basis of the company’s GEN I process, which has now become defunct in favor of the company’s new GEN II process.[3] [Pg. 8]

When we asked a former employee about the Essaddam brothers and how their process was perceived by others at Loop, we were told:

“They learned most of the stuff from the dad and they were lying the same way as the dad. They wanted to make sure to get results.”

Part II: Former Employees Speak Out

Former Loop Employee: “The Chemists Behind the Technology Are Liars”

Former Loop Employee: “I’ve Seen False Numbers. I’ve Seen ‘I Want This Sample, Give Me This Result. I Don’t Want To See Anything Else. I Want To See This Result’.”

After speaking to former Loop employees, we believe we understand the dysfunctional dynamics at play within the company.

When asked how it was possible that the chemists and experts we interviewed (whose opinions are detailed later in this report) didn’t see a way for Loop’s process to be cost efficient, but that Loop did, they told us:

“The main problem was that the chemists behind [Solomita’s] technology are liars. They made him hear what he wanted to hear…I was working on the purification of the MEG and I was not successful at all. I worked on that for [redacted] and it was a painful recovery because some of the dyes were staying in the MEG (PET base chemical monoethylene glycol) and there was no way to remove them. I tried many, many things and I was not successful at all.”

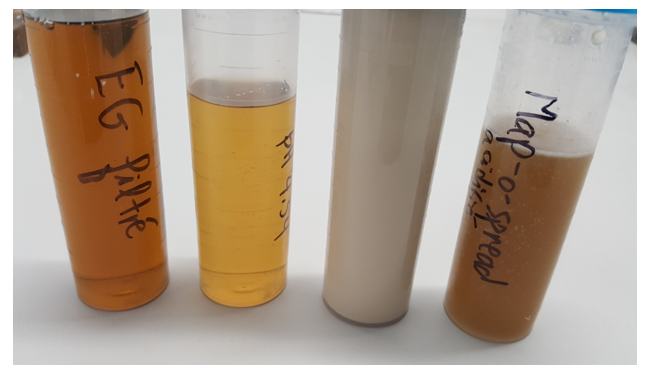

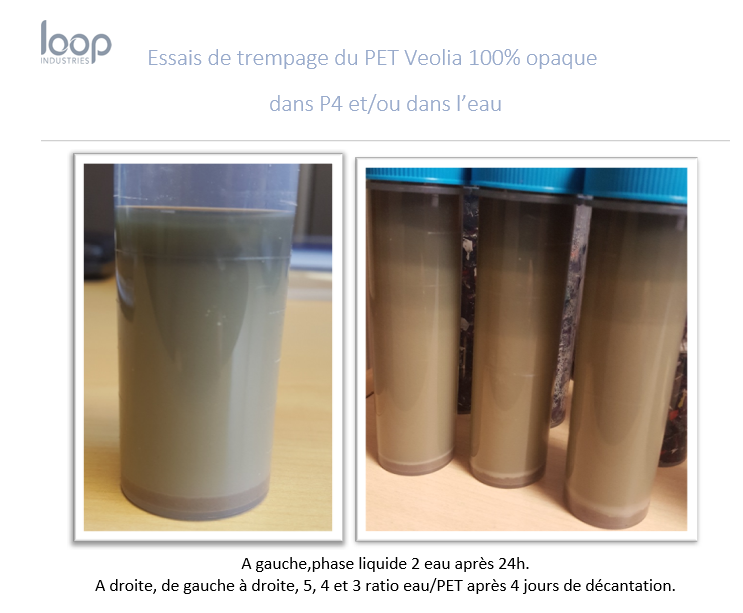

A former employee provided us with these photographs of the dirty MEG:

When we asked how Loop dealt with the difficulties of proving their process internally, they told us they had seen false numbers being used internally:

“I’ve seen false numbers… I’ve seen ‘I want this sample… Give me this result. I don’t want to see anything else; I want to see this result.’”

The employee described an intimidating tone at the top, referring to CEO Daniel Solomita:

“If you don’t do what he expects you to do, not fast enough, or if the results are not good enough, he gets angry and he can yell at you for hours and hours and hours. Yeah. I’ve seen one of his worst frustrations, he yelled at two people for three hours, non-stop.”

When asked about Solomita and whether he would demand certain results, a second employee told us:

“There’s just facts and there’s chemistry and there’s certain things you can’t like – even if you want something to happen, you’re not going to get a resolution. It has to come from a scientific point of view in order to find resolution. You can’t just throw money at it, or just have a fit or something. You can’t direct the molecules to behave the way you want them to like you would, for an example, an employee showing bad behavior.”

Two Former Loop Employees: The Company Has Two Labs. One For The Essaddam Family And One For “All The Other People”.

Former Employee: “When It Was Time to Talk About Results, They Were Hiding Things And Bypassing Us To Go Present Results To The Boss”

Based on what we were told by former employees, it seems like the ‘miracle’ results and successes that were being produced at Loop came out of a separate lab for the Essaddam family that had been sequestered from other Loop employees.

Two former employees confirmed the existence of separate labs to us. The first said:

“When I was there, there was two labs. One of them was for the Essaddam family. And one of them other was for all the other people. We would not see what they were doing. It was in the same building; it was one on the second floor and one on the first floor. We could go into the lab but at some point, it was dangerous because they had an explosion in their lab from toxic fumes since they were doing so many crazy things in there. We would never go in there. I was trying to avoid it as much as possible.”

The first also told us about suspicious results that were coming out of the Essaddams’ lab and how the family separated themselves from the rest of the company’s scientists:

“They were friendly but at some point, when it was time to talk about results, they were hiding things and bypassing us to go present results to the boss. So, they would present their results and not ours. They had two faces. They had their father in the background for everything so they would discuss everything as a family. I’m sure like every day they would probably discuss that at the family dinner. I have a couple of other friends that left because they couldn’t stand it anymore.”

“There was always a group saying ‘they did this again…’ ‘They brought samples and wouldn’t tell them what it was’ and ‘when we gave results, they weren’t happy about it…’”

Solomita Claimed the Process Needed to Remain Secret—Even Within the Company—to Avoid Leaking it to Competitors

The second former employee confirmed that the father and two sons worked in an R&D lab while the other employees worked in a second lab, which analyzed samples received from the R&D lab.

“One of them was more like the analytical lab, which then needed to test the results. And then the actual R&D and process was more from the other lab. The one with the gentleman and the two boys [Essaddam and his sons].”

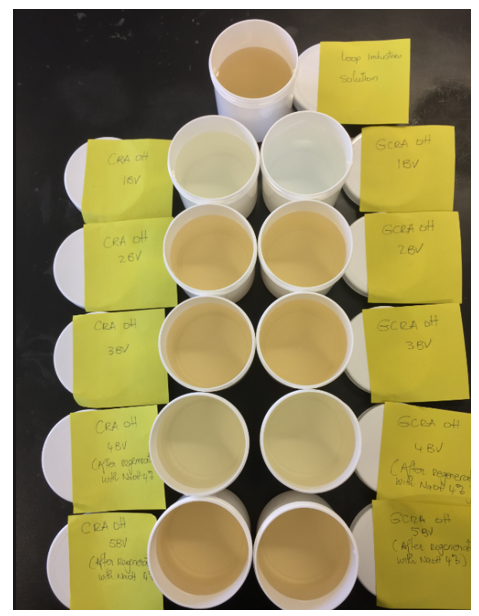

The analytical group would receive samples from the R&D lab, then work on the purification process and analyze the results. We received pictures and details of this analysis. For example, these photographs show tests to remove metals in the solution prior to a process called PTA precipitation:

We were also told that the problem was that the process being used in the R&D lab was not shared with the other lab – it was kept secret even within the company – supposedly because Solomita was worried that it would be leaked to competitors.

The second employee explained that processes in the R&D lab weren’t documented well enough for the analytical lab to know how the results were being achieved:

“In chemistry you get taught you have to follow a protocol. You have to write everything. You write what you do and you do what you write. You make a clear and explicit action plan beforehand. That’s something that you learn formally. That’s something you need to implement in your mentality.”

“Ultimately if you have your QC (quality control) that comes and tells you ‘Hey this is a really good batch, keep tweaking on these parameters’, you need to be able to know ‘OK what did I do exactly to get this particular sample. And I feel like there’s where there was a little bit of gap. If it wasn’t perfectly documented, then you don’t know how you got this really good sample…”

Former Employee: The Results Coming Out of the Secret Lab Were, At Times, Blatantly Impossible

The first former employee recounted to us how results coming out of the Essaddam lab were sometimes simply “impossible”. For example, in one case they claimed the process produced more solution than was initially put in. (Analogous to somehow turning 1 gallon of input into 2 gallons of output.) The employee concluded:

“I was not getting along with the Essaddam family. I am a very honest person, a chemist who respects the code of ethics. In my point of view, a lie and falsifying results is not acceptable. I was not shy to say it.

When a chem came from the lab into a meeting and said ‘I got it! I was successful’ I would say it’s impossible, you got more than what you sampled in the initial solution that you treated. They would say ‘no that’s not true.’”

Loop Claimed That the Base Chemicals It Created Were Of “Industrial Grade Purity”

A Former Employee Refuted This, Saying One Of The Base Chemicals Was “Not Even Isolated At The Time” And Was “Still Mixed With Dyes, Water and Solid Wastes”

Over three years ago, Loop was already claiming to have been able to create PET plastic building blocks that were of specifications needed for industrial use. This conveyed to investors that the process was consistently creating a viable end product.

In the company’s May 30, 2017, annual report, it describes its PET base chemicals (PTA and MEG monomers) as of “industrial grade purity”:

“Our depolymerized PET has been tested in third-party laboratory settings…and we have concluded that the PTA and MEG are of industrial grade purity, meaning they are suitable for use in commercial beverage bottles.” [Pg. 5]

But when we asked a former employee about these claims, they told us that not only wasn’t the output of industrial grade purity but the process was failing.

The MEG “was not even isolated at that time,” the former employee told us. It was “still mixed with dyes, water and solid wastes.”

The former employee also told us they “never saw any test report from an outside lab or manufacturer”. They believed Loop’s partner, Indorama, had used some base chemicals produced at a lab to create some bottles and that they may have been the “third party source” relating to these claims.

Loop Claimed It Was Able to Break PET Into Base Chemicals At A Recovery Rate “Of 100%”

Former Loop Employee: This Is Technically and Industrially “Impossible”

In the company’s June 15, 2016, annual report, it claimed to be breaking PET down into base chemicals at a recovery rate of “100%”. [Pg. 8]

“Our proprietary technology breaks down polyethylene yerephthalate (“PET”) into its base chemicals, purified terephthalic acid (“PTA”) and ethylene glycol (“EG”), at a recovery rate of 100%.”

We spoke to a former employee that worked at Loop around the time of this claim, who told us the claim of a 100% recovery was “technically impossible” and “industrially impossible”.

They also told us that “yields were not even repeatably over 90% at the lab scale” in October 2016, nearly 4 months after the company had already claimed a 100% recovery rate in public filings.

A polymer expert we interviewed, who has had no contact with the former employee, told us that a reclaim of 100% of PTA (purified terephthalic acid) and EG (ethylene glycol) base chemicals from PET is “impossible”. The expert also said that even “over 90%” would be “a stretch.”

Former Loop Employee: “I Don’t Think That [Loop’s Gen II] Process Will Be Successful. Actually, I Don’t Really Think They Have the Technology.”

Speaking about Loop’s new Generation II process we were told that it “wasn’t easier” than the earlier problem-ridden Generation I process:

“When I was there, they were producing PET and the contaminants had to be very low. We were successful every ten batches maybe, because there was always a contaminant that was way too high. We were trying to purify and repurify. Sometimes we’d purify a batch 4, 5, 6 times. On a material level it’s impossible to be successful and make money off of that. You’d have to send a batch back to reprocess because it’s full of contaminants—you can’t make money off of that.”

Despite Loop’s claims of a “revolutionary” process and “disrupting” the plastics industry, [4] the former employee told us they didn’t think the Gen II process would be successful, nor did they think that the company even has the technology it claims:

“There were so many issues with the process that we left it alone and we started a new process, but it wasn’t easier…I don’t think that it will be successful. Actually, I don’t really think they have the technology. That would be my conclusion”

Loop’s Own Patents Seem To Contradict The Company’s Claims About Yields, Purity and Lack Of Heat and Pressure In Its Process

In Loop’s October 2020 investor presentation, it emphasizes its “patent protected” technology. Instead of proving the value of the company’s intellectual property, the company’s patents and related applications instead seem to stand at odds with company disclosures and, in some cases, appear to disprove some of the company’s own statements.

The company has two patent families; one relating to its now defunct GEN I process and another related to its GEN II process. [Pg.5] The patents relating to the GEN II process [1, 2, 3] look to be Adel and Fares Essaddam brothers’ only patents. The main differences between the GEN II patents relate to the catalysts that the company is using to break down PET.

An expert chemist we consulted for this report called the GEN II patents “very similar” to the GEN I patent, which Loop CEO Daniel Solomita purchased in 2014 for $445,050 and has since written off Loop’s balance sheet. [Pg. F-15, F-16]

The company’s GEN II patents are replete with examples of adding both heat and pressure to Loop’s process. [5]

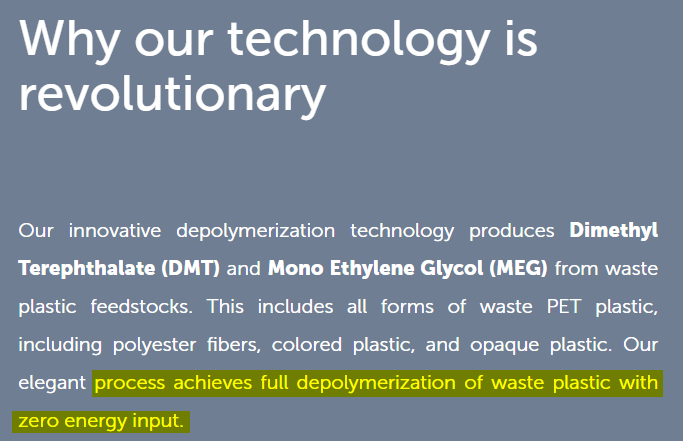

These revelations appear at odds with the company’s previous claims of breaking down PET “under normal atmospheric pressure and at room temperature” (likely referring to GEN I, from Q2 2017 10-Q) and claims made as recently as May 2019 (while describing the GEN II process), where on Loop’s website, in which the company says its process uses “zero energy input” and that this is “why the technology is revolutionary”.

Heat and pressure both require energy input, and thereby can substantially increase costs.

The GEN II patents also offer a glance into the company’s cherry-picked base chemical yields after breaking down PET. The results that the company admits to in its patents appear to be far worse than the “unparalleled” and “100% recovery” claims Loop has made in the past.

The data is cherrypicked for each base chemical, as well. For example, in this GEN II patent application [Pg. 22], data is presented in two different ways for each of the two base chemicals produced from the process, DMT and MEG.

The company chooses to show MEG yield after distillation, but not DMT yield after distillation. For MEG, it shows yield after only one distillation. Ergo, this makes it impossible to determine the purity of the final product based on the data provided; and certainly difficult to prove “unparalleled purity” after the multiple distillations that are likely necessary, our expert confirmed to us.

Additionally, a former employee informed us that the company’s MEG yield was being reported in the GEN II patent in a way that exaggerated the effectiveness of Loop’s process.[7] Even the inflated numbers do not qualify the process as high yielding, giving a false impression of the importance of the patent, the former employee said.

Part III: Loop’s Hollow Partnerships

Key to the investment thesis in Loop is its lineup of partnerships with major plastics-related corporations around the globe.

We connected with Loop’s partners and found the deals showed few signs of progress and mostly amounted to hollow press releases. Such empty partnerships are common in Environmental, Social and Governance (“ESG”) companies, providing major corporations an opportunity to “greenwash” or give the appearance that they are taking steps to help the environment, while doing very little to actually engage.

Loop’s Former Chief Growth Officer Used His Rolodex to Secure Partnerships With L’Oreal, Coca-Cola, PepsiCo And Other Major Corporations.

But These Partnerships Appear to Have Stalled. Loop’s Partners Would Not Disclose If They Had Recycled Any Plastic with Loop – Except One That Indicated It Had Received Nothing.

Just like other questionable companies of days past that have used various partnerships to project legitimacy, we think Loop is running a similar playbook.

In an October 2020 investor presentation, Loop touts its partnerships with companies like L’Oreal, Coca-Cola and PepsiCo.

We inquired with the above partners on the amount of plastic they processed in conjunction with Loop and were given vague answers, boilerplate responses or directed back to Loop.

For example, after emailing Coca-Cola European Partners for comment, we were diverted to an outside PR firm, Blurred London. After 13 days and several follow up emails, we received the following non-committal response:

“Loop is one of many technology providers working on developing efficient processes and alongside our bottling partners across the globe, the Company continues to evaluate several solutions to accelerate commercialization, in support of a circular economy for our packaging and our World Without Waste goals.”

Danone, owner of the world-famous Evian water brand, unveiled its recycled PET bottle in July 2020, saying it had been two years “in the making”. But none of the plastic or recycled resin came from Loop, even though the companies have a partnership agreement.

Responding via an outside PR company, Freuds, Evian said: “When Loop’s production site is operational, Evian will be one of the first brands purchasing LOOP PET to be produced.”

Loop currently has no operational production site in Europe or elsewhere – hence we view the statement as a roundabout admission that no Loop plastic has been used in the Evian bottle.

Loop’s Former Chief Growth Officer Told Us Multinational Partners Make Bets “On All Kinds Of Things” And Take “One or Two Years” To Do Rigorous Process Due Diligence After A Partnership Is Announced

We spoke with Loop’s former Chief Growth Officer, Nelson Switzer, (who has since resigned). Switzer indicated to us he had used his contacts from his former job as Chief Sustainability Officer of Nestle Waters to help entice some large names into partnerships [8]:

“As a former chief sustainability officer for one of the world’s largest CPGs (“consumer packaged goods”) I had and still have a very extensive network with other CPGs around the world and that was a big part of it.”

During our conversation with Switzer, he also seemed to confirm to us that larger corporations are fairly loose on signing vague sustainability or environmental partnerships:

“They’ll make these bets on all kinds of things whether its new technology or new enterprises or otherwise.”

Switzer also explained that turning such partnerships into production deals can take “one or two years” of due-diligence:

“…some of those things took one, or two years or more to qualify an additive or new type of plastic and there’s lot of reasons for it…in order to even consider that material into a production line we would have to make sure what the potential impact is on our production line. Is it going to contaminate anything? Do we have to worry about it?”

Switzer would not tell us whether Loop’s products were tested by multinationals (Pepsico, Coca-Cola, L’Oreal etc.) after announcing agreements, nor would he answer questions as to whether or not he stood alongside the production line and watched the process work.

Former Loop Employee: Partners “Couldn’t See The Entire Process. They Had To Believe The Results We Were Giving Them.”

A former employee of Loop told us that they didn’t think the potential partners could see Loop’s process from start to finish before entering into their partnerships:

“Danone spent an entire week with us. They wanted to see the process from the beginning to end…It was taking almost 2 weeks to finish a batch. So, they couldn’t see the entire process. They had to believe in the results we were giving them.”

Loop hasn’t disclosed a partnership with a major consumer brand name since Switzer resigned last May.

On September 28, 2020, Loop announced it had hired Sheila Morin as the company’s Chief Marketing Officer. Morin previously worked for both L’Oreal and Danone, two Loop partners, in the past.

Indorama Joint Venture: Announced By Loop In 2018 With An Expected Start Date Of Q1 2020 – Yet Indorama Tells Us The Project Is “Still Being Finalized”

One of the biggest partnerships the company touts is its joint venture with established global polyethylene manufacturer Indorama.

The 50-50 JV was announced on September 24, 2018. Both Loop and Indorama put $500,000 cash into the venture in April 2019. The company announced that the JV would have “an exclusive world-wide license to use Loop’s technology to produce 100% sustainably produced PET resin and polyester fiber with plans to begin commercial production in Q1 2020.”

Indorama was apparently so excited at the time that they suggested that Loop’s CEO should win a Nobel Prize, according to a 2019 article (translated from French) [9]:

“Mr Solomita recalls the reaction of Indorama’s main financier when the duo introduced him to their new technology: “He said to me: ‘if what you are saying is true, you deserve a Nobel Prize!'”

That excitement seems to have worn off. Now, both Loop and Indorama have indicated that the JV terms have not even been finalized, almost 2 years after the announcement. Loop’s most recent 10-Q, filed in October 2020 says:

“Discussions on the joint venture structure and financing are on-going.”

Indorama Exec #1: “The Project Is Still Being Finalized”

We reached out to Indorama to try to learn whether any work had been done to advance the project over the last two years.

Indorama’s SVP of Corporate Communications and Sustainability emailed us in mid-July saying they “cannot comment except to say [they] are actively pursuing partnership with Loop”, then said immediately afterward “the project is still being finalized”.

Indorama Exec #2: “Right Now, We Don’t Have Any Production”

We were also able to reach Sanjay Mehta, Chief Technology Officer in the Business Recycling Group for Indorama Ventures at the Spartanburg Plant in mid-August 2020:

“JV is in continuation mode and we continue to move forward and decide for the next quarter, how things are shaping relating to Covid and how the market is…So we are very cautiously watching it and then we are going to make a call next quarter…”

He declined to say whether the Spartanburg plant had been retrofitted with any of the equipment needed for the Loop process. When we asked him if there was any production using Loop’s technology now, Mehta commented:

“Right now we don’t have any production, that I can say. But I don’t want to give any more detail at this stage.”

Recently Announced Partnerships Seem to be Shifting Focus From Indorama

On September 3, 2020, Loop put out a press release announcing it had entered into an agreement to engage two outside firms called Chemtex and Invista Performance Technologies, the technology licensing arm of Invista, a major global producer of polymers and fiber.

The agreement is to help Loop develop its manufacturing processes, instead of collaborating with its longtime partners in Indorama, which has decades of experience in polymer manufacturing.

The company further appeared to be shifting focus from Indorama by recently entering into a “strategic partnership” with SUEZ, a traditional mechanical plastic recycler, to build Loop’s first “Infinite Loop” facility.

Given Indorama’s supposed close relationship to Loop, we can’t help but wonder why Indorama isn’t developing these facilities and – if it was offered the chance – why it passed on the opportunity. The commissioning of Loop’s new facility is projected for 2023, though like the Indorama joint venture, we doubt it comes to fruition.

Unlike Indorama, which is a chemical company with longstanding experience in end-to-end production of PET polymers, Suez is better known for sorting and managing waste streams and mechanically converting those into recyclable PET pellets.

A plastics industry source, with knowledge of Loop’s partnerships, told us:

“The competence of Suez makes sense because you have a partner dealing with the front end, the entire collecting, sorting, washing as a pre-treatment of what then what goes into depolymerization. But what is lacking, and the announcement is silent, is who will be the producer? Who will bring in the expertise for the entire production of depolymerization and polymerization again? Whether it is not Indorama or is Indorama – it’s silent on that question.”

Loop Partner Thyssenkrupp: Contract With Loop Is “Basically” On “Indefinite” Hold Due To Indorama Partnership Going “Silent”

On December 19, 2018, Loop entered into a “Global Alliance Agreement” with the industrial solutions division of ~$3 billion German multi-national engineering and steel company Thyssenkrupp. The press release boasted that the agreement with that division, called Uhde Inventa-Fischer GmbH, would be a “strategic alliance expected to shape the future of PET and Polyester manufacturing”.

The companies had planned to “license the respective technologies developed by Loop and thyssenkrupp Industrial Solutions to manufacturing partners in geographical regions around the world” by rolling out a “Waste To Resin” solution that would help companies achieve their goals of using 100% sustainable PET and polyester.

On October 12, 2020, we spoke to two senior executives at Uhde Inventa-Fischer GmbH.

We asked how they would characterize the state of Thyssenkrupp’s contract with Loop and were told by one senior executive that it was “on hold” and contingent on whether or not Loop moves forward with its Indorama partnership:

“It’s depending on whether there will be a first project or not (with Indorama). If there’s no first project there’s no path forward…It’s basically on hold. The contract is on hold and is silent on whether Indorama will further collaborate with Loop.”

A second executive at Uhde Inventa-Fischer GmbH confirmed this to us, stating:

“At the moment this (contract) is more or less for an indefinite time on hold. There was a project on-going with Loop but cooperation stopped maybe three months ago for the project with Indorama and since then according to my knowledge there is no further cooperation on-going and no further cooperation is planned.”

The second executive also told us that Thyssenkrupp was supposed to be involved, to some degree, in the Indorama partnership, but that it’s “not happening at the moment”:

“For the contract between Loop and Indorama I don’t know. That’s between them. But for our part we delivered the basic but there’s no further contract between us and Loop. At one time we talked about being involved in the detail but it’s not happening for the moment.”

Drinkfinity: A Short-Lived And Questionable Partnership With PepsiCo That Already Appears To Be On Its Last Legs

Another partnership that showed early promise appears to be on its way out.

In February 2017, the company signed a service agreement with Drinkfinity, a subsidiary of Pepsi, to provide customers with mailing envelopes so they can recycle their Drinkfinity pods. [S-A, Pg. 1]

A former employee told us of the program that one of the elements of the pods “is an aluminum foil, which could never be recovered by Loop’s process, being a metal”:

“In fact, in our tests, final PTA was highly contaminated by aluminum and was hard to remove being soluble in water like the PTA and insoluble in the solvents used to depolymerize the PET.”

As one article pointed out in 2018:

“The bags in which LOOP asks customers to send their empty Drinkfinity pods in are made from LDPE (low-density polyethylene) plastic, which LOOP’s technology cannot recycle – thereby appearing to place Loop in violation of their own agreement to recycle the packaging.”

A Seeking Alpha author ordered and scanned a shipping label for the Drinkfinity partnership. The label included in the article showed the pods were being mailed to St. Albans, Vermont.

The 7 Champlain Commons address on Loop’s mailing label corresponds to the red box shown here:

Photographs from a visit to the St. Albans site during September of 2019 showed a number of Loop’s Drinkfinity packages sitting in a couple of 55-gallon barrel drums:

To us, packaging a pod in non-recyclable LDPE, shipping it through the mail, only to drive it another 66 miles to Montreal doesn’t seem like a great use of resources – nor does it sound friendly to the environment.

Drinkfinity Partner: “I Don’t Know How Long Our Part In This Will Last…It’s Not Particularly Lucrative…We Don’t Make Sh*t Doing It.”

We contacted the businesses listed at the St. Albans address this year and learned that the Drinkfinity packages were being mailed to D&M Spools Prep, a recycling company. When reached for comment, D&M confirmed they were the middleman for receiving these pods in the U.S. and that the pods were then shipped to Montreal.

A D&M employee told us they were “currently under contract to send [the pods] back to Loop Industries in Canada”, adding “I know very little about what happens to the pods when they leave here.”

The employee told us that they had gone up to visit Loop in the hopes of entering into an agreement with them (outside of the Drinkfinity middle-man deal) but, after several months of waiting, learned that Loop wasn’t able to process D&M’s PET scraps:

“What their part is, I really have no idea. The way we got to know them (Loop) is we deal with PET – a lot of PET scraps. We had gone up to visit this company and they could supposedly turn it back into a liquid form – some sort of way. We sent them samples of our stuff and there was too many contaminants in it for them to be able to do it so we never really did anything with them.”

We asked if they were able to verify Loop’s process. They told us they were not and that it was “more of a meet-and-greet”:

“We weren’t allowed in – I don’t know if they had a laboratory set up. I don’t even know if we were on the actual site where they did it. It was a very small complex we went to. It was basically more just offices. It was more of just a meet-and-greet.”

Offering us their final thoughts on the partnership with Loop, they said:

“I don’t know how long our part in this is going to last. I don’t know if we’ll re-up. It’s not particularly lucrative for us. We don’t make sh*t doing it.”

It looks as though neither Pepsi, nor Loop, have kept up with the program. Drinkfinity’s (former) website at www.drinkfinity.com now just offers this message:

Part IV: Experts and Industry Participants Weigh In

In a Highly Unusual Move, The Company Hasn’t Published Any Of Its Recovery Rates Or Purity Standards Since 2017, Before It Began its Flagship Generation II Process.

In Loop’s October 2020 investor presentation, it refers to its technology as “proven” and claims that its end product is of “unparalleled purity”.

Many leading plastics companies (and startup companies in various scientific disciplines) publish peer reviewed studies or white papers that detail their advancements in the field. Contrary to that practice, we were unable to find a single peer reviewed study or white paper in any scholarly journal describing Loop’s process.

For comparison, French competitor Carbios published a study in Nature in April 2020 showing their small-batch study, after a 10-hour reaction time, recovered 90% of base plastic building blocks (monomers). Carbios is part of an official consortium between L’Oreal, Pepsico, Nestle Waters, and other major brands.

Our 30-Year Polymers Expert Consultant Called The Lack of Publications “Suspect”

We reached out to one expert in polymers/plastics with 30 years’ experience who has worked as a chemist for over three decades, holds several patents and has specific experience working with advanced methods of plastic recycling.

One of the things he asked us for was analytics on Loop’s process. But Loop doesn’t appear to have reported purity standards or recovery rates for its process since February 2017 – something that our chemist found baffling:

“It should be very straight forward. The analytical is the ‘proof’ of a process. Anything short of complete analytical support of a process should be suspect. The ‘secret sauce’ has no effect on the resultant analytical results of the products. Why won’t they share the process vs. analytical? I think I know why.”

30-Year Expert In Polymers: Loop’s Gen II Process Isn’t New, Isn’t Simple Or Easy, Isn’t Profitable And Involves Technology That Already Exists

The same 30-year expert told us that the company’s GEN II process involves technology that has existed for decades and is well known in the industry. He told us that when PET was first developed in 1941, then marketed by DuPont in 1951, scientists would have already “had a firm understanding of the properties” of the plastic. He said that rigorous testing leading up to the first bottle patent in 1973 meant the industry likely had a “thorough” understanding of hydrolysis and solvent resistance by then.

He noted that he did not see any type of special catalyst or trade secret in the patent that would preclude somebody else from doing the exact same thing that Loop is doing.

He said of Loop’s process:

“…the chemistry is there and has been there. Implying that it is ‘new’ and implying that it is ‘simple/ easy,’ and profitable as a standalone process, just isn’t true.”

Second Expert Consultant With 45 Years’ Experience: Loop’s Type Of Process Is “Very Well Known”

We also reached out to a second expert who has decades of experience with plastics and has worked in a number of positions in the industry, including as a project scientist for a company that merged with a $40 billion chemical company.

The second expert told us:

“I would concur with that opinion. He is right in saying it’s very well-known processing. Big companies like Coca Cola and so forth have been doing this for a number of years – depolymerizing.

But the purity of the materials they are working with originally is kind of high. They’re just recycling their own materials. But to get all the gunk out of there – with caps and paper – it’s kind of like a laborious process and has to come about pretty quickly before you even get to this point (depolymerization).”

During a discussion about how base chemicals could be reformed into usable PET plastic, we asked the second expert whether or not it would be a tough field to just break into for a new player, given the massive scale and already existing best practices in the industry by the major chemical companies:

“That’s correct. Boy you said it right there. I concur with that 100%. Yes, best practices – and many of those best practices are trade secrets as well.”

Loop Competitor: “We Could Not See Any Big Difference” From Loop and What Was Already Known in The Field Of Chemical Decomposition Of PET

We also reached out to a C-suite employee of a competitor for help on understanding how the advanced recycling field views Loop. We were offered a similar take to what our chemist told us, that Loop’s process is relatively well known:

“We started to pay attention (and) the first point to us was that the patent itself was not very detailed in the way things were done. We could not see any big difference away from what was already well known in the field of chemical decomposition of PET.”

30-Year Expert In Polymers: Loop’s Process For Breaking Down PET Plastic Is “Basic Stuff”, But Its Purification Process Is A Black Box

A polymer expert we spoke to told us that Loop’s processes for breaking down PET plastic are already well known, but that purifying the broken down plastic is the difficult step. He called this step in Loop’s process a “black box”.

What baffled him most was how the company could get from broken down PET plastic to usable, purified PET chemical building blocks again. He told us:

“I haven’t seen any references as to how Loop is refining the products to a usable form. Typically, processes such as distillation are used to refine, but that depends on the analytical results.”

He also told us that he believed this information has been omitted specifically because the process likely isn’t viable. He referred to Loop’s process as “basic stuff” and told us:

“The detailed information for either process is readily available to anyone. No ‘secret catalyst’ or ‘patented formulation’ additive is required. I do not know if any of the specific chemical pathways fall under someone’s current patent though. Wouldn’t think so. It’s basic stuff.”

We asked our chemist about the company’s statement that their “proprietary technology breaks down PET into its base chemicals, Purified Terephthalic Acid (PTA) and Mono Ethylene Glycol (MEG), at a recovery rate of over 90% and under normal atmospheric pressure and at room temperature”. [Pg. 6]

He told us that products created after breaking down the PET aren’t pure at that stage and need to be purified further to make the purified and usable end-product the company touts:

“…the ‘products’ are not pure. They really can’t be used unless pure. The statement is kind of misleading, in my opinion. While 90% conversion sounds good, it really isn’t. Polymerization is tricky. Contamination is really bad.”

Loop’s recent agreement with Chemtex and Invista, announced on September 3, 2020, indicates further to us that Loop has not shored up all parts of its process. Rather, it signals that the company is seeking help with purification and repolymerization. A former Loop employee, when asked about the agreement, confirmed it was likely because Loop needed help with this portion of its process.

45-Year Expert In Polymers/Plastics: “The Chemical Industry Has Been Working On [Re-Polymerization] For 50 Years”

Our second expert agreed that the purification portion of the process is where any secret sauce would be, and Loop hadn’t demonstrated any advancements. He concurred that this was the most challenging part of the process, telling us:

“The chemical industry has been working on this for 50 years. Or more. And they’ve put together very efficient processes in order to make the pure PET polymer.”

Loop Competitor: Purification Of Polymers Was The Key Question With Loop & The Sudden Switch To Gen II Was “Very Weird”

The competitor that we spoke to echoed the concerns of our chemist, telling us that purification of polymers was paramount and that the company’s sudden switch from Gen I to Gen II was “very weird”.

The competitor told us:

“Our question was how are they going to deal with this the moment that they purify the polymers and they must guarantee some food grade PET at the end, because that was the original purpose.”

Speaking about the switch from Generation I to Generation II, the same competitor said:

“If today our CEO came to us and told us you know what we’re going to change our reactions in terms of the impact, the reactor itself, but mostly the purification, what I would say is ‘Are you crazy? Are we restarting everything from scratch?’”

He continued:

“You are changing your impact on your business model. To us on the outside to us it sounded very weird.”

Loop Competitor Confirms: Separation Of Dyes Is “Hardest Part” Of The Process

The same competitor confirmed what our chemist and former employees had already told us; that purification and the separation of dyes was the crux of the process:

“Because the separation from the dyes and the organic element that are inside the PET waste and potentially dissolve in liquid is the most challenging part. It is where you have to start inserting some catalyst which is actually what most of our competitors tried to do, or in the case of Ionica they used some magnetic nanoparticles. But if you use a catalyst then you start to see chemical elements appearing in the final PET after you have depolymerized and this is where you get troubles with the purification.”

A former employee provided us with the details regarding Loop’s attempts to try and wash the PET with either water, P4 (dichloromethane) or both and the potential to reuse P4 without purifying it. The goal was to see if washing PET with used P4 could remove some dyes and make the final purification of MEG easier.

“No success,” we were told by the employee. “It was impossible to separate the different layers and recover the non-depolymerized PET.”

30-Year Expert In Polymers: “I Don’t See How You Could Make Any Money Or Save Any Money” Using Loop’s Process. “It’s A Scam In That Sense”.

We also inquired with our first expert as to why everybody in the plastics industry was not utilizing Loop’s process if it was as revolutionary as the company claimed. He responded:

“Everyone isn’t doing it because I don’t see how you could make any money or save any money in doing it.”

He concluded, upon his overview of the company’s Gen II process information that was available on the company’s website, by telling us:

“It appears to me that they took a very complex process, significantly simplified it, omitted a lot of serious stuff, and only mentioned the favorable highlights. I would say it’s a ‘scam’ in that sense.”

Loop Competitor: We Heard Rumors “Something May Not Be Working” At Loop. Their Credibility as A Competitor Is “Much Lower Than It Was 2-3 Years Ago”.

One of Loop’s competitors also told us that they were no longer worried about Loop as a competitor and that industry rumors were indicating to them that something may be amiss. They told us:

“With Loop, it’s sort of another world. We never met them in person, just secondhand speech. But to us, it’s not at the same level of competition that we thought it was….

If you sum all the things with the fluctuations of the stock value, of the contradictory information that we are provided in the quarterly reviews. Also copy and pasting of sentences in some press releases from other companies… All of these to us was a symptom of something going on behind the scenes that was not completely understandable to us.”

Plastic Recycling Partner Of $35 Billion Dow: “…I Never Heard Of These Guys Ever. Nobody Has Ever Talked To Me About Their Technology.”

To better understand whether Loop has had a meaningful impact on the recycling industry, and whether or not they are truly “on the radar” of large multi-national corporations, we reached out to large conglomerates to ask their opinion of Loop.

We were able to reach Rick Perez, CEO of Avangard Innovative, Houston, whose company announced a partnership with $35 billion market cap Dow in 2020, supplying post-consumer plastic film pellets to Dow.

He told us he had “never heard” of Loop and that “nobody has ever talked to [him] about [Loop’s] technology”:

“You need a team of people who know what they’re doing. I don’t know them (Loop). I never heard of them. Never been aware of any brand owner or converter (that has talked about them) and we move in the largest and biggest scale in the world and I never heard of these guys ever. Nobody has ever talked to me about their technology.”

When we described Loop’s process to him, he seemed uninspired:

“If you built the polymer then you can break it back down. I don’t consider that recycling. You bring it back to raw materials and put it back together again from the molecules. What is its carbon footprint…Are you really creating something environmentally friendly or just bringing a different process to the waste stream?”

Executive At Loop Partner Thyssenkrupp: Loop “Underestimated” Costs And “Underestimated” Process After Breaking Down PET To Its Base Chemicals

One senior executive we spoke to at Thyssenkrupp’s industrial division, when asked if he was familiar with Loop’s process, admitted to us they had “seen the weaknesses” in Loop’s process and alluded to cost being the “crucial point” on whether or not Loop’s process is viable:

“We got certain understanding (of Loop’s technology) by working on the development of a potential first integrated plant and have some insight there and a certain understanding of the potential of the technology and of certain ways to go and certain time and developments needed. We’ve also seen the weaknesses. I believe it’s more a matter of how economical such a technology at the end of day is. I would say you will always find a technical solution potentially. But what is the OPEX and CAPEX price for it? That’s the crucial point…”

A second executive told us that “the cooperation with Loop was very difficult” and that is why they stopped their Global Alliance agreement. He also said:

“The technology is available but they underestimated the cost I would say. So when they say it’s a profitable process, then going into the detailed figures it turns out it might be profitable but there’s a long way to go. And then there was a personal character thing which made things difficult.”

The second executive also confirmed to us that the purification portion of Loop’s process and the isolation of the base chemicals were stages in the process Loop had “underestimated”:

“The depolymerization definitely worked. The enzymes they’re using worked fine. But once you have a depolymerized solution then you need some kind of cleaning of that solution. You need to separate what the depolymerization process is giving you. It’s the separation they underestimated. It’s not their core business. They say they’re just focusing on depolymerization but the necessary cleaning steps of the solution were underestimated.”

Loop Has Never Generated Revenue And Warns Investors It May Never Achieve Or Maintain Profitability

Loop has never generated revenue and has an accumulated deficit of $62.3 million. [Pg. F-1] It has a history of widening net losses that leave us little faith that the company will ever generate income on its bottom line (or produce meaningful top line revenue, for that matter).

Loop has about $48 million in cash, given its balance last quarter and including a recent secondary offering. With a quarterly burn rate of about $5 million and planned capital expenditures for its production facility, we expect the company will need to raise more equity in order to advance its plans, should it ever choose to do so.

Conclusion And 15 Questions We Believe Management Should Answer

We think Loop’s claimed breakthroughs, which represent the entirety of its business prospects, simply don’t exist.

We also think investors in Loop deserve answers to the following questions:

- Was Daniel Solomita aware that Henry Lorin was a convict who had pled guilty to securities fraud charges when he was engaged to help raise early capital for Loop?

- If so, why did you hire a convict to help with your early capital raising efforts?

- Were you aware that Lance Bauerlein was under an active indictment for criminal securities fraud charges when you met with him to help facilitate Loop’s initial $80,000 investment?

- Did you expect that appointing two inexperienced individuals in their twenties with no post-graduate education in the sciences would yield a revolutionary breakthrough in the field of plastics recycling?

- According to several former employees, the R&D lab run by the Essaddams was producing results that couldn’t be replicated outside of their lab. How do you respond?

- Why does the company have two distinct labs? Is it best practice to limit access of the company’s scientists to a lab where major breakthroughs are said to be occurring?

- Loop’s competitors have published advancements and findings in scientific journals. Can Loop point us toward any relevant publications? If not, why has Loop not done this, despite all of the company’s claimed breakthroughs?

- When Loop claimed in 2017 that it was able to break down PET to its monomers at industrial grade purity, had MEG been consistently and successfully isolated at the time? Former employees state that it was mixed with dyes, water, and solid wastes. How do you respond?

- In 2016, Loop claimed to break down PET at a recovery rate of 100%. A polymer expert with over three decades of experience and former employees have described this recovery rate as “impossible”. How do you respond?

- Can you quantify exactly how much plastic Loop has recycled in conjunction with L’Oreal, Coca-Cola, and Danone since the announcement of these partnerships? Has there been any offtake from these companies, and if so, how much?

- Have L’Oreal, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, and Danone actually seen the entire Gen II process work from start to finish, using actual post-consumer waste PET?

- Why has it taken over 2 years to finalize terms of the joint venture with Indorama? Further, why did the company recently engage new partners instead of furthering its cooperation with Indorama?

- What is the status of the Drinkfinity partnership, given that the website doesn’t even appear to function?

- Why were Drinkfinity bags made with LDPE when Loop can’t recycle that plastic?

- We understand the company’s patents deal with depolymerization, but we also know these methods to be relatively well known already. Does the company have a patent on any specific purification methods that can be proven to purify PET monomers in way that exceeds the industry’s current best practices at an industrial scale?

We look forward to Loop’s answers to all of the above questions.

Disclosure: We are short shares of Loop Industries (NASDAQ:LOOP)

Legal Disclaimer

Use of Hindenburg Research’s research is at your own risk. In no event should Hindenburg Research or any affiliated party be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information in this report. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities covered herein. You should assume that as of the publication date of any short-biased report or letter, Hindenburg Research (possibly along with or through our members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or consultants) along with our clients and/or investors has a short position in all stocks (and/or options of the stock) covered herein, and therefore stands to realize significant gains in the event that the price of any stock covered herein declines. Following publication of any report or letter, we intend to continue transacting in the securities covered herein, and we may be long, short, or neutral at any time hereafter regardless of our initial recommendation, conclusions, or opinions. This is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. Hindenburg Research is not registered as an investment advisor in the United States or have similar registration in any other jurisdiction. To the best of our ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the stock covered herein or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Hindenburg Research makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Hindenburg Research does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein.

[1] “À l’époque, l’ingénieur et un partenaire, le chimiste Hatem Essaddam, ont construit un laboratoire de fortune, fabriqué avec des produits achetés à la quincaillerie locale, dans le but d’y faire des expériences. Ils espéraient développer une nouvelle technologie pour recycler le plastique de type PET (polyéthylène téréphtalate), utilisé dans la fabrication de bouteilles de plastique.”

[2] “On October 12th, 2014, the Company had a change in the management. The new management changed the name of the Company to Hitec Corp on November 4th, 2014. The new management decided that it is not generating sufficient revenue and has no hopes of future revenue from the recycling operations and impaired the asset of $600,000.”

[3] “The Company has determined that it have [sic] no intent of commercializing the GEN I technology.” [Pg. F-16]

[4] Loop’s website on October 12, 2020: “Disrupt traditional plastic and fiber manufacturing” and “Why our technology is revolutionary”

[5] See WO2020/002999 here. Addition of heat to portions of Loop’s process can be found in numerous examples, such as lines [0015], [0033], [0034], [0036], [00114], et al. Use of pressure can be found in line [00148] in the previously linked example and line [0136] in the company’s US patent here.

[6] The company’s website, as of October 11, 2020 now says “Our depolymerization process achieves this using low heat and no pressure” and calls the company’s technology “low-energy”.

[7] The former employee told us: “Usually you report a yield according to the theoretical amount the depolymerization should generate, not based on what you found in your reactor after the reaction. So it means that the true yields are even lower than the ones listed…”

[8] Additionally, his LinkedIn states he: “(I) Led sales & marketing to successfully secure multi-year agreements with PepsiCo, Coca-Cola, L’Oreal, Nestle Waters, L’Occitane and other global consumer packaged goods companies – selling Loop’s total planned production capacity. (I) Developed supply chain pipeline of waste PET to satisfy the feedstock requirements for Loop’s total planned production capacity.”

[9] “M. Solomita se souvient de la réaction du principal financier d’Indorama, lorsque le duo lui a présenté sa nouvelle technologie: «Il m’a dit: “si ce que vous dites est vrai, vous méritez un prix Nobel!”»”

83 thoughts on “Loop Industries: Former Employees and Plastics Experts Blow The Whistle On This “Recycled” Smoke And Mirrors Show”

Comments are closed.

Next do Tesla

YEAH. Like if Tesla were building fake cars. Good call.

Have you tried getting an informant to apply for a job to the company? Much could be learned in the “interview” process–including site visits, and review of the NDA forms.

I’ve been suspicious of these guys since the first time they sent me a press release. They were silent for a long time — I wondered why no PR about their progress — only PR about their JVs with the big brand owners. Looks like Pepsi, Coke, etc. didn’t vet this group very good — the desire for the Holy Grail of recycling is so strong that these brand owners, it seems, will grasp onto anything without any vetting whatsoever. Keep me posted on further information. I am Senior Contributing Editor with PlasticsToday.com and have been in the plastics industry for 35 years.

thanks for unraveling this anomaly

Unlike GRWG, the one thing that seems missing here is large insider selling of shares.

Maybe they really believe in their process, or are just drinking the Kool-Aid that they will eventually get there a la Elizabeth Holmes at Theranos.

I fear there are more like this out there. As a journalist for the plastics industry, I’ve become very suspicious over the past 2 years. I’ve seen a lot of big promises (in the millions of tons) for recycling plastic waste, a lot of fanfare over proposed plants, a lot of money gotten from investors and then —- crickets! I’ve had some off-the-record conversations with some industry insiders who also have been questioning. It appears to be an industry ripe for taking the money and running! I’m watching closely!

Nice!

Those rascals! New short sell to make, thanks Hindenburg!!!

As a plastics industry journalist I’ve got my eye on a few others out there. This is an industry ripe for fraud. Smoke and mirrors describes much of it perfectly. Plastics is a science — NOT magic!

Great work!

I have myself hired the Essaddams when they arrived in Canada in late 2011, his sons were still in highschool, and the father sold me thick black smoke and got me and other shareholders into investing personal money for over 225 000$ plus commitments to banks and others before leaving 2,5 years later, to work for Daniel Solomita who promised to pay him hundreds of dollars ”to catch flies” (in his own words)!!! Then, Essaddam sued us for false reasons just to weaken us, which largely lead us to go bankrupt.

Hatem Essaddam is the most dishonest and mal intention person I know, only eager for his own personal wealth, and he is now working with someone I have heard was no angel either in his previous business Dragon Polymers (at least one of his associate seems to have been arrested for major financial fraud in the province of Quebec, Canada). So in clear, what’s written in the Hindenburg report, I have lived most of it, making me, my ex-associates and my other ex-employee (Ph D) definitely supportive of all allegations provided in the Hindenburg report.

Here’s a press release that followed the Hindenburg report publication (use Google translate for better understanding): https://www.lapresse.ca/affaires/entreprises/2020-10-29/l-inventeur-de-la-technologie-de-loop-poursuivi-par-ses-anciens-employeurs.php

LOOP: Depolymerizing Fiction to Distill Facts

We review key assertions by Hindenburg which are presented to discredit LOOP’s independent technology review. Similar to the first short report, we question the accuracy and / or understanding of a good portion of the report’s assertions. At best, they are from sources unfamiliar with the technology. At worst, they intentionally leave out material information to bolster their argument.

The Hindenburg report takes shots at LOOP’s independent technology review by questioning Kemitek’s process and role. We question many of the short report’s assertions as it either leaves critical information out of their statements or just represents a poor understanding of the process. The report relies on unnamed former employee(s) and a “chemist,” neither of whom do we know their backgrounds or credentials. Further, these sources provide comments, which we frankly find lacking in merit or understanding of the LOOP process. In the end, the Kemitek report should provide a level of confidence that LOOP’s technology is valid and investors should refocus on LOOP’s execution on the buildout of its Infinite LOOP facility. For an overview of the Kemitek report please see our note HERE.

Former employee represented as key insider. Several comments by the employee source(s) lead us to question their depth of knowledge and expertise. Further, at a minimum it is likely the source has not been at the company for several years. We glean this from most of the commentary in the original short report, which appeared to be centered on Gen I technology. Key assertions attributed to the employee source which lead us to question their credentials are as follows:

■ Questions around PET source material. The employee source suggests that PET input material should include “rock and sand for more accurate tests.” Anyone with rudimentary understanding of filtration processes would know rock & sand can be easily be separated by settling tanks or other cheap and inexpensive processes. This comment does not “float.” Further, the short report’s “chemist” questions the composition of the PET source material. Our work with multiple recycling companies and channel checks with plastic recycling aggregators indicate PET material is contracted at specific concentration levels. For example, some suppliers will provide material which is 85% PET while others provide material which is 95% PET. For reference, mechanical recyclers who rely on post-consumer waste (curb side pickup) contract for material in the 50-60% range, however, this is overwhelmingly PET bottles.

■ Purity concerns don’t work either. As per a direct quote: “The employees told us that 98.2 – 98.9% MEG purity in the review was far from the 99.9% MEG purity that was expected.” In our work with LOOP, it has never expressed the need for these levels of purity. Secondly, MEG purity levels reported in the Kemitek report are in line with the LOOP’s MEG specification, which was approved by the European Chemical Agency on November 17, 2020. The approval states LOOP’s MEG is within EU standards and the monomer can be imported or manufactured in the region. LOOP’s DMT monomer received the same approval on December 7, 2020. Finally, the other trace monomers found in the MEG are actually used in PET production and as noted by Kemitek in its report “these additional monomers (DMI, DMT, BHET, MHET) found at presented levels are appropriate for PET production.” This key comment was not presented in the short report.

• Data is averaged or selected for better results. The report and source state data is presented inconsistently and questions why two “batches” of MEG were combined for analysis purposes- inferring that this was done to average for better results. This inference highlights a lack of understanding with the process and pilot plant set up. The depolymerization process does not create DMT and MEG in 1:1 ratio. The process train creates MEG material which is approximately 1/3 of the output, with DMT accounting for the other output. In the MEG process approximately 800kg of used PET material is inputted with an output of 264kg (33%). The next step in the process is distillation towers which require 500kg of material – hence two runs are required. Kemitek would likely have flagged the issue if runs were combined for better results.

• Not ready for prime time? The former employee states LOOP’s process is not ready for industrialization and scale up to production level. This assertion is based on Kemitek’s comment that certain processes during their test & review needed intervention including clogged lines. However, Kemitek noted that these type issues are common in pilot sized equipment. Further, Kemitek’ business is to help companies to scale. Kemitek likely has a greater insight into this issue than a former employee who we believe has not seen the Gen II process.

Chemist with 30 years’ experience. As for the chemist with 30 years’ experience. Who are they? What’s their expertise with plastic monomers / polymers? Are they practicing? What’s their formal education? Do they have experience with technology transfer and scaling up processes? Have they spoken with management to get better understanding of their questions or are they casual observers opining on process technology?

Conclusion – rubber hits the road. At the end of the day, the key question is whether LOOP’s technology can scale economically. Since we began our work, we have maintained this has been a risk and will be a risk until a commercial plant answers the question. We also believe the LOOP business model incrementally de- risks itself as it moves closer to commercialization. This includes validation of the process, material supply contracts with CPG groups and the development and signing of agreements with producers. These steps have been completed via agreements from multiple CPG companies, Suez, and Indorama. In our view, the next substantial step for LOOP, and the focus for investors, should be the ordering of long lead time equipment and shovels hitting the ground for its Infinite LOOP facility.