Summary: Bloom Energy (NYSE:BE)

- We believe that Bloom Energy, once touted as the prospective “holy grail” of clean energy, is instead likely to wind up in the history books alongside failed companies like Theranos or Solyndra.

- Contrary to myths about Bloom, our research indicates that Bloom’s technology is not sustainable, clean, green, or remotely profitable.

- We uncovered an estimated $2.2 billion in undisclosed servicing liabilities that the market has missed, even in its most recent re-valuation of Bloom shares. These issues have already begun to surface and we expect they will accelerate.

- Bloom’s tricky accounting allows it to mask servicing costs and shift write-downs to other periods, thereby avoiding recognizing major recent additional losses.

- We believe that large debt maturities in 2020 and 2021, amounting to nearly $520 million, make Bloom Energy an obvious bankruptcy candidate.

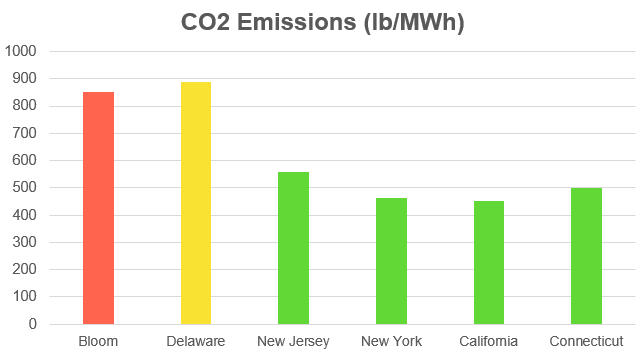

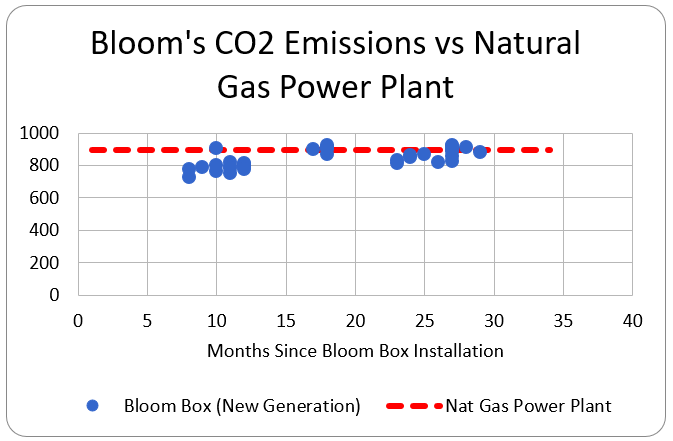

- The company’s “clean” narrative is absurd: our research shows that Bloom Energy servers emit significantly more CO2 than the electric grid in key states where it operates. Its emissions are comparable to those of modern natural gas power plants.

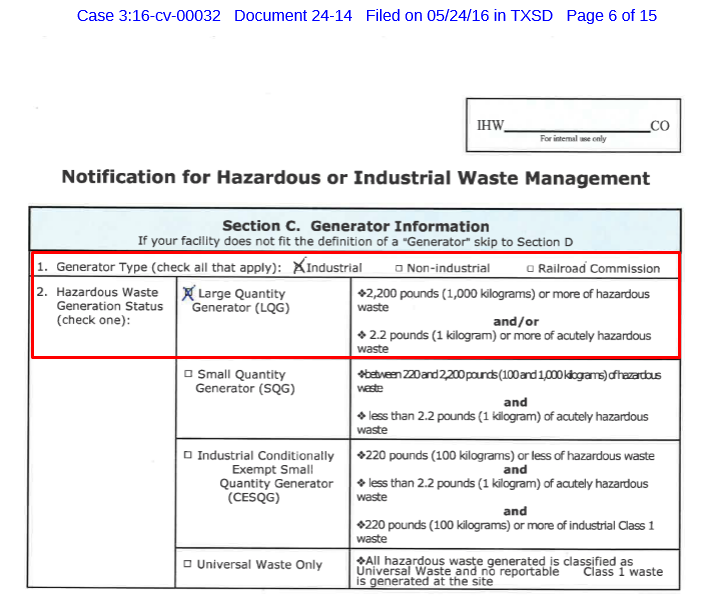

- Court documents reveal that Bloom self-identified as a “large quantity generator of hazardous waste,” to the EPA. Bloom was even sued in 2016 over alleged deceptive trade practices relating to the dumping of its hazardous waste in California landfills.

- Bloom has collected over $1.1 billion in federal, state, and local subsidies. Many of these subsidies are being withdrawn or stepped down as jurisdictions wise up to the reality of Bloom’s products.

- A former Bloom employee and a fuel cell expert told us, respectively, that Bloom “probably wouldn’t exist today” without subsidies and that Bloom “hurts the fuel cell industry overall”.

- Bloom executives have a history of making allegedly false statements, including ones it was forced to retract in SEC filings. In another case, Bloom paid $16.7 million to settle allegations that it lied to its brokers.

Initial Disclosure: After extensive research, we have taken a short position in shares of Bloom. This report represents our opinion, and we encourage every reader to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report.

Part I: Bloom’s Fantasy Origins

The market appears to be slowly waking up to the same unfortunate conclusion about Bloom Energy that we have arrived at after several months of rigorous deep dive research. Instead of being a great clean energy success, we expect Bloom’s “too good to be true” story will find its place in history along the likes of defunct companies such as Solyndra and Theranos.

Bloom is a technology company that develops and manufactures stationary fuel cell systems. Bloom’s systems, called “Bloom Boxes”, are essentially generators that businesses can use to create on-site energy using solid oxide fuel cells, a technology that has been around for almost a hundred years.

The boxes take an input, usually natural gas, and convert it into usable electricity.

Fuel cells, in general, have been understood by the scientific community since the early 1800’s and have been a largely unprofitable industry to date. Much of Bloom’s popularity (and funding) was based on the idea that it could “break through” as the first profitable and sustainable fuel cell company, they had a solid business idea that would be able to provide Business Utilities at a fraction of the price the business was originally paying for their utilities.

The company was founded in 2001 by KR Sridhar, a well-credentialed scientist who developed fuel cell technology at NASA before launching Bloom, quickly gaining the support of brand-name venture capitalists, such as Kleiner Perkins.

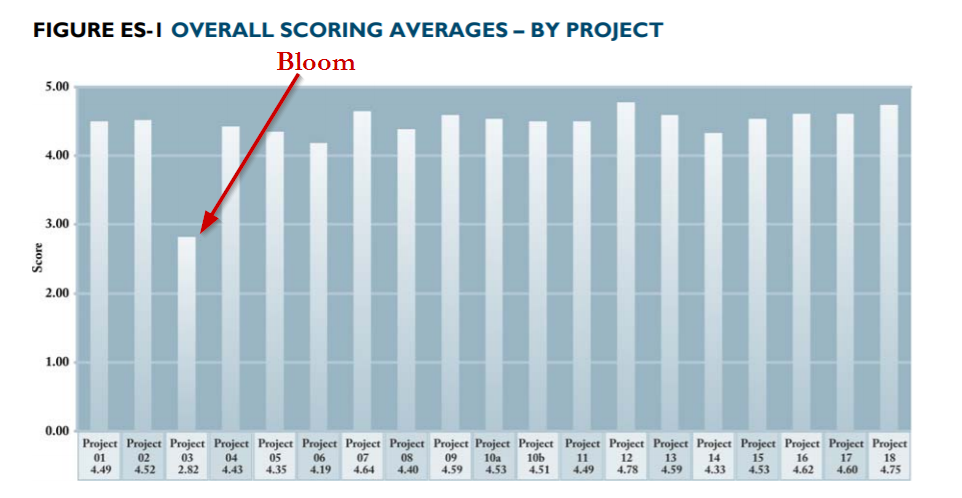

By early 2008, a Department of Energy report [1] ranking solid oxide fuel cell projects by effectiveness placed Bloom’s dead last by a wide margin:

Nonetheless, later that year, the company booked a high-profile Kleiner Perkins alumni as its first customer: Google. The search behemoth installed a 400 kW Bloom system at its main campus that year (and doesn’t appear to have expanded its relationship with Bloom since).

Bloom’s big unveiling to the public took place in 2010 on national television. Upon its release, Bloom was heralded as a scientific breakthrough by a litany of the nation’s top non-scientists. Senator Dianne Feinstein declared of Bloom:

“This technology is fundamentally going to change the world.”

Other notable non-scientists, such as Arnold Schwarzenegger, former Secretary of State George Schultz (of Theranos infamy), and former Secretary of State Colin Powell, who is a current Bloom board member, voiced their full-throated support for the company.

That same year, 60 Minutes ran a puff piece on Bloom, introducing the program by saying “in a world of energy, the holy grail is a power source that’s inexpensive and clean, with no emissions.”

With the wind at its back, Bloom rolled out its product to a “Who’s Who” of Fortune 100 companies, including AT&T and Home Depot, regularly guaranteeing them long-term attractive energy prices with agreements that lasted up to 25 years. These agreements placed the risk of the company’s fuel cell performance squarely on Bloom and its shareholders. Many customers, seeing the attractive guarantees, took the deals and held up their Bloom Boxes as evidence of a commitment to green, clean, and sustainable energy.

It was a storied beginning to a company that was slated to revolutionize global energy and change the world as we know it.

But nearly a decade later, the company has been unable to fulfill its ambitions of being profitable and the realities of our research have led us to one conclusion: We expect Bloom Energy will become yet another tombstone in the Silicon Valley cemetery of dead unicorns. Once again making energy consumers look for the best electricity rates in Texas and other states in which Bloom wanted to supply their sustainable energy.

Bloom’s Operational Reality: An Emissions-Spewing, Hazardous Waste-Creating, Uneconomical Product That is Failing in The Real World

Let’s start off our series of inconvenient truths by making one thing clear: Bloom has never been a “green” energy company.

While being capable of running on biogas (a form of genuine green energy), 91% of the company’s fuel cell products run on natural gas (a non-renewable fossil fuel). [Pg. 5]

Bloom is also not a “clean” energy company. Instead of reducing emissions, data we collected from hundreds of Bloom projects shows that they generate more CO2 than the electric grid in key states they operate in and produce CO2 levels comparable to modern natural gas power plants.

Bloom’s generators also result in the creation of carcinogenic hazardous waste, which the company has allegedly improperly dumped into public landfills. Lawsuit exhibits reveal that Bloom labeled itself with the EPA as a “large quantity generator” of hazardous waste. The exhibits include pictures of Bloom employees wearing respirators as they handle 55-gallon drums of what appears to be hazardous waste from emptied/cleaned collection canisters.

To make matters worse, the company has procured over $1.1 billion in federal, state, and local subsidies, often under the auspices of being green, clean, or renewable. As we will show, Bloom is none of these and lately, multiple states have wised up and begun to withdraw or step-down subsidies as a result – a move that we expect will further cripple Bloom’s business model.

Bloom’s Economic Reality: Never Been Profitable, No Expected 2020 Revenue Growth, An Estimated $2+ Billion Undisclosed Servicing Liability and Losing Subsidies

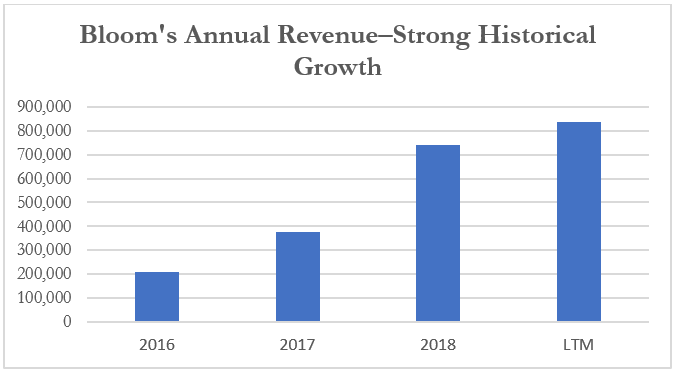

Astonishingly, Bloom has never been profitable despite its significant historical revenue growth and despite receiving over $1.1 billion in subsidies.

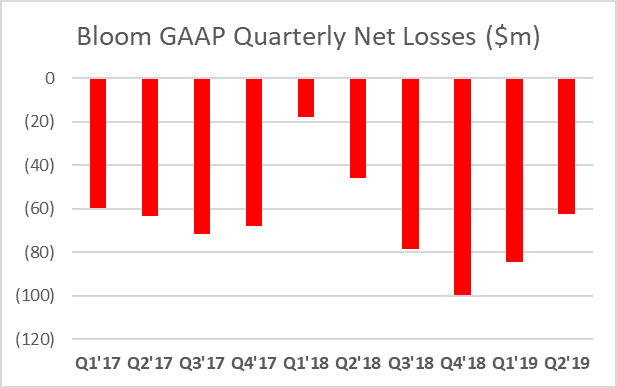

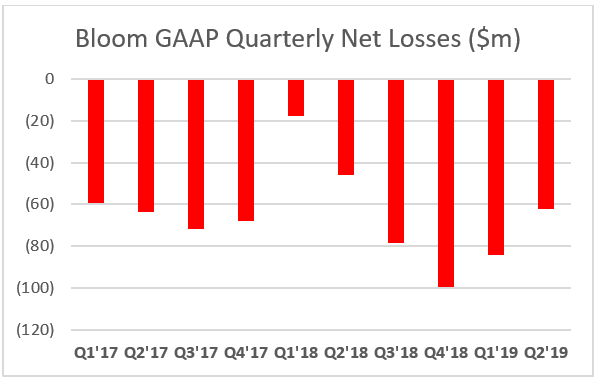

This chart shows Bloom’s quarterly net results, inclusive of its historic tailwinds:

With the company’s “bag of tricks” now empty and newly offered tepid guidance, we expect these red bars to drop materially lower going forward.

Recent Conference Call: No Revenue Growth For 2020. The company recently acknowledged that it expects no revenue growth next year. Bloom hoped to achieve manufacturing economies of scale to lower costs and enhance its profitability, but in the absence of growth, high overhead will further imperil profitability.

Subsidies Disappearing. Subsidies are disappearing entirely or being stepped down over time. We estimate that the stepping down of the Federal Investment Tax Credit (ITC), for example, will represent $247 million in foregone subsidies over the next 3 years.

Bloom’s Unsustainable Debt Burden: Large 2020 and 2021 Maturities Make this an Obvious Bankruptcy Candidate

Bloom’s debt situation has reached unsustainable levels. Per its most recently quarterly report, Bloom has just $308 million in cash on hand, down from $325.1 million in December 2018. By the end of 2020, $379.2 million in debt is coming due, with significant 2021 maturities thereafter:

Per the same quarterly report, the company now has $701.3 million in total debt, with $431.7 million of that total listed as recourse debt.

The largest chunk of the company’s debt is $296.2 million from its 6% convertible promissory notes due December 2020. These notes present a problem for the company, as the conversion price is now far out of the money, at $11.25 per share. This likely means that, upon maturity, Bloom will have to put up the cash, unless it can enter into a refinancing (which would likely be on toxic terms).

Beyond the debt, we have also uncovered another massive liability, seemingly unknown to the investing public, that we believe will seal Bloom’s demise.

Bloom Energy Has an Estimated $2.2 Billion In Undisclosed Servicing Liabilities That We Expect Will Sink the Business

The Crux of the Problem: Bloom Places Itself on the Hook for the Long-Term Performance of Its Systems (And Field Data Shows They Don’t Last Long)

Backing up for a moment, one might ask—how does a new, relatively unproven company like Bloom manage to sell so many fuel cell systems to so many Fortune 100 companies, when fuel cell economics have repeatedly failed in the real world?

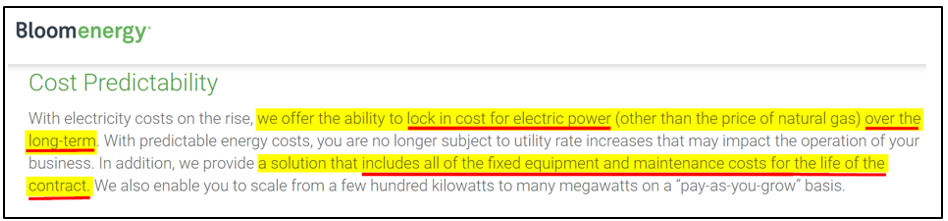

The answer is that Bloom’s contracts guarantee baseline performance levels—essentially locking in the price of electricity for its customers. Per Bloom’s marketing literature:

“We offer the ability to lock in cost for electric power (other than the price of natural gas) over the long-term…we provide a solution that includes all of the fixed-equipment and maintenance costs for the life of the contract.”

These contracts place nearly 100% of the risk on Bloom and are very long-term—typically lasting from 10 to 21 years [Pg. 101] and lasting as long as 25 years. [Pg. 14]

This is an incredibly attractive deal for customers, who can (and do) tout their forward-thinking ways while also locking in cheap electricity.

Conversely, what this means for Bloom is that when the electrical output of its systems decline—they are on the hook to replace them. Bloom has noted this as a key risk in its filings:

“If our estimates of useful life for our Energy Servers are inaccurate or we do not meet service and performance warranties and guarantees, or if we fail to accrue adequate warranty and guaranty reserves, our business and financial results could be harmed.” (10-Q Pg. 70)

Bloom is responsible for two types of replacements: its fuel cell servers (the system itself) and the individual fuel cells that go inside the servers.

As experts have confirmed to us, the high operating temperatures of solid oxide fuel cells (800C or 1400F, and higher) make them extremely susceptible to wear and tear.

A fuel cell technician with 19 years of experience in the field made this clear to us and brought up what would be a recurring theme with multiple experts we spoke to, durability:

“Bloom Energy is also a high temperature type application. They are using solid oxide fuel cells, which is a very temperamental fuel cell in the first place. High temperatures create a lot of issues whenever you’re dealing with the expansion of different components in it. I mean, you’re going up to 7-8-900 C. Whenever you’re hitting those kinds of temperatures and then you’re cooling back down, everything is expanding and contracting at different rates and those type of fuel cells suffer significantly from breakage through those varying thermal cycles.”

Our research has found that Bloom’s fuel cells and systems degrade significantly faster than expectations, yet the company barely records any liability for these issues.

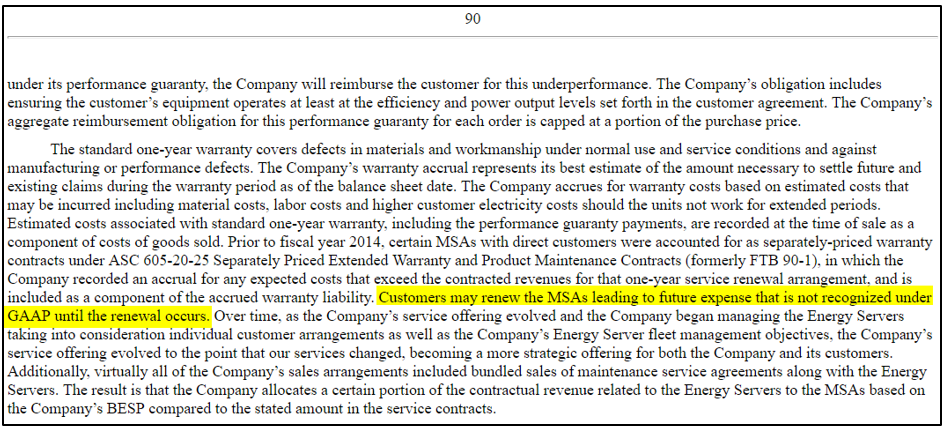

No One Seems to Have Noticed the Accounting Trick That Allows Bloom to Mask Its Liabilities: The Company Only Discloses 1 Year of Servicing Liabilities Despite Servicing Contracts that Last Up to 25 Years

So, how does Bloom justify largely ignoring its multi-year servicing liabilities?

We found a simple little line, buried on page 91 of Bloom’s 10-K, that explains it. (Note that this line was NOT in the company’s IPO prospectus):

“Customers may renew the MSAs (master service agreements) leading to future expense that is not recognized under GAAP until the renewal occurs.” [Pg. 91]

At first glance, this line looks rather benign. But what it means is that the company only books the next year of servicing liabilities, rather than accounting for the liabilities across the full 10-25 years of the contract.

Why? Because technically the customers have the option to renew their service contract every year that they could – technically – choose not to exercise. Per the same filing:

“The warranty and guaranty may be renewed annually at the customer’s option – as an operations and maintenance services agreement – at predetermined prices for a period of up to 25 years.” [Pg. 39]

The obvious question is: why wouldn’t they renew? What customer wouldn’t push a ‘free money’ button that essentially guarantees them cheap, long-term electricity by renewing their service contract?

Even Bloom acknowledges that customers don’t cancel these agreements:

“virtually no customers have elected to cancel their maintenance agreements” [Prospectus Pg. 123]

We found zero examples of customers not renewing these service agreements. Nonetheless, Bloom records its servicing liabilities as if every customer will cancel every year. It’s no surprise why this seems to have gone largely unnoticed given where it was buried in the financials:

We have contacted the company and asked about its servicing liability accounting, as well as the actual life of its new generation fuel cells and servers. We have not heard back as of this writing. Should we hear back, we will update this piece accordingly.

Bloom: “We Expect to Average Over Five Years Between (Fuel Cell) Replacements”

Reality: Field Data Suggests Replacements Are Needed Before 3 Years, on Average

We have sourced extensive public data in order to track how Bloom’s systems are actually performing.

As stated earlier, the major costs associated with Bloom’s long-term service liabilities relate to degradation or damage to its (1) fuel cells and (2) fuel cell servers.

We’ll start by discussing its fuel cells.

Bloom has claimed to have made big improvements to the life of its fuel cells, stating that fuel cells installed in 2017 and onward will have a lifespan of over five years:

“Time to stack replacement’ primarily driven by our fuel cell stack lives—in the early years, replacement was typically 12 to 18 months. Over the years we have made steady improvements in our fuel cell lives, and from 2017 onwards we expect to average over five years between replacements.” [IPO Prospectus Pg. 61]

We have tracked data on Bloom projects installed since 2017 through state utility records in New York and California. There were 35 projects in all. After aggregating this data, we found that even Bloom’s newest fuel cells will degrade below replacement thresholds in under 3 years, significantly below the company’s “expectations”. We present this data later in the report.

Our findings were corroborated by multiple experts in the field who were highly skeptical of Bloom’s claim that solid oxide fuel cells could last 5 years or longer in the field.

We asked one professional fuel cell technician, with 19 years of experience, whether he believed the company’s claims to be able to run solid oxide fuel cells for 5 years. He responded with a curt “no”. When asked if the same fuel cells could operate for three years, he replied:

“Do I believe claims of 3 years before service is needed? No. I would be highly skeptical.”

Another expert we contacted, with 14 years of experience working in Fuel Cells and Fuel Cell Performance Analysis, who also has a B.S., M.S., and a PhD in Chemical Engineering, also warned about temperature and durability preventing Bloom’s cells from running for 5 years:

“They are using the high temperature materials, I think. So, there is advantages and disadvantages. The disadvantage is that degradation is probably high. I doubt they have 5 years life. They may have 1 or 2 max. They cannot achieve 5 years. Or maybe if they have to replace part of the stack, they can achieve 5 years. In general, it’s really hard for SOFCs to run 5 years.”

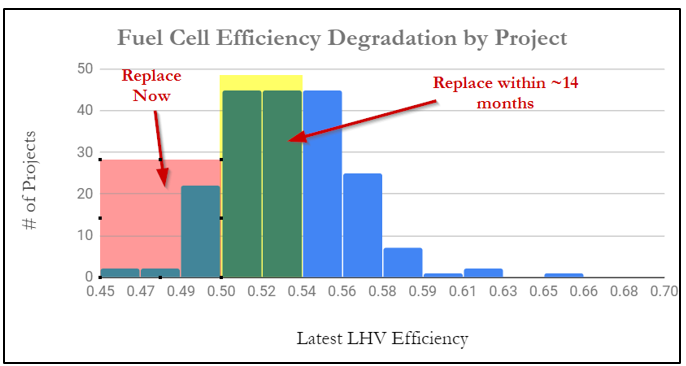

Bloom’s Unrecorded Servicing Liabilities: Project Data Shows That Fuel Cells in The Field Will Need Replacement Far Quicker Than the Company Lets On

Keep in mind that Bloom guarantees both the output (total electricity produced) and the efficiency (how much fuel is used to generate the electricity) of its servers:

“…we typically provide an Output Guaranty of 95% measured annually and an Efficiency Guaranty of 52% measured cumulatively” [Prospectus pg. 75]

Bloom also provides tighter 80% quarterly output guarantees or 45% monthly efficiency guarantees on some of its projects. [Prospectus pg. 88 and 89]

Efficiency and output decline together: As the systems become less efficient, they produce less electricity, making efficiency degradation key to when fuel cells need to be replaced.

As we have seen from older Bloom project data in California and New York, fuel cell replacements were typically done in the 48%-50% efficiency range.

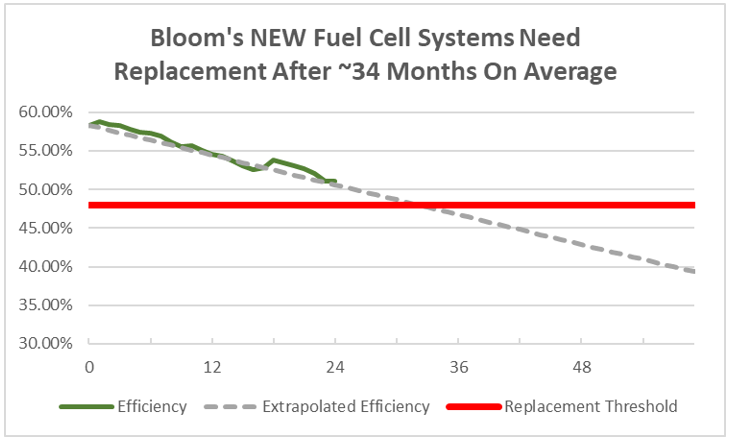

This chart, based on data from California and New York, shows how rapidly Bloom’s newer post-2016 installed servers are declining by month, on average. It also shows how the trend continues:

After only 25 months, Bloom’s newer fuel cell installations had deteriorated from a median starting efficiency of 58.3% down to 51.0%, a decline that puts them on pace to breach the 48% threshold with 34 months (less than three years).[1]

The chart also shows that 45% efficiency (which serves as a ‘bare minimum’ on some projects) will be breached after only 42 months, or 3.5 years.[2]

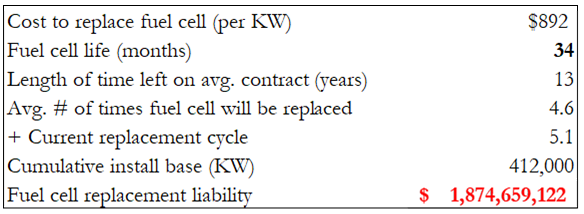

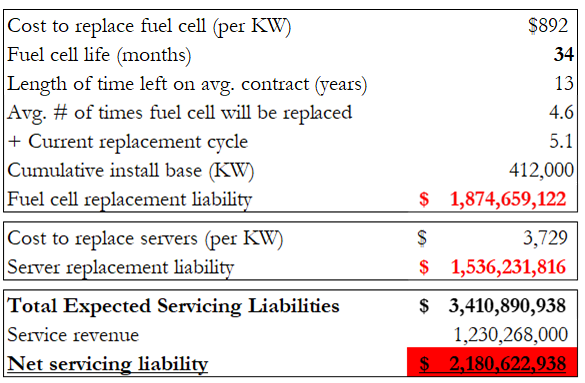

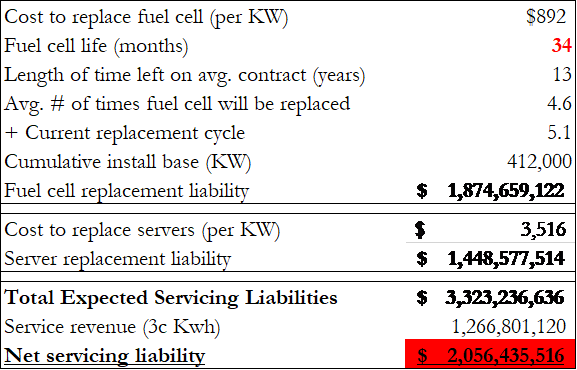

This multi-year difference between expectation and reality will translate to an estimated $1.87 billion in fuel cell replacement costs:

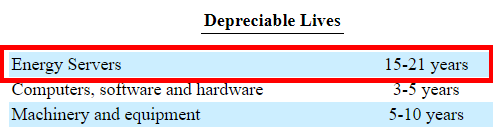

Bloom’s Unrecorded Servicing Liabilities: Bloom Estimates Its Fuel Cell Servers Last 15-21 Years

News Flash: They Don’t. The Company Has Historically Replaced Servers After Just 4-7 Years

Moving on to the liabilities associated with replacing Bloom’s servers (as opposed to just the fuel cells), our first check was to see how long the company estimates they will last. Keep in mind that these systems run continuously at temperatures around 800C (or 1400F) in real-world conditions.

Bloom shows, in its depreciation schedule, that it expects its servers to last for 15-21 years [Pg. 95]:

We think this depreciation schedule is horribly askew from reality.

For instance, Bloom sold servers in 2010-2012 that lasted only 4-6 years. They had been replaced entirely by 2016. [Pg. F-39]

Bloom also installed servers in Delaware in 2012 that are now being replaced after just 7 years, as announced this past quarter. [Pg. 11]

The company itself acknowledged that it had failed to achieve its own estimates previously:

“Early generations of our Energy Server did not have the useful life and did not perform at an output and efficiency level that we expected.” [Pg. 70]

We are now being asked to trust the new estimates, which look to represent approximately a 3x improvement on prior server lifespans. Yet the company thoroughly disclaims its own estimates, declaring them to be a key risk factor:

“Our pricing of [customer] contracts and our reserves for warranty and replacement are based upon our estimates of the life of our Energy Servers and their components, including assumptions regarding improvements in useful life that may fail to materialize. We do not have a long history with a large number of field deployments, and our estimates may prove to be incorrect.” [Pg. 70]

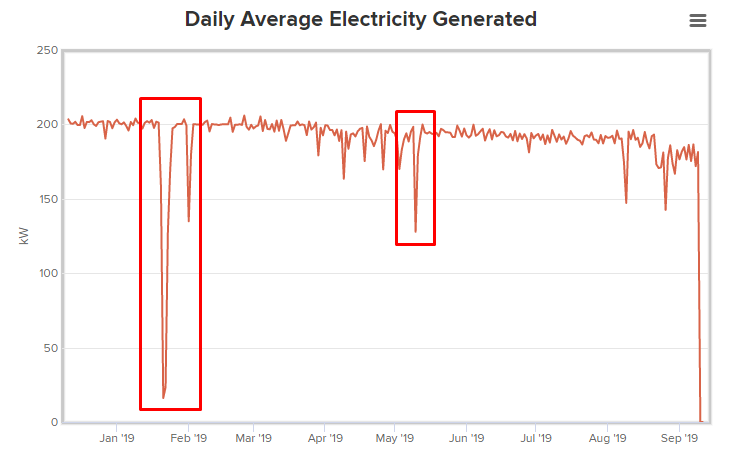

Finally, our field research corroborates that Bloom’s servers have experienced trouble in the real world.

We contacted several businesses to learn about the reliability of Bloom’s new systems. A Home Depot in Greenbush, NY, told us that they had a system “blow” within a year of having it installed. New York utility records show that the system was new, operating since December 2018. They also appear to show sharp drop-offs in electricity generated, consistent with what we were told.

We were told that another Home Depot, in Clifton Park, NY, [operating since September 2018] had its server come right off the building shortly after its installation, according to the same conversation. (We share more details on this conversation, as well as conversations with other customers and experts, in Part IV of this report.)

In short, Bloom’s expected server life is untested at best, and its history has demonstrated a 4-7 year lifespan.

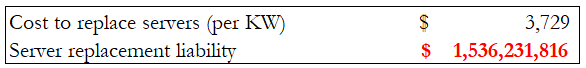

Even if we assume just 1 server replacement on an average outstanding contract life of 13 years, we estimate this to result in a nearly $1.5 billion unrecorded servicing liability:

Bloom’s Undisclosed $2.2 Billion Liability by The Numbers

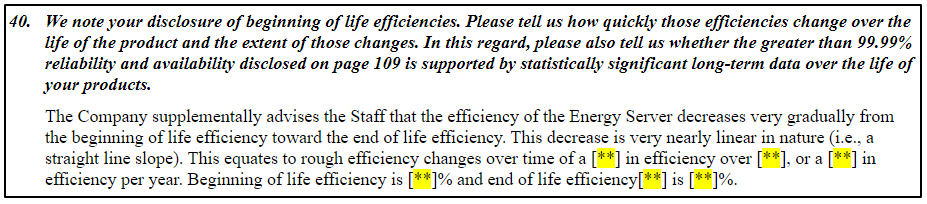

Bloom has been cagey about disclosing the actual life of its fuel cells/servers and other metrics that would make its servicing liability clear to the market. In SEC comment letters, the company redacts such information.

We have reached out to the company and asked what their estimate of servicing liabilities would be when factoring in the full length of their contracts and have not heard back as of this writing.

Below is our full breakdown of Bloom’s estimated undisclosed servicing liabilities, net of expected servicing revenue during that same time frame. For the full breakdown of our data collection and methodology, see Appendix A at the end of this report:

Our overall view is that Bloom’s economics are reliant on unrealistic assumptions about the useful life of its products. These are massive unnoticed liabilities that we expect will lead to materially adverse consequences for the company in the immediate future.

In fact, we have already begun to see this issue rear its head. However, rather than recognizing the reality of these costs, a troubling pattern has emerged where Bloom’s costs have been masked by tricky accounting.

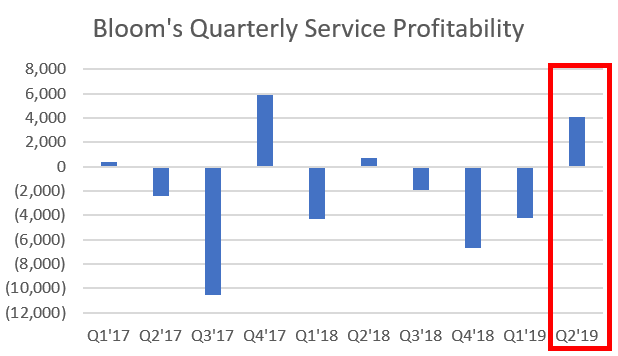

Servicing Liabilities Are Already Beginning to Show: Bloom’s Accounting Methods Masked Service Losses and Juked Revenue Numbers in the Recent Quarter

During the most recent quarter, Bloom disclosed it was commencing a project to “decommission” 18MW worth of servers in Delaware. The servers are only about 7 years old, yet the company is aiming to replace all of them.

As we know from Bloom’s service arrangements, the company is on the hook for the cost to replace servers. The company’s agreement on the project in question makes this crystal clear:

“Operator’s (i.e.: Bloom’s) responsibilities hereunder shall include, without limitation, promptly correcting any Bloom System or BOF malfunctions, either by (i) recalibrating or resetting the malfunctioning Bloom System or BOF, or (ii) repairing or replacing Bloom System or BOF components which are defective, damaged, worn or otherwise in need of replacement.” [Pg. 12]

One would think these unexpected server replacements would have represented a substantial hit to Bloom’s servicing profitability in the quarter. Instead, we see that the company reported one of its healthiest servicing margins to date. How could this be?

In poring over the disclosures about the server replacements, we find that rather than replacing the servers and taking the hit to servicing margins as we would expect, Bloom instead engaged in a complex transaction that seems to avoid recognizing any servicing losses at all.

Instead, the company claims to be “selling” new servers to the same project and BOOKING IT AS NEW REVENUE. [Pg. 35]

All told, we estimate the “decommissioning” transaction, net of supposed ‘new’ revenue, will represent over $135 million in losses and cash out the door for Bloom in coming quarters.

The transaction is clearly cash flow negative and will represent a near-term loss to Bloom, yet its complexities mask the significance and the timing of the cash outlays. These complexities include:

- $57.5 million to buy out equity in the project from one of Bloom’s financing partners [Pg. 33]

- Post upgrade, Bloom’s remaining financing partner will receive 100% of the revenues from the new servers and Bloom will receive none! This makes Bloom’s newly purchased ‘equity’ a seemingly worthless piece of paper. [Pg. 33]

- $40 million in cash collateral, posted by Bloom, to indemnify against up to $97.2 million in legal, regulatory, and tax liabilities.

- Presumably, the partner views the risks of these liabilities as material, given the high cash collateral, but Bloom has reserved nothing for them. [Pg. 34]

- $57.2 million in other liabilities, assumed by Bloom, that are vaguely contingent on Bloom’s stock price. [Pg. 34] [Pg. 23-F]

- $72.3 million, paid by Bloom, as a partial payment to “repurchase” its old servers. [Pg. 33]

Despite these significant cash outlays and assumption of liabilities, the decommissioning transaction created the appearance of positive top line growth. In the recent quarter, Bloom booked $91.7 million from the supposed ‘sales’ to replace its old servers, representing almost 40% of the revenue in the quarter. [Pg. 35]

This type of absurd transaction strikes us as textbook financial engineering. We find it incredibly suspicious that, despite the transaction affecting numerous income statement items, it looks to have avoided impacting ‘servicing’ items entirely.

Bloom’s Accounting Methods Mask Service Losses and Juke Revenue Numbers: Part Two

This is not the first time Bloom has employed this type of accounting alchemy.

In Bloom’s IPO prospectus, it disclosed replacing 172 early generation servers in 2016 [Pg. 66]. Once again, Bloom recorded the server replacements as NEW sales and classified cash outlays as investments instead of taking a servicing loss.

Bloom achieved this by determining that the server replacements involved such significant renegotiation of its old leases that it actually constituted a termination of the lease. We believe this, in turn, conveniently allowed them to book substantial write-downs in the pre-IPO period (where investors couldn’t see the write-down) while booking new revenue that improved the financials disclosed publicly in the IPO.

“Since the underlying assets under the arrangement were replaced (i.e., new generation Energy Servers were installed in place of the decommissioned older generation Energy Servers), the decommissioning of Energy Servers under the program did not constitute a lease modification, and was accounted for as a lease termination. Through December 31, 2017, the Company has replaced 196 Energy Servers with new generation Energy Servers sold as part of a new sales arrangement.” [Prospectus F-39]

“During 2015, the Company recorded a reduction in product revenue totaling $41.8 million for the decommissioning of its PPA I Energy Servers.” [Prospectus F-39]

“In 2016 and 2017, 172 and 0 respectively, of our acceptances achieved were for Energy Servers that were sold to existing customers under our PPA I decommissioning program.” [Prospectus 66]

We find it incredibly alarming that Bloom seems to be engaging in transactions that avoid recognizing servicing losses in a forthright manner that is transparent to investors—or in some cases, recognizing them at all.

The Edge of the Cliff: Why We Think These Servicing Issues are An Imminent Problem

We believe that this absurd juggling act is coming to an end and will culminate in an erosion of the company’s remaining cash over the next 6-12 months.

For starters, the company isn’t done replacing outdated servers and has acknowledged that it needs to secure $92 million in financing to finish the latest batch of replacements [Pg. 32]

We have also begun to see a slew of ‘one time’ charges and write-downs that we fully expect will continue in relation to upcoming server replacements. From the recent quarter alone [Pg. 35]:

- “We had repurchased and written-off 10.0 megawatts of our earlier generation energy servers for $25.6 million”

- “We recognized charges related to the decommissioning of PPA II Energy Servers of $8.1 million”

- “Additionally, in paying-off the outstanding debt and interest of PPA II amounting to $77.7 million, we incurred a debt payoff make-whole penalty of $5.9 million”

- “We had PPA II debt issuance costs written-off of $1.0 million and additional interest expense incurred for PPA 2 debt payoff of $0.1 million”

Finally, we took the current efficiency of Bloom’s California and New York projects, roughly 200 in all, and found that almost 15% of its projects likely need imminent fuel cell replacements, with almost 40% needing replacements within an estimated 14 months.

Extrapolating this data out, we estimate a $55 million imminent replacement liability with another estimated $147 million replacement liability over the next 14 months. Once again, this is just relating to fuel cell liabilities and does not include additional server replacement liabilities.

The Edge of the Cliff: Bloom’s Servicing Liabilities Had Historically Been Masked by Strong Revenue Growth. That Growth Is Now Gone

The reason Bloom’s issues are now bubbling to the surface is a lack of new revenue.

The company’s revenue model is heavily ‘front-loaded’. When the company sells a new fuel cell system, it collects 3 forms of revenue immediately:

- Product revenue (for the physical fuel cell systems)

- Installation revenue

- The first year of service revenue in advance. [Pg. 61] (Bloom also usually gets another 1-2 years of servicing revenue before needing to replace systems, giving it up to 3 years of front-loaded servicing revenue.)

After this jolt of initial revenue, Bloom collects a small ongoing annual servicing fee, but is required to carry the burden of all servicing liabilities.

The company has reported strong historical revenue growth, which has allowed its servicing liabilities to appear small relative to the influx of new money.

As mentioned earlier, Bloom acknowledged that it expects no revenue growth in 2020. The tide has gone out. Without new revenue, we expect the replacement liabilities to quickly represent larger and larger proportions of Bloom’s cost structure.

All told, we see a significant deterioration in Bloom’s cash balance and net income over the next year. With a large chunk of debt coming due by the end of 2020, we simply don’t see a silver lining here.

Part II: Bloom Energy is a Carbon Polluter and a Hazardous Waste Producer Masquerading as a Clean Energy Company

Putting aside economic sustainability, one of the biggest misconceptions about Bloom Energy is the idea that the company is providing clean, green and/or renewable energy. As we’ll lay out now in detail, this argument is severely misguided at best and deceptive at worst.

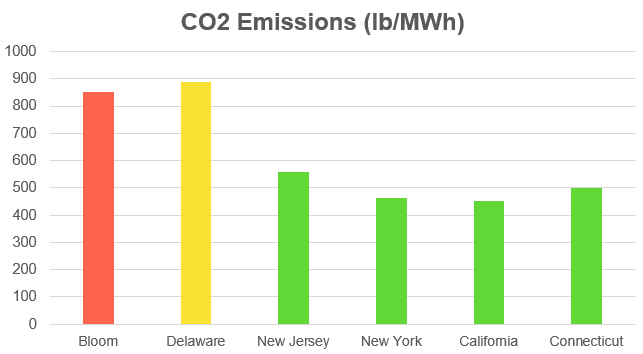

Bloom and its customers have consumed over a billion dollars in federal, state, and municipal clean energy subsidies, yet Bloom emits more CO2 than the grid in key states it operates. In fact, our findings show that the amount of CO2 Bloom Energy servers release into the air is comparable to modern natural gas power plants.

Corporations and governments have begun to wise up to Bloom’s claims on the environmental benefits of its products. Santa Clara California has essentially banned new Bloom Energy natural gas installations through recent legislation. New Jersey pulled the rug on subsidies to Bloom and other fuel cell providers. [Pg. 16] California is ending its program that subsidizes fuel cell manufacturers. [1,2,3]

Would Bloom be alive today without receiving over $1 billion in subsidies based on misconceptions around its product? Experts we spoke with, as we will detail later in this piece, believe the answer to this question is “no”.

Bloom Produces Significantly MORE Emissions Than the Grid in Most States in Which It Operates

We compiled the average CO2 grid emissions in the states where Bloom primarily operates. The majority of Bloom’s domestic deployments are in just 5 states (California, New York, Connecticut, New Jersey & Delaware).

As can be seen in the chart below, Bloom is far dirtier than most of the states it operates in. In Delaware, a state that is powered 98.6% by fossil fuels such as gas, coal, and oil, Bloom is only marginally better:

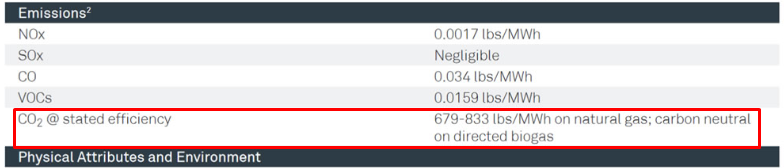

Bloom Falsely Claims That Its Servers Running on Natural Gas Produce 50% Less Emissions than the U.S. Electric Grid

Bloom claimed in its prospectus:

“When running on natural gas, compared to average emissions across the U.S. grid, Bloom Energy Servers reduce carbon emissions by over 50%.” [Prospectus Pg. 4]

This statement appears to be outright false, and by a wide margin. According to the latest official figures from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA), the U.S. grid emits 1,009 lbs/MWh of CO2.

Bloom’s own marketing documents show that its servers produce 679-883 lbs/MWh of CO2, a 12.5% to 32% reduction from the grid average.

Our own review of 205 Bloom projects in New York and California showed that they are producing an average of 835 lbs/MWh of CO2, a reduction of about 17.2% from the grid.

Bloom’s Carbon Emissions: Comparable to Those of a Modern Natural Gas Power Plant

Not only do we believe Bloom’s statements about emissions relative to the grid to be outright false, but comparing Bloom with “the grid” is the wrong comparison in the first place. The grid is dirty and old. Coal accounts for about 75 percent of the grid’s greenhouse gas emissions and the average U.S. coal power plant is over 40 years old.

A proper comparison would be between a new natural gas-operated Bloom system and a modern natural gas power plant. Using data from the U.S. Department of Energy, we plotted data from Bloom’s new generation systems relative to the average for a modern combined cycle natural gas power plant.

The numbers are comparable. Bloom’s newest generation systems emit roughly 839 lbs/CO2 per MWh on average versus a modern natural gas plant that produces 896 lbs/CO2 per mWh. [Pg. 18] The average across all 205 Bloom outstanding projects in New York and California was also comparable at ~835 lbs/CO2 per MWh.

Note that as Bloom’s systems age and efficiency goes down, they produce more CO2. (See the appendix for the inverse relationship between efficiency and emissions.) According to the data we reviewed, after only about 24 months, Bloom’s systems will produce CO2 levels on par with modern combined cycle natural gas plants (and then perform worse thereafter).

Bloom Also Wrongly Compares Its Emissions to the “Marginal Grid” (We’ll Explain), Painting Another False Picture of Its Emissions

Bloom has deflected questions on its emissions by attempting to compare itself to the “marginal grid” rather than the actual electric grid. So, what is the difference?

There are 2 types of power that feed the grid: baseload power and peak power.

- Baseload power is the type of power that is meant to meet the normal demands of the grid and is simply not easy to shut on or off. (An example is a nuclear plant which takes significant time to “shut off” once a nuclear chain reaction is commenced.)

- Peak power (“marginal grid”) is the type of power that is turned on or off during periods of peak usage (such as during the dead of winter when people are using a lot of heat). Peak power tends to be far dirtier because of the inefficiencies introduced by starting and stopping the generation process. When the term “marginal grid” is used, it typically refers to peak power sources.

Bloom is clearly baseload power—after all, the first thing the company’s marketing documents tout is how it is “always on”:

This doesn’t seem to be by choice. Multiple experts we spoke with noted that Bloom’s solid oxide fuel cells run into major issues if they are not “always on”. As we’ve noted, the systems operate at temperatures of 800C (or 1400F), and higher. If shut off, the drop in temperature can crack and break the ceramics and materials in the fuel cells.

Nonetheless, Bloom has repeatedly, and wrongly, compared itself to the very dirty “marginal” peak power sources, which make its technology seem cleaner on a relative basis.

We saw this in a recent interview with Bloom CEO KR Sridhar that aired in early September 2019. When an NBC Bay Area anchor questions Bloom’s emissions relative to the grid, Sridhar responds:

“…we are lower in carbon footprint than the marginal grid, even in a state like California which is very clean…”

This statement is technically true, but in the most incorrect way possible.

As shown in the earlier chart, Bloom’s systems are about 59% DIRTIER than the grid in California when you don’t slip the word “marginal” into the sentence.

Bloom used the same type of ‘marginal’ misdirection when it was fighting regulations in Santa Clara California that sought to curb new carbon emissions. Santa Clara rightly rejected the argument. (See an article on the subject here or view the city council meeting video at the 3:20:35 mark.)

Santa Clara, California: We Are Moving Toward Fully Renewable Energy

Bloom’s Response: This is a De Facto BAN on our Product

The fight between Bloom and Santa Clara serves as an example of Bloom outright rejecting renewables.

On May 7, 2019, the Santa Clara City Council required that new fuel cell projects in Santa Clara use renewable biogas. This was effectively viewed as a “ban” of Bloom Energy, as the company was forced to concede that the requirement to use biogas meant that Bloom Energy Servers were infeasible. From Bloom’s own petition:

“…the Resolution effectively bars residents and businesses in Santa Clara from installing Petitioner’s fuel cells unless the fuel cells are powered by renewable fuels sourced solely from within the State. It is infeasible, however, to satisfy this condition because renewable biogas sourced solely from within the State is virtually non?existent as a reliable fuel source or prohibitively expensive for a commercial user.”

Rather than committing to move toward renewables, Bloom instead enlisted high-powered law firms to engage in aggressive lobbying and ultimately litigation in an effort to get Santa Clara to change course from renewables.

Bloom Servers Accumulate Hazardous Waste, Including Cancer-Causing Benzene

It turns out CO2 isn’t the only byproduct of Bloom’s systems.

In July 2018, Bloom disclosed that the EPA was seeking to collect $1m in fines from the company related to its disposal of benzene, which is hazardous waste found in Bloom’s desulfurization containers. [Pg. 36] The company stated in its prospectus that it was contesting the fine, and does not anticipate ‘significant’ additional costs or risks from compliance with the latest guidance on hazardous waste disposal.

The Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS) has determined that benzene causes cancer. Long-term exposure to high levels of benzene in the air can cause leukemia, cancer of the blood-forming organs.

Bloom’s S-1 from July 2018 seems to play down its exposure to benzene:

“… natural gas, which is the primary fuel used in our Energy Servers, contains benzene, which is classified as a hazardous waste if it exceeds 0.5 milligrams (mg) per liter. A small amount of benzene (equivalent to what is present in one gallon of gasoline in an automobile fuel tank which is exempt from federal regulation) found in the public pipeline natural gas is collected by gas cleaning units contained in our Energy Servers and is typically replaced once every 18 to 24 months by us from customers’ sites.”

The above clever wording describes the relatively low levels of benzene found in natural gas. What is not clearly conveyed, however, is that Bloom’s servers collect these small amounts of benzene over long periods, eventually resulting in large quantities of the hazardous waste.

Bloom Has Been Sued for Allegedly Dumping Benzene in California Landfills. Court Documents Show Bloom Labeled Itself a “Large Quantity Generator of Hazardous Waste”

In 2016, corporate waste management company Unicat Services sued Bloom, alleging breach of contract. Unicat had been hired to clean and dispose of Bloom’s waste canisters in public landfills but discovered that the canisters contained “extremely hazardous” and “toxic” material. In the lawsuit, Unicat alleged that Bloom had been dumping benzene into the ground in California instead of disposing of it properly.

For a company that has built its reputation on claims of being environmentally friendly, this lawsuit essentially alleges that Bloom doesn’t care about the environment. From the complaint:

“Unicat Services was told [by Bloom] that Bloom Energy had the contents of the fuel cell canisters emptied, canisters cleaned, and the extracted contents sent to public landfills for non?hazardous waste in Mexico and California. Unicat Services planned on doing the same operation in Alvin, Texas…”

“Bloom Energy had effectively represented in 2013 that all of the canister contents was nonhazardous and could be dumped at any public landfill (the process Bloom Energy told Unicat Services was being done in California and Mexico).”

“As it has been trained by Bloom Energy, Unicat Services planned on emptying the canister contents into the nearby roll?off box and to transport the same to a public landfill as represented had been done in Mexico and California. However, prior to taking the shipment to a public landfill, [Unicat] as a matter of professionalism and best?practices, decided to test the contents—just to be sure that it was safe to take to a public landfill. Their tests revealed that the Bloom Energy fuel cell canisters that Bloom Energy had transported to Unicat Services (and, according to Bloom Energy, had been previously emptied in Mexico and California and dumped in public landfills) contained an extremely hazardous and toxic material – benzene, which can cause blood cancers under long exposures, and which is a material clearly classified as hazardous by federal and state environmental authorities.“

The complaint showed that rather than rewarding Unicat for helping correct a major environmental issue, Bloom tried to use it as leverage against Unicat:

“Unicat Services would have thought that an advertised “green” company like Bloom Energy would have rewarded Unicat Services for bringing to Bloom Energy’s attention the hazardous waste in Bloom Energy’s fuel cell canisters so that Bloom Energy would not expose the environment and people to dangerous toxins.“

“Instead of rewarding Unicat Services for flagging the benzene to Bloom Energy, Bloom Energy used this as a renegotiating hammer to lower the per canister price that Unicat Services could charge…”

Appended to the court documents were exhibits that confirm that Bloom is, in fact, collecting large quantities of hazardous waste.

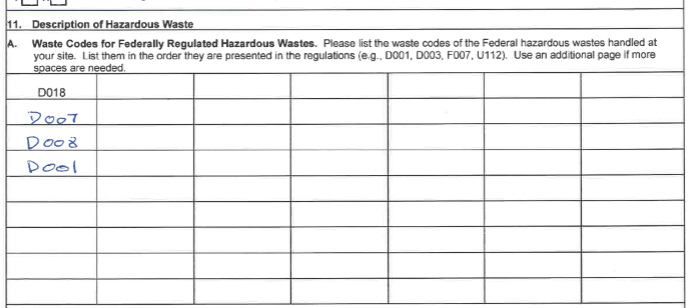

For example, in signed court exhibits for Bloom Energy filed with the EPA, the company calls itself a “Large Quantity Generator” of hazardous or industrial waste.

The waste Bloom generates falls under 4 EPA codes (D018, D007, D008, D001) which, according to the EPA hazardous waste codes, represent “Benzene”, “Chromium”, “Lead”, and “Ignitable waste”, respectively.

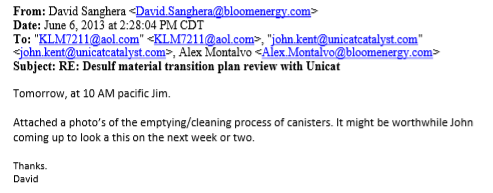

Attached to those same court documents, per an e-mail from a Bloom Energy employee, are photographs of the “emptying/cleaning process of canisters”.

The employees undertaking the “emptying/cleaning process” are handling 55-gallon drums wearing what appear to be respirators.

The lawsuit was settled confidentially.

This hazardous waste generation seems to be starkly at odds with Bloom’s public image. For example, in Bloom’s marketing video touting its relationship with the city of Hartford, Connecticut, it refers to its technology as “clean, reliable power without pollutants.”

Here’s our simple thought: before Bloom or Bloom customers receive any more government subsidies, we urge authorities to investigate the allegedly illegal toxic benzene dumping by the company.

Bloom Has Consumed $1.1+ Billion in Subsidies, Often Under Questionable Pretenses. Now, Jurisdictions Have Pulled the Subsidy Rug Out from Under the Company

As noted earlier, Bloom has consumed over $1.1 billion in subsidies on the Federal, state, and local level, often under the incorrect auspices of being green, clean and/or renewable.

The company’s subsidies in California and New Jersey were curtailed after the states determined they were not contributing to green energy goals.

(For a detailed state-by-state breakdown of Bloom’s subsidies see Appendix B.)

Delaware: Bloom Sold Us a Bill of Goods

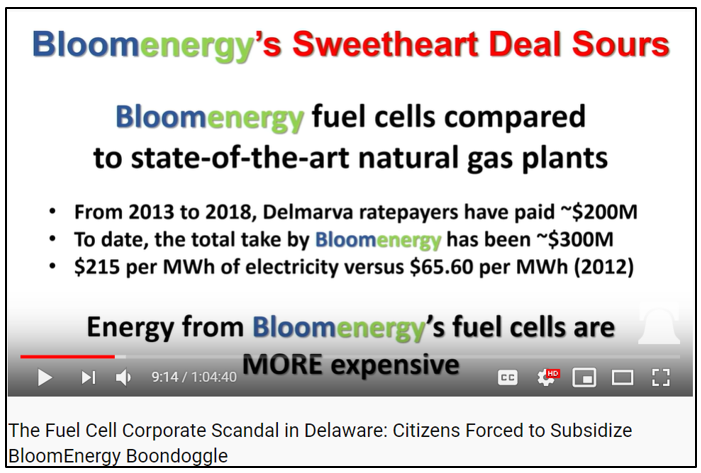

In Delaware, the state and its residents have largely had a case of ‘buyer’s remorse‘ after forking over $221 million (and counting) to Bloom in the form of grants and subsidies.

After a lobbying effort by the company, Delaware changed legislation so that Bloom’s natural gas systems could be considered “renewable energy”. The state has since come under much criticism for the subsidy, with Delaware State Senator David Lawson declaring:

“I think we were sold a bill of goods.”

The Heritage Foundation documented the Delaware “Bloom Energy Boondoggle” in thorough detail in this hour long presentation:

Bloom Has Complained That Green Energy Regulations Are Threatening Its Business and Subsidies

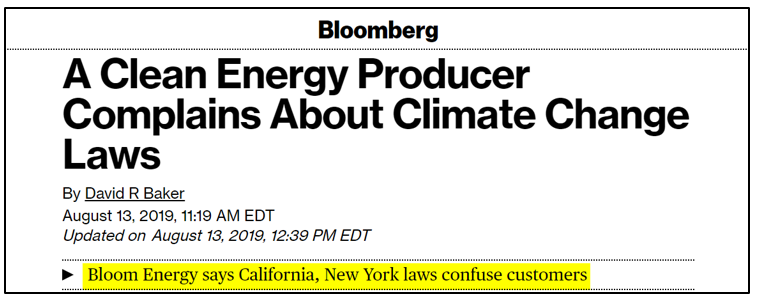

Bloom has recently made it even clearer that it should never receive subsidies under the auspices of being “green”. On Bloom’s most recent conference call, CEO Sridhar said that green energy legislation in states like California and New York is creating “confusion” for its customers.

We disagree— the only confusion seems to have been the perception that Bloom’s natural gas-fueled systems were ever green in the first place.

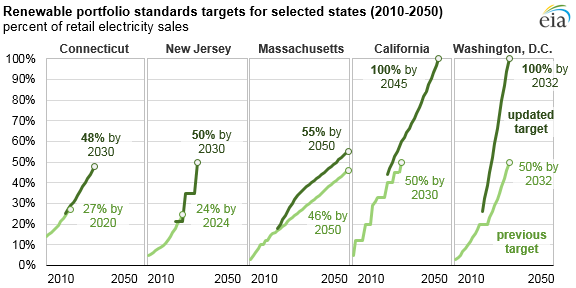

Contrary to Bloom’s complaint, the green legislation itself seems quite clear—states like New York, California, Connecticut, and New Jersey are moving toward renewable energy:

This creates an obvious problem for Bloom, because the vast majority of its generators simply aren’t renewable energy.

Customers Love “Greenwashing” With Bloom.

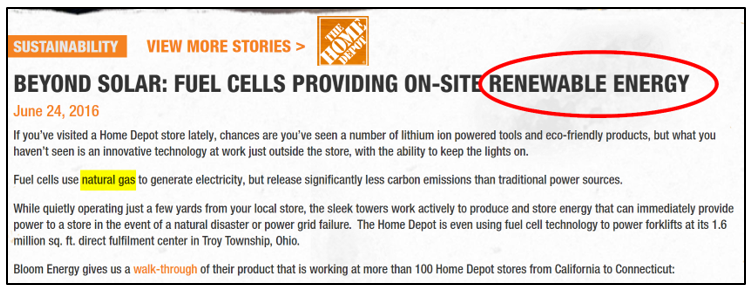

Home Depot: Bloom Provides Us “On-Site Renewable Energy”…Such As Natural Gas

We agree with Bloom on one thing: its customers do appear to be confused.

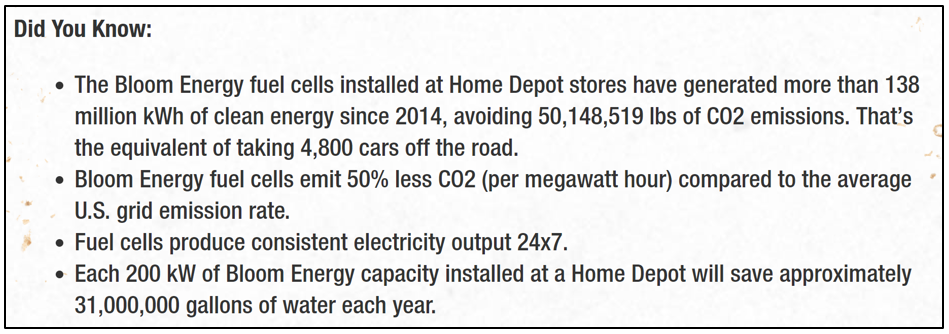

For example, when Home Depot made an announcement in 2016 that it was working with Bloom, it called it a “renewable” energy source with “significantly less carbon emissions than traditional power sources.”

Once again, natural gas is simply not renewable.

Home Depot also parroted Bloom’s false claim that it produces 50% less CO2 than the grid average. It then used this flawed metric to determine that installing Bloom’s systems had taken the equivalent of 4,800 cars off the road.

As we have shown earlier, Bloom is actually far DIRTIER than the grid in states like New York and Connecticut, where Home Depot installed many Bloom systems.

Unfortunately for Home Depot (and for the planet) it’s more likely that installing Bloom Energy Servers in clean states like New York and Connecticut added thousands of cars to the road.

This is the ultimate version of virtue signaling and greenwashing, and it’s all a result of what we believe to be a false narrative peddled by Bloom Energy.

AT&T: “Our Bloom Natural Gas Fuel Cells” Count as an “Alternative” Energy Source

Even though natural gas is hardly “alternative”, AT&T has counted its partnership with Bloom as moving toward its alternative energy goals on its website.

The renewable energy angle to the Bloom story is that its servers are capable of running on biogas, though Bloom itself admits that biogas is expensive, isn’t readily available enough, and is only used by a fraction of its customers.

Part III: Bloom Energy Executives Have a History of Making Allegedly False Statements

Beyond the questionable value of Bloom Energy’s technology and the dubious “clean energy” value proposition advanced by the company, we also see some red flags with the executive team.

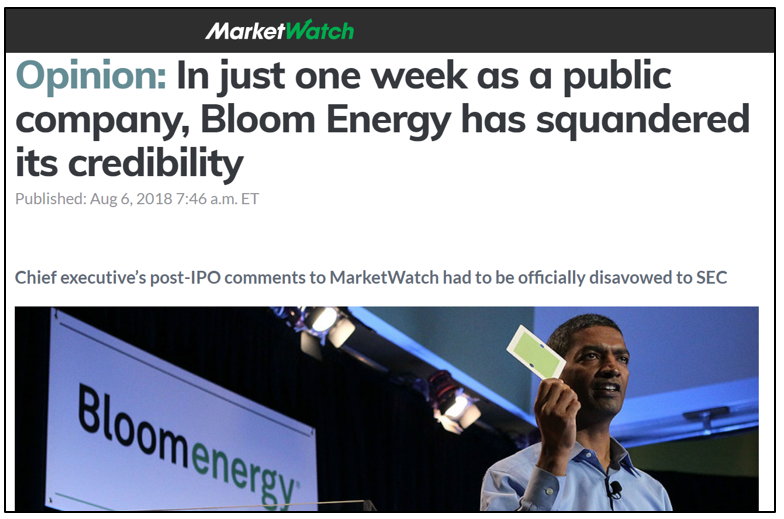

The Company was Forced to Correct False Statements Made by Its CEO on the Day of its IPO

In 2018, shortly after the company’s initial public offering, its Chief Executive Officer, KR Sridhar, had statements he made on the record “officially disavowed” after an interview with MarketWatch.

When he was initially asked on the day of Bloom’s IPO about the company’s profitability, Sridhar told three MarketWatch staffers that Bloom was “a profitable company as of [the second quarter],” and he expected that to continue going forward.

MarketWatch asked a follow-up question to clear up whether Sridhar meant GAAP terms, to which he answered “affirmatively”. MarketWatch then used those comments as the lead for a story published on July 26, 2018.

That statement turned out to be extremely incorrect:

Following the piece, MarketWatch was quickly contacted by a spokesperson for Bloom Energy with a “clarification”. The company explained to MarketWatch that Bloom expected to be GAAP profitable only on an operating basis, but not on a net basis.

But it turns out that wasn’t true either.

MarketWatch updated its story, but even then, the clarification – in addition to the original statements – were deemed misleading.

Bloom Energy followed the clarification by making another clarification, this time a filing with the Securities and Exchange Commission itemizing its CEO’s misstatements and correcting them one by one.

MarketWatch then followed up with another piece summarizing its view of the experience:

Bloom Paid $16.7 Million to Settle Allegations That It Lied to Its Brokers, Leading to Their SEC Sanctioning

In 2009, brokerage firm Advanced Equities raised approximately $122M from 609 investors at a $1.45 billion valuation for Bloom Energy. During the fundraising process, Advanced Equities allegedly made several misstatements about Bloom Energy.

Advanced Equities and its founders were sued by the SEC in 2012 for those misstatements. The firm placed the blame on Bloom, claiming the company had “misled them and caused them to get sanctioned by the SEC.”

The SEC lawsuit against Advanced Equities alleged a series of bald-faced lies and fabricated documents, including that:

- “[Advanced Equities] misstated that [Bloom’s] projected revenue of $2 billion “is currently under contract and backordered”. In reality, [Bloom] only had between $10m and $42m (10 to 42 individual hardware units) under contract as order backlog at that time.”

- “…also misstated that [Bloom’s] CEO had shown [Advanced Equities] emails with a “$2 billion order from the CIA, which is not even in [Bloom’s] numbers.” In reality, [Bloom] did not have any order or other agreement from the CIA for any dollar amount at that time.”

- “[Advanced Equities] misstated again that [Bloom] was “getting $300m from the Department of Energy” when in reality, [Bloom] had not yet received any funding from the Department of Energy and had only applied for a $96.8 million loan.”

According to a July 2018 Wall Street Journal article, founders of Advanced Equities had “threatened to sue Bloom, claiming that [Bloom] representatives were the sources of false information…”.

At the time, Bloom Energy denied those allegations but still settled with the founders of Advanced Equities, recording a $16.7M charge, according to documents reviewed by the Wall Street Journal.

Co-founder of Advanced Equities, Dwight Badger, told the Wall Street Journal in 2018:

“I am currently under a confidentiality agreement… and [Bloom] is currently seeking to prevent me from releasing the information I have and claiming I breached the agreement, a charge I deny.”

Part IV: Experts, Customers and Competitors Reveal the Boring Truth About Bloom’s Technology

In preparing this piece, we spoke with dozens of people including experts in the fuel cell industry, Bloom customers, competitors and former employees.

Our discussions indicate that Bloom’s technology is already well-understood, “pretty old”, and still faces two major hurdles: cost and durability.

19 Year Fuel Cell Expert: Bloom’s Technology “Hurts the Fuel Cell Industry” and “Public Image (of Fuel Cells) Overall”

One of the very first conversations we had was with a technician with 19 years of experience in the fuel-cell industry who has worked with everything from low temperature, low pressure hydrogen air/hydrogen oxygen PEM fuel cells to high pressure hydrogen oxygen aerospace-based fuel cells. His resume indicated a broad range of knowledge, from simple testing to advanced lead design for aerospace applications.

We approached him as objectively as possible, letting him know we wanted to hear both the good and the bad about the industry. When asked about Bloom Energy’s contribution to the fuel cell space he didn’t hold back his immediate distaste; his first response was a long sigh.

“Not very excited about Bloom Energy,” he muttered, sounding disappointed. “My opinion on Bloom Energy is that they may have gotten out a little father ahead of themselves than they should have. Perhaps [they should have] spent a little more time in research and gotten a better handle on what they were wanting to do before they started bringing it to market.”

He continued:

“I feel like the general perception of Bloom Energy is that they kind of hurt the fuel cell industry as a whole.”

When we asked why he thought they were hurting the industry, he responded:

“…they went out and made some pretty big bold claims, which would have been awesome if it had been 100% accurate, but it’s looking like now that they made some claims and got some money for some ideas that looked good on paper, and didn’t necessarily have a lot of credence to it. So, in my opinion, when you do that with the general public – when you promise them the moon, you better hit the moon. Whenever you make big bold claims, you better be able to follow them up – especially with something such as a temperamental R&D type subject as fuel cells. You only get the one shot and whenever you don’t deliver, people aren’t super forgiving whenever you invest a lot of money and don’t deliver on everything you said. In short, my opinion is that they may have overstepped, and it is hurting the fuel cell public image overall.”

Speaking about Bloom’s push to raise money:

“They were just making it very ‘oh yeah, this is great, it’s going to work, it’s no questions’. I understand why they did it, but at the same time you can’t go to the public and say this is going great, this is going to work and not address the nuances…”

He also told us he thought Bloom had made these bold claims simply to raise money:

“For money. For the money. It’s my understanding they had tons of money coming in from capitalists that were interested in – it’s kinda like, what is that show, Shark Tank? You go out and you make the pitch and if you make the pitch well enough; they’re going to give money to you. If you don’t make the pitch well enough, it’s not so much. So, they were forced into making those kinds of bold claims to get the money.”

The technician continued, telling us again how he thought this was bad for the industry as a whole:

“The problem is when you make those bold claims and then you can’t deliver, it really turns everything sour. And it’d be one thing if it were just the investors, but they made it so public and so widespread, that’s where I feel the disservice to the general industry was. I’ve talked to multiple people that were not involved with fuel cells at all and you mention fuel cells and they’re like, ‘Ah, I don’t know about that’. ‘You remember about 4-5 years ago Bloom Energy?’. ‘Bloom Energy, yeah I remember that. Did that work? Didn’t that fall through or something?’ That’s not the image that the fuel cell industry needs.”

Finally, we asked his opinion on whether or not Bloom was ahead of the rest of the industry. He responded:

“No, I don’t think so. I think Bloom Energy is only recognizable by name. I think your Ballard, your Plug Power, those are more industry leaders. They have more equipment out there. They’re more involved with both the automotive and stationary applications. I think – and they’re keeping a lower public profile until they can go and get a lot of good solid data. They actually have quite a few busses up and running on fuel cells.”

“I really think Bloom just made the misstep of going too public, too fast and not having the ‘ooh’ and ‘ahh’ factor to maintain that approach,” he concluded.”

14-Year Fuel Cell Expert in Performance Analysis: “They Use the Traditional Classic Materials”

We also contacted another expert with 14 years of experience working in fuel cells and fuel cell performance analysis, who holds a B.S., M.S., and a PhD in Chemical Engineering. We asked him if he thought Bloom had any intellectual property that puts them ahead of new SOFC entrants. He responded:

“No, I don’t think so. These material developments are very real, very complicated and very fundamental. So, in SOFC, we’ve made it better compared to 10 years ago. But I don’t think there is revolutionary material [in Bloom’s products]. Based on most of the disclosures, they’re using the traditional materials. It’s used in other fuel cells. They use the traditional classic materials.”

We also asked about whether he thought the company’s marketing was accurate. He told us:

“I see in some news they said they have 5 year stacks. My guess is they may have 2.5 or 3 year stacks. In that range. They probably have 50% [efficiency] they can reach for 3 years.”

“Based on their quarterly report, their cost is still much higher than other fuel cells. It’s almost double in terms of cost. So that makes the electricity very high per kilowatt hour. I would say, probably triple the electricity of the classic generation. I would estimate their cost is probably 30 cents per kilowatt hour, based on my estimation and their costs.”

Finally, we asked if he thought Bloom could operate consistently and profitably without government incentives. He concluded:

“That is very hard for all the fuel cells now. It’s not easy.”

PhD in Mechanical Engineering and Fuel Cell Expert: Fuel Cells Only Have a “50/50 Chance of Making It Long Term”

We also reached out to a U.S.-based PhD in mechanical engineering with research experience assessing the life cycle environmental impact of SOFC systems using energy systems modeling.

We asked for his take on whether or not fuel cells could make it in the long term and he was less than confident in his response. He also brought up durability and cost:

“I’d personally like to give you a different answer, but I think based on the competition I’m seeing from renewables and just conventional technologies, that I think fuel cells have a 50/50 chance making it long term. Again, the issues being lifetime and cost. The thing with lifetime is not only do you have to go through the maintenance part of it, but when you replace a stack you’re basically paying for a whole new stack. So, lifetime and cost are also very much intertwined.”

“When it comes to the market, it also comes down to the cost. And I’d say even more specifically to the lifecycle cost. So, there’s a capital cost, right? And that’s how much a system will cost up front. But then there’s a lifecycle cost which includes not only the capital cost, which is that initial cost that you pay for the system, but it also includes the fuel cost, it also includes the cost to replace stacks over the lifetime. And so it’s the lifecycle cost that I’ve seen that is just not competitive at this point. It’s much higher than internal combustion engines and microturbines.”

He continued, going into more detail on cost and calling into question what he thought about Bloom’s costs versus what the Department of Energy is targeting. The numbers he used were almost a decade old, but we thought the delta between Bloom’s cost versus the DOE target was still worth noting:

“There’s very little information on Bloom’s costs that’s been made public. There was one article published in 2010. Things have probably changed since then. There was a cost that Bloom had released.”

“For a 100 kW Bloom energy system, it would cost $700,000 to $800,000. So the cost, if I just do the math. That is $7000 to $8000 per kilowatt. So it’s about $7500 per kilowatt for a Bloom Energy system. That’s in 2010. And DOE’s target is closer to $900 per kW.”

PhD and Fuel Cell Technology Graduate Professor: Bloom’s SOFCs Are “Pretty Old Technology”

We also reached out to a PhD Professor of Engineering who teaches a graduate course in fuel cell technology and studied materials for solid oxide fuel cells for his graduate degree.

We asked him how fuel cells would rank among other green technology in the line for mainstream adoption. He told us:

“In terms of overall green energy, probably what’s best for the environment and sustainable are wind and solar…”

He also brought up SOFC’s high temperatures as one of their key disadvantages:

“The main disadvantage with the solid oxide fuel cell is the high operating temperature. They’re operating at around 700-800 degrees Celsius.”

When we inquired as to how likely he thought it was that Bloom had something extremely unique with their patents, process or catalyst, he responded:

“Their technology is pretty old technology. It’s very well established.”

He also pointed to the main hang-ups in the solid oxide fuel cell industry as costs and manufacturing.

“The science is solid. There isn’t anything thermodynamically that says that a fuel cell will not work. That technology exists. It’s just now how you manufacture such that you can deliver it in a low-cost way. I think that’s where the fuel cell industry is at. I think even Toyota still has to handmake some of their fuel cells. The components are not well suited for automation.”

Former Bloom Employee: “If Congress Didn’t Renew Their Subsidies, Bloom Energy Probably Wouldn’t Exist Today”

We also spoke to a former Bloom employee who worked for the company in the late 2000’s and has more than 15 years’ experience in servicing advanced energy products.

He first recalled being recruited saying:

“The reason I turned it down was because of the product. Fuel cells have been around forever. No one’s been able to crack the code to make it profitable. Here I am being recruited by a company that says otherwise.”

When we asked about whether Bloom had ‘cracked the code’ to get to profitability, the former employee focused on subsidies:

“I don’t know how you do that without subsidies and the materials that are in that thing are all rare earth materials which are pretty costly. There’s only a few countries in the world – I think it’s China and Russia – that own the rare earth materials that are being used in the thing. That’s my knowledge from 11 years ago. Things could have changed, but it just seems like it’s just so expensive to make and produce and then without the subsidies…

“…if congress didn’t renew their subsidies, Bloom Energy probably wouldn’t exist today. I just don’t know how you make that. It’s just playing off the green energy/climate change things that are going on out there that people want to feel good about this stuff and they’re buying these Bloom Energy boxes…”

He also talked about the company’s controversial project in Delaware:

“…the company was thrown a lifeline. They weren’t doing that well. You’ve got the Obama administration – I think it was Joe Biden put the onus on the people in that state to subsidize Bloom Energy. Bloom Energy made a bunch of promises about employees that they never kept. But the people in Delaware are still paying. It’s crazy.”

He also commented about companies using Bloom products strictly for their PR image:

“I think with Bloom Energy – like, Google and Apple and some of these firms, are like ‘yeah, I want to get on the bandwagon because I can make my stockholders happy because I’m doing something with green energy…’ A lot of green energy stuff that was going out there maybe didn’t work well, but these people were willing to take the risk and spend the money. Plus, they were getting subsidies so the pain wasn’t that great, either. They all jumped in and took the risk.”

We asked the same employee about the idea of companies using Bloom Boxes to claim that they’re using clean and green energy. He responded quickly:

“Well, they’re not really clean. They’re still putting out a bunch of carbon dioxide. Everybody’s complaining about CO2 and yet, that’s a byproduct of this. And over time it gets worse because the efficiency of that fuel cell doesn’t stay 100%.”

Bloom Customers Weigh In

We also wanted to speak to people that had firsthand experience with Bloom Energy servers. After identifying project sites where Bloom servers have been installed through NYSERDA records, we spent weeks calling and speaking to more than 40 locations where servers have been installed.

Some people that we spoke to at businesses like Home Depot and Walmart (store managers and assistant managers, mostly) told us that they didn’t really know much about the Bloom Boxes on site. Most of the managers said they didn’t notice anything out of the ordinary unless something went wrong. Several referred us to their corporate numbers, as the Bloom installations were corporate-led initiatives.

The managers indicated that Bloom does all the servicing and didn’t have prescheduled maintenance. They would see the service trucks come by from time to time but other than that generally had no knowledge of how regularly they were serviced or to what extent.

Several of the managers that we spoke to, like one at the Home Depot in Enfield, said that the energy boxes have helped their P&L, or that energy costs weren’t an issue. This was to be expected, due to Bloom guaranteeing service at dirt cheap – and we believe unsustainable – prices.

The issue of durability was brought up on a call that we had with a Home Depot manager in Greenbush, New York. As soon as we mentioned fuel cells to him, he launched into a story about how one had “blown” right after being installed and how another, at a second location in Clifton Park, “came off the building”.

The Home Depot manager said:

“We had it blow once already and we lost power for about a day and a half. There was a power surge and it blew. But other than that, it’s been quiet. You’d never notice it until something’s wrong with it. We’ve only had it for maybe a year now, going on maybe a year. A transformer blew on it.”

We asked him to confirm whether the issue was with the Bloom boxes or the conventional grid. He responded:

“It’s just hard when something does go wrong, you don’t know if it’s wrong with the power company or the fuel cell, so everybody’s gotta figure out who’s problem it is before they’ll fix it. It took longer to figure out who was responsible to fix it than getting it repaired.”

“It was the fuel cell. It was them.”

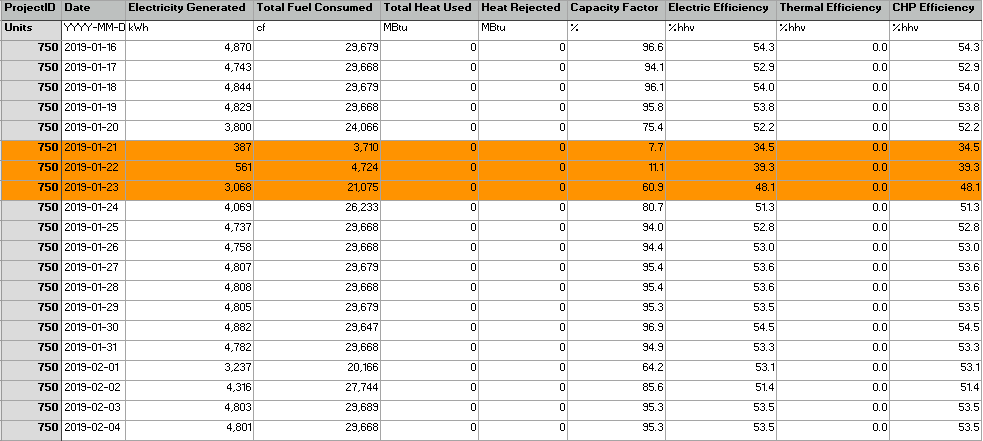

We were able to corroborate the claims by looking into the public NYSERDA data for Home Depot Greenbush, which shows an interruption in service in late January 2019. Efficiency numbers dropped across the board for a three-day period.

Finally, he offered up a story about another Home Depot store in Clifton Park that had installation issues that were eventually resolved:

“They didn’t use the right bolts and everything came off the building. They had to re-do it. They didn’t use the right bolts. They had it corrected by the time they got to our building. I guess there was an issue with the anchoring system.”

Conclusion: We Are Witnessing Another Falling Unicorn

All told, we believe that Bloom Energy is facing numerous material and imminent problems.

With the company’s accounting issues now exposed, we hope shareholders will demand far more detail going forward. We also hope the company’s various partners will be more vigilant in understanding the company’s carbon and hazardous waste footprint.

Bloom’s story arc strikes us as reminiscent of other fallen Silicon Valley unicorns:

- Lay out a grand vision to save the world

- Overpromise

- Draw accolades from everyone, raise billions of dollars

- ‘Fake it ‘til you make it’

- Never actually make it

Simply put: the problems with Bloom’s technology, accounting, undisclosed liabilities, debt burden, emissions & hazardous waste issues, in our opinion, put the prospect of bankruptcy or a reorganization on the table over the next 12-18 months.

Appendix A: Methodology & Data Collection—How to Replicate Our Work

Ideally, we want the company to respond to our questions and offer the market a full explanation of its economic liabilities, CO2 output, accounting practices and other key issues. We welcome a response from the company, but in the event that they do not respond, we also want readers to be able to fully replicate and understand our work.

This thesis required a lot of unique data collection and number crunching, so we view it as important that we detail our methodology for both gathering and processing the data to help readers understand how we arrived at assumptions and conclusions. We encourage readers to download, examine, and question these datasets and our approach themselves.

Starting with our estimate of Bloom’s servicing liabilities:

The data and assumptions that went into it:

- Cost to replace fuel cells: Bloom doesn’t disclose how much fuel cells cost relative to total product, but EPA research shows that fuel cells represent roughly 29.3% of the total cost of a server. [Pg. 114]. New Jersey research into fuel cell projects (including Bloom’s) show that the fuel cell servers cost roughly 2/3 more than the fuel cell itself. [Pg. 21] We used the EPA metric to estimate cost to replace fuel cell and applied this percentage to Bloom’s product cost per kW in the latest quarter: $3,045/kW [Pg. 47]. We used ONLY product cost for this calculation (rather than total installed system cost) because fuel cells can be “hot swapped” and therefore do not require incremental installation costs.

- Fuel cell life: This is based on our collection and extrapolation of Bloom’s new generation 5 servers from data in California and New York (more on this below).

- Current replacement cycle: We are currently mid-way through the replacement cycle. (In reality, we expect the company to replace many cells imminently, as shown by the current Generation 5 fuel cells nearing replacement thresholds, but we wanted to err on the side of conservative).

- Recovery value: We examined what the recovery value of fuel cell/server replacements could be. Department of Energy research has determined that recovery value for SOFC replacements “would not be significant” [Pg. 105]

- Total install base: The latest quarterly total install base was 412 mW per company financials [Pg. 70]

- Cost to replace servers: 70.7% (or 1-29.3%) of the company’s reported total installed system costs (TISC) per kW for the latest quarter; $5,274. (This assumed that fuel cells are not replaced along with the servers. If the cells must also be replaced the cost would be significantly higher.) We used TISC for this estimation because servers would require new installation, whereas fuel cells can simply be “hot swapped” and therefore would presume to only impact product costs rather than total installation costs.

- Fuel cell replacement liability: Based on the expected fuel cell life from field data tracked from New York & California, fuel cell cost, and length of time left on average contracts.

- Server replacement liability: All told, we assume 1 server replacement per average 13 year remaining contract life, given the company’s historic 4-7 year replacement rates.

- Service revenue: We extrapolated the latest quarterly service revenue run-rate across the 13-year average remaining life. [Pg. 48]

Raw Data Sets on Output and Efficiency of Bloom’s Projects

Monthly performance data was obtained in two states, New York and California. These are the only states we could identify with robust and regularly-updated data on energy systems.

California’s Self-Generation Incentive Program (SGIP) publishes performance data on its website. See Monthly PBI Performance Report under Number 9 here.

New York has a similar program. The New York State Energy Research and Development Authority, known as NYSERDA publishes Distributed Energy Resources (DER) data on projects they fund. To see Bloom generators in field we searched “bloom energy” in the installer/developer section here.

To get a sense for how Bloom’s newest version of generators performed, the analysis focuses on generators that were installed post 2016. We did this because Bloom stated that it expects 5-year performance from its fuel cell lives from 2017 onward and we wanted to test this specific claim:

“Time to stack replacement primarily driven by our fuel cell stack lives in the early years, replacement was typically 12 to 18 months. Over the years we have made steady improvements in our fuel cell lives, and from 2017 onwards we expect to average over five years between replacements.” [IPO Prospectus Pg. 61]

To isolate generators installed after 2016, the “interconnection date” in SGIP data and the first month of generation in the NY data was used in the data set.

There were some instances where generators exhibited strange performance in the data (such as generators operating at below 40% efficiency or seeming to break). With the efficiency, output and emissions samples we attempted to scrub out data points that appeared to be mostly negative outliers in order to give Bloom the benefit of the doubt (such as generators beginning to operate significantly below or above standard LHV efficiency between 40% to 70%, then sharply reverting). Had we included these potential outliers, Bloom’s performance would have likely been significantly worse.

Higher Heating Value to Lower Heating Value Efficiency Conversion

A multiple of 1.107 (see page F-1) was used to convert the higher heating value efficiency provided by NYSDER to the lower heating value efficiency Bloom uses on its guarantees. This is the conversion factor found in Bloom’s contracts with customers.

Emissions: Pounds of CO2 per MwH

To calculate pounds of carbon dioxide per megawatt hour emissions the following formula was used

(3.412 MMBtu / 1 MWH) / HHV Efficiency * (117 pounds of CO2 / 1 MMBtu) = x bls carbon dioxide / MWH

- 1 MWH is equivalent to 3.412 MMBTU. This is the conversion factor Bloom uses in its contracts (page F-1)

- 1 MMBtu unit = 117 lbs of CO2 see Natural Gas row from the Energy Information Administration here

- Heat rate = (ideal heat rate)/efficiency = (3412 Btu/kWh)/efficiency

Fuel Cell Replacement Threshold

Bloom appears to be replacing fuel cells between 50% and 48% LVH efficiency. Fuel cells degrade linearly over time, yet between these efficiency ranges across Bloom’s project base we regularly see sustained spikes in efficiency. The reason inferred for this is because fuel cells are being replaced in order to hit efficiency targets.

The largest source of historical data obtained on Bloom generator’s past operating performance is from the state of California’s SGIP program. Of the over 10,000 performance months dating back to 2012 in the SGIP data (each representing a historical month of operating performance from a Bloom generator dating back to 2012) less than 1% (89 instances) were operating below 48% LHV efficiency. (Of those, some were showing 0% efficiency, suggesting a system shutdown or other issue.) Less than 3% (256 instances) operated below 50% LHV efficiency. The data suggests that fuel cells are almost always being replaced before hitting the 48% LHV efficiency threshold.

Appendix B—Breakdown of Federal, State, and Local Subsidies to Bloom Energy

Here’s a breakdown of Bloom Energy’s subsidy receipts to date:

Federal Energy Investment Tax Credit (ITC): This program is often associated with solar and renewable energy. Bloom has received an estimated $360 million from the program, but these subsidies are stepping down starting in 2020. We estimate that this step-down will result in $247 million in foregone subsidies to Bloom over the next 3 years at current annual run-rates.

We estimated the $360 million number by applying the 30% ITC to roughly $1.2 billion in product & installation revenue since 2014. We based our estimate of the foregone subsidies over the 3-year step-down period by using the 2018 annual run rate applied to the modified ITC percentage subsidies from the link above.

California Self-Generation Incentive Program: Bloom received $376 million from this program as of 7/29/2019. In 2016, California modified the program after releasing a report indicating that Bloom Boxes were too expensive and released too much carbon to warrant incentives.

The modified incentive system requires replacing natural gas with biogas. With 91% of Bloom’s servers operating on natural gas, the change rendered the program largely out of reach for the company. It is set to expire January 1, 2021 regardless.