Summary (NASDAQ: OPRA)

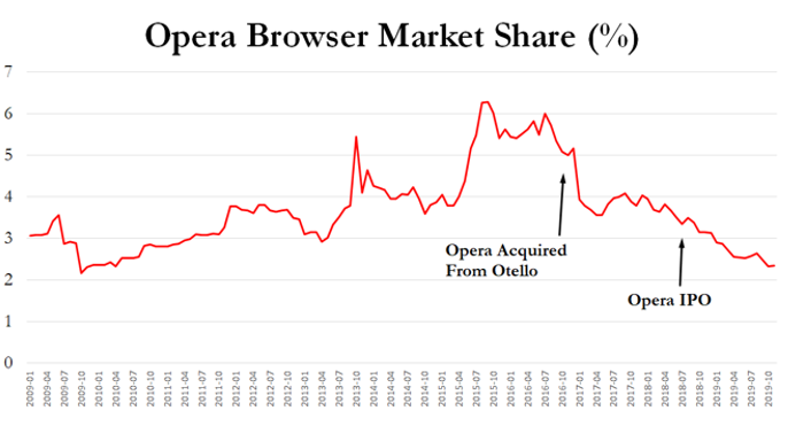

- Opera went public in mid-2018 based largely on prospects for its core browser business. Now, its browser market share is declining rapidly, down ~30% since its IPO.

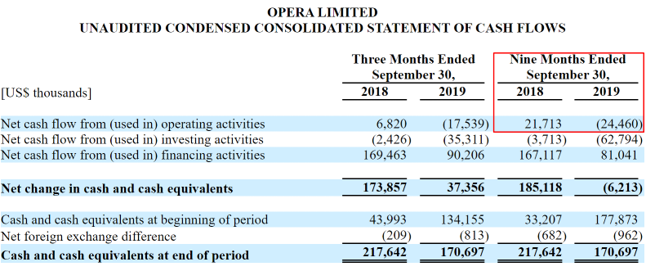

- Browser gross margins have collapsed by 22.6% in just one year. Opera has swung to negative $12 million in LTM operating cash flow, compared to positive cash flow of $32 million for the comparable 2018 period.

- Opera was purchased by a China-based investor group prior to its IPO. The group’s largest investor and current Opera Chairman/CEO was recently involved in a Chinese lending business that listed in the U.S. and saw its shares plunge more than 80% in just 2 years amid allegations of fraud and illegal lending practices.

- Post IPO, Opera has now also made a similar and dramatic pivot into predatory short-term loans in Africa and India, deploying deceptive ‘bait and switch’ tactics to lure in borrowers and charging egregious interest rates ranging from ~365-876%.

- Most of Opera’s lending business is operated through apps offered on Google’s Play Store. In August, Google tightened rules to curtail predatory lending and, as a result, Opera’s apps are now in black and white violation of numerous Google rules.

- Given that the vast majority of Opera’s loans are disbursed through Android apps, we think this entire line of business is at risk of disappearing or being severely curtailed when Google notices.

- Instead of disclosing to investors that its “high-growth” microfinance segment could be imperiled by these new rules, Opera instead immediately raised $82 million in a secondary offering without disclosing Google’s changes to investors.

- Opera’s short-term loan business now accounts for over 42% of the company’s revenue and is responsible for eye-popping top line “growth”. Meanwhile, the segment experienced massive defaults (~50% of lending revenue) and company-wide cash flow has worsened.

- Post IPO, Opera promptly directed ~$40 million of cash into businesses owned by its Chairman, including $30 million into a karaoke app, and $9.5 million into an entity used to acquire a business that Opera had already operated and funded, via a questionable transaction.

- We think Opera collapses on its own worsening financials, with that timeline accelerating significantly if Google bans its lending apps or if its Chairman/CEO continues to draw cash out of the business through questionable related-party deals.

Initial Disclosure: After extensive research, we have taken a short position in shares of Opera. All APR extrapolations/calculations were based on a 365 day year. This report represents our opinion, and we encourage every reader to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report.

Introduction

When a new management team takes over a declining business, it can become a race against the clock to cash out. This is what we think is going on at Opera, a company based around a once-popular web browser that is now seeing its userbase erode.

In the year and a half since its IPO, Opera’s browser has been squeezed by Chrome and Safari, with market share down about 30% globally. Operating metrics have tightened, and the company’s previously healthy positive operating cash flow has swung to negative $12 million in the last twelve months (LTM) and negative $24.5 million year to date.

With its browser business in decline, cash flow deteriorating (and balance sheet cash finding its way into management’s hands…more on this later), Opera has decided to embark on a dramatic business pivot: predatory short-term lending in Africa and Asia.

The pivot is not new for Opera’s Chairman/CEO, who was recently involved with another public lending company that saw its stock decline more than 80% in the two years since its IPO amidst allegations of illegal and predatory lending practices.

Opera has scaled its “Fintech” segment from non-existent to 42% of its revenue in just over a year, providing a fresh narrative and “growth” numbers to distract from declining legacy metrics. But with defaults comprising ~50% of lending revenue, this new endeavor strikes us more as short-term window dressing than a long-term fix.

Furthermore, Opera’s short-term loan business appears to be in open, flagrant violation of the Google Play Store’s policies on short-term and misleading lending apps. Given that the vast majority of Opera’s loans are disbursed through Android apps, we think this entire line of business is at risk of disappearing or being severely curtailed when Google notices and ultimately takes corrective action.

Meanwhile, Opera has exhibited a troubling pattern of raising large amounts of cash (almost $200 million over the past 1.5 years), and then directing portions of it to entities owned or influenced by its Chairman/CEO through a slew of questionable related-party transactions. For example:

- $9.5 million of cash went toward an entity that appears to have been owned 100% by Opera’s Chairman/CEO, despite company disclosures suggesting otherwise. Ostensibly, the reason for the payment was to ‘purchase’ a business that was already funded and operated by Opera. To us, this transaction simply looks like a cash withdrawal.

- $30 million of cash went into a karaoke app business owned by Opera’s Chairman/CEO, days before the arrest of a key business partner.

- $31+ million of cash was doled out for “marketing expenses and prepayments” to an antivirus software company controlled by an Opera director and influenced by Opera’s Chairman/CEO. The antivirus company has no other known marketing clients, but is paid to help Opera with Google and Facebook ads and other marketing services. (Note: Most firms use a marketing agency for help with marketing needs.)

We have a 12-month price target of $2.60 on Opera, representing ~70% downside.

We take the midpoint of the company’s $43 million annual adjusted EBITDA expectations and assign multiples to its business units weighted by contribution. We apply a 7x EBITDA multiple to its browser & news segment (despite the steep profit decline) and a 2x EBITDA multiple to its lending apps, in-line with Chinese peers. We do not assign a multiple to its licensing segment, which the company has stated it expects to “significant decline”. The company has about $134 million in cash (no debt) which we add.

We then apply a 15% discount to account for risks relating to its fintech division, which we believe will be significantly curtailed over the next 12 months (for reasons we explain) and risks relating to management and cash dissipating via questionable related party transactions.

Background

Pre-IPO: A Rosy Looking Story

Opera is a browser and mobile app business that has existed since the early days of the internet.

The browser business emerged in 1995 and maintained a niche share of the market over the years. In November 2016, Opera’s browser and apps division was acquired by a China-based consortium including Kunlun Tech and Qihoo 360. Kunlun Tech is a publicly traded Chinese company focused on online game development and is led by Opera’s chairman and CEO, Yahui Zhou. Qihoo is a popular, but controversial (1,2,3,4), browser company in China led by Opera Director Hongyi Zhou.

When taking Opera public in July 2018, the browser and apps business was growing gross profit at 30-40%. The business had 40% EBITDA margins and it was generating positive cash flow [pg. S-8].

Post-IPO: A Quick Collapse in Opera’s Browser Market Share

Within months of transitioning to new management, Opera’s growth and profitability in the browser and mobile ad business began to decline rapidly. The decline has continued post-IPO. Opera’s global browser market share has dropped from 5%+ pre-acquisition to just over 2% most recently.

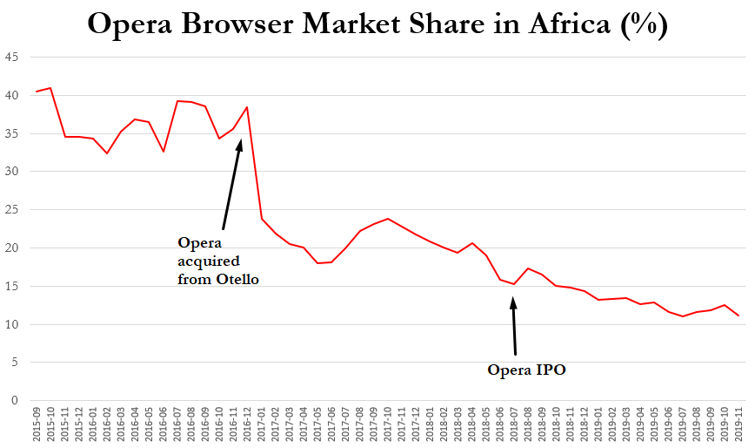

In Opera’s strongest market, Africa, the declines were even more pronounced. Opera’s browser market share in Africa hit highs of ~40% prior to its acquisition by new management and has plunged below 12% as of the most recent period. Opera’s browser share has quickly been squeezed out by Google on one side, and Safari on the other, as Android and Apple have both developed stronger footholds on the continent.

Post-IPO: A Quick Collapse in Opera’s Financial Metrics, Negative Cash Flow and Declining Browser Margins

This deterioration has contributed to “Browser and News” segment gross profit declines of 22.6%, from $76 million to $59 million in the most recent y/y period [Q3 2019 report].

On the cash flow side, the company generated negative $24.5 million in operating cash flow in the nine months ended September 30, compared to positive cash flow of $21.7 million for the comparable 2018 period.

But Alas, A New Business Has Emerged That Has Sent Reported Revenue Soaring: Predatory Short-Term Lending in Africa and Asia

Coinciding with these challenges, Opera launched a mobile app based short-term lending business, now labeled under its “Fintech” segment, that scaled from no revenue in 2018 to 42.5% of Opera’s revenue in Q3 2019.

As we will show, Opera’s apps have entered the African and Asian markets offering short-term loans with sky-high interest rates ranging from ~365%-876% per annum.

As one former employee of an Opera lending app described to us, in many cases “these (loans) are for people (who) could not even afford their basic needs.” Another employee described a desperate Kenyan borrowing market, stating:

“Most Kenyans, they are low income earners. And apparently most of them they don’t have enough even for their families.”

The Predatory Lending Business Has 50% Credit Losses and Limited Profitability, But It Makes Top-Line Growth Appear Great

In all loan businesses, giving away money is easy and growth can be as fast as a company wants – until, of course, the loans need to be paid back. In its latest quarter, Opera reported that its credit losses reached $20 million, an astounding ~50% of its $39.9 million Fintech segment revenue for the quarter.

While mobile app loans can be a lot less profitable (bottom line) than the traditional search & advertising businesses due to high incidences of non-performing loans, Opera had nonetheless given itself the ability to report high revenue growth (top line) and project a more optimistic future.

The short-term lending business was initially launched in Kenya and showed immediate growth from $6.5 million in Q1 2019 [Q1 Results] to $11.6 million in Q2 2019 [Q2 Results] to $39.9 million in Q3 2019 [Q3 Results].

The apps have improved reported net income as well, but largely through non-cash valuation increases. Year to date (YTD) net income was $35.9 million, with $26.2 million (73%) stemming largely from level 3 asset markups among its Fintech apps.

We think Opera’s lending business will fail purely on economics: default rates, competition across dozens of similar apps and user turnover will continue to take its toll on cash flow and profitability despite any top line revenue growth.

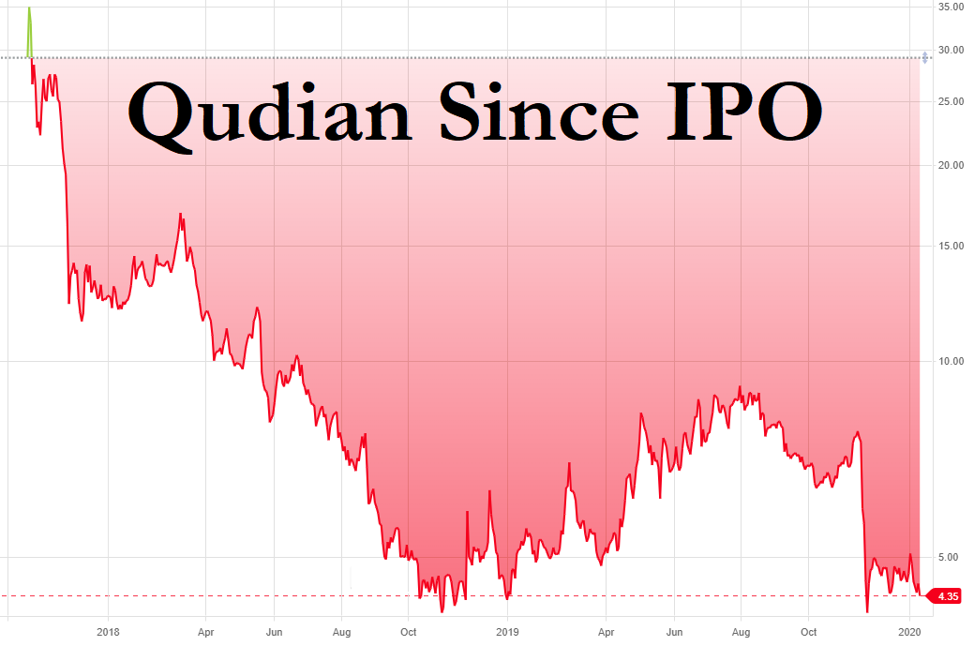

And we think Opera’s Chairman/CEO Yahui Zhou knows this drill well, having recently lived it. Zhou has a close association with another lending business, Qudian (NYSE:QD), which has plummeted more than 80% since its IPO ~2 years ago due to the same types of concerns we are raising about Opera. We dig into the striking parallels between these two companies later in our report.

Beyond basic economic unsustainability, we have found several additional issues that we think could lead to a near term evisceration of the company’s newfound predatory lending business.

Part I: Opera’s Pivot to Sketchy Short-Term Lender Is Already Imperiled

Opera is Flagrantly Disregarding Google’s New Policies on Predatory Short-Term Lending

Opera has 4 apps that collectively offer lending products in Kenya, India, and Nigeria, mostly through Google’s Android operating system. Google/Android has over 84% market share in Kenya, over 94% market share in India, and over 79% market share in Nigeria, making it the overwhelmingly dominant platform that individuals in these markets use for personal loan apps. Opera’s access to the Google Play store is therefore critical to the success of its lending apps.

We have found clear evidence that all 4 of Opera’s lending apps are in black and white violation of Google’s rules on short-term lending and deceptive/misleading content. We will demonstrate this evidence in this report. We have also reached out to Google for comment on our findings.

We believe this is a significant risk to Opera investors. Without the support of Google, we have a hard time imagining this predatory lending business survives. We also have a hard time imagining Google takes no action when they realize the extent of the violations and the havoc these apps have created in the lives of some of the world’s most vulnerable users in Africa and India. The social consequences of these mass-default products appear to be mounting, as we will detail.

Google’s Rules: Apps That Offer Short-Term Personal Loans of 60 Days or Less Are Not Allowed

Opera: All of Our Apps Offer Loans Ranging From 7 Days to 30 Days Despite the Ban (And Despite Pretending to Be in Compliance)

Historically, Google had relatively vague policies against harmful financial products, stating:

“We don’t allow apps that expose users to deceptive or harmful financial products and services.”

In August 2019, Google updated its policies in response to a proliferation of predatory lending taking place on its app ecosystem. The updated policies were much more specific, prohibiting “short-term personal loans” (defined as loans less than 60 days). [Source 1, Source 2, Source 3]

The updated policy reads:

“We do not allow apps that promote personal loans which require repayment in full in 60 days or less from the date the loan is issued (we refer to these as “short-term personal loans”). This policy applies to apps which offer loans directly, lead generators, and those who connect consumers with third-party lenders.”

Opera’s mobile loan business operates through four Android apps: (1) OKash and (2) OPesa in Kenya, (3) CashBean in India, and (4) OPay in Nigeria.

We had consultants test Opera’s lending apps in December 2019 and January 2020 and found that all four of its apps were in black and white violation of Google’s rule, as we will show. In fact, none of the loan products offered across Opera’s apps appear to be in compliance with this policy, despite these rules going into effect over 4 months ago.

About 2 months after Google instituted its personal loan policy change, Opera’s Chief Financial Officer, Frode Jacobsen, was asked about the company’s loan profile. Jacobsen stated on the company’s November 2019 conference call that its loan duration was still about 2 weeks:

“So our loans in India tends to be a bit bigger, in the $50; whereas in Kenya, it’s in the $30. So while duration of loans, it’s about the same with an average of about 2 weeks, as you mentioned.“

This is corroborated by Opera’s most recent prospectus, dated September 2019 (after the rule change). Disclosures show that Opera’s entire microlending business provides loans between 7 to 30 days, which all fall outside of Google’s policies [pg. F-11]:

“The Group currently provides loans to consumers with a duration of between 7 to 30 days.”

The same prospectus fails to mention Google’s rule change.

All 4 Of Opera’s Apps Pretend to Be in Compliance with Google’s Policies, But in Reality, They All Offer Prohibited Products

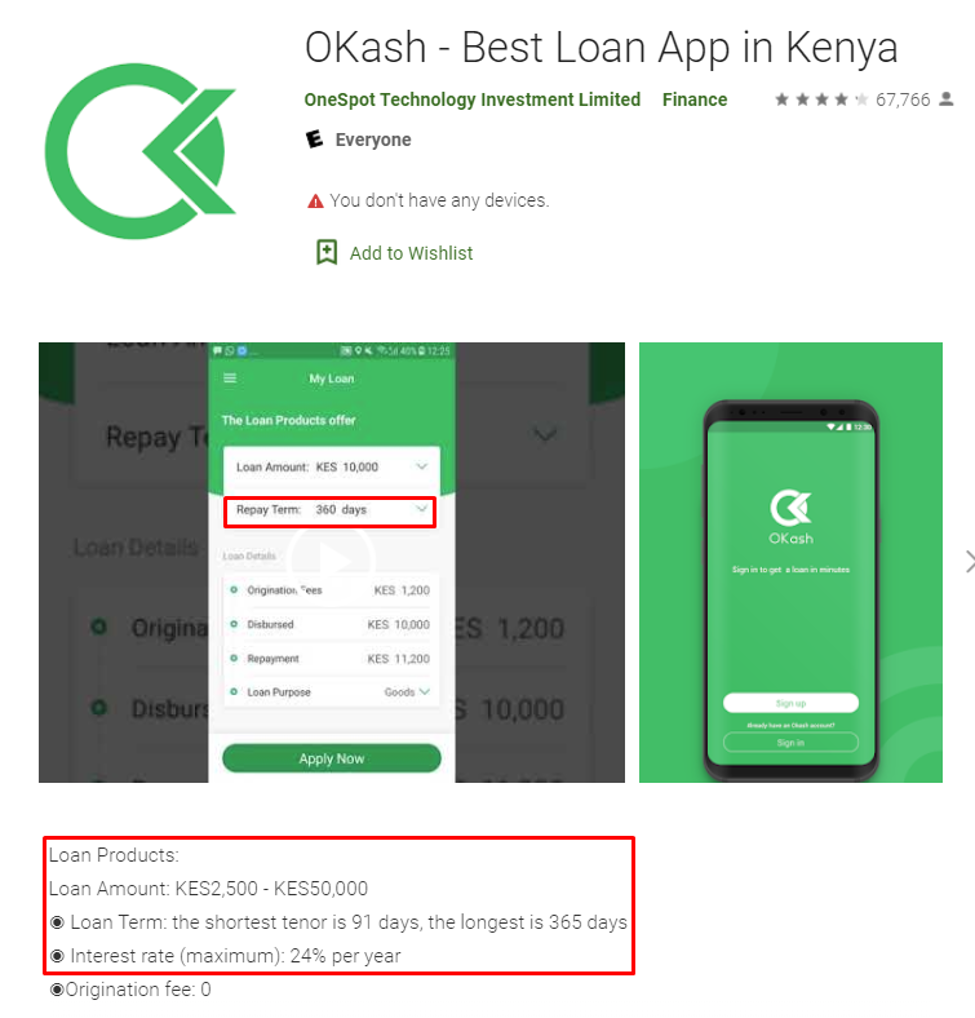

When we first discovered that Opera’s lending apps were in flagrant violation of Google’s rules, we wondered how they had not been banned or been required to bring their terms into compliance. The reason, we think, is because each app claims to be in compliance with the new policies in their respective Google app descriptions, but then offers prohibited loans once users have downloaded and signed up for the apps.

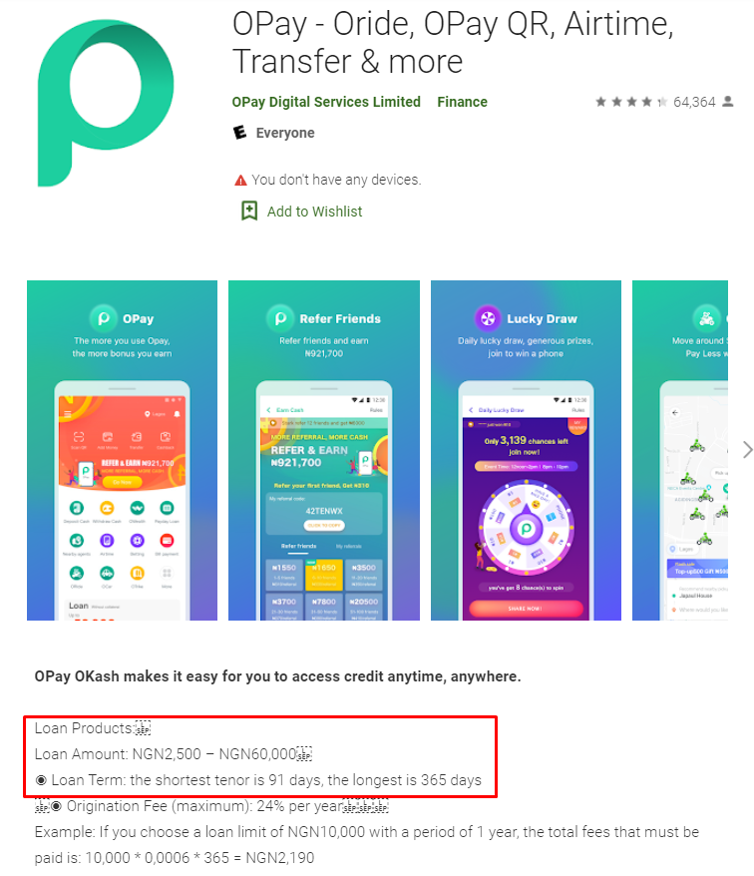

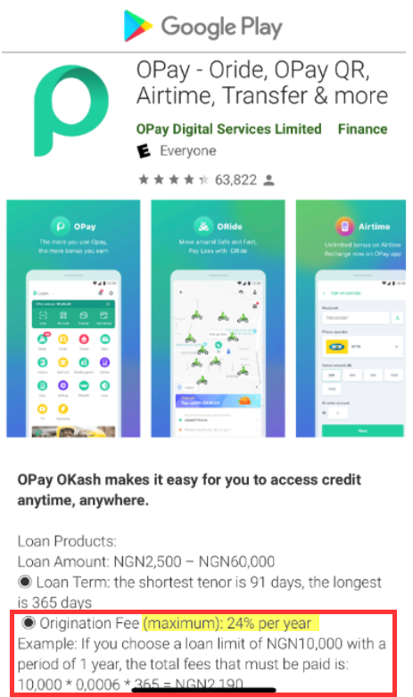

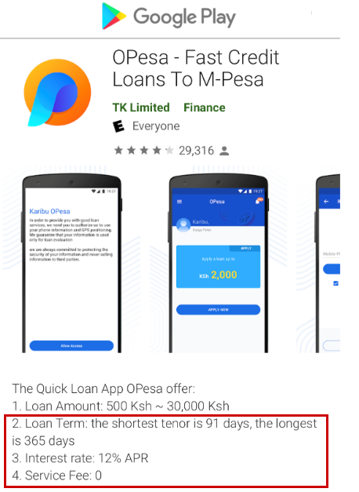

For example, here is the Google Play app description for OKash, which clearly states that its loans range from 91 days to 365 days, which would place it in compliance with Google’s policies. Even the example image shows a loan offered with a term of 360 days:

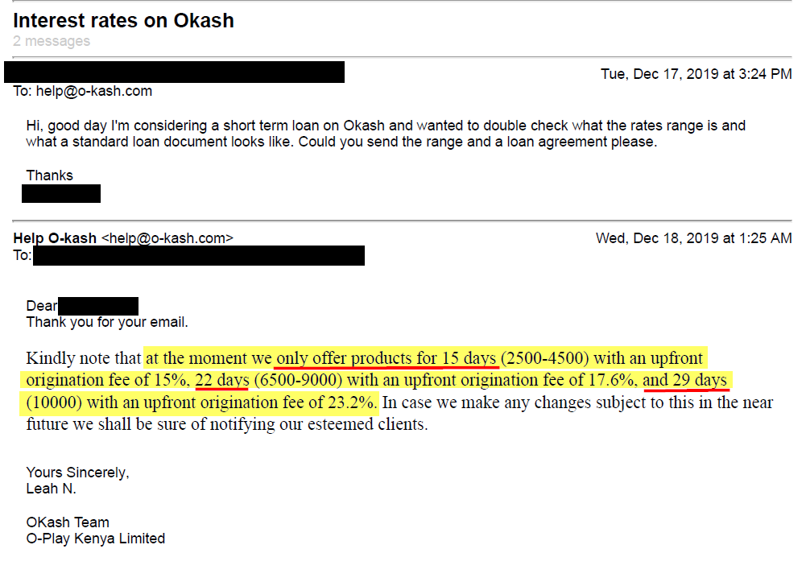

But these products don’t appear to exist at all. An email to the company’s OKash app division confirms that loans range from 15 days to 29 days in duration:

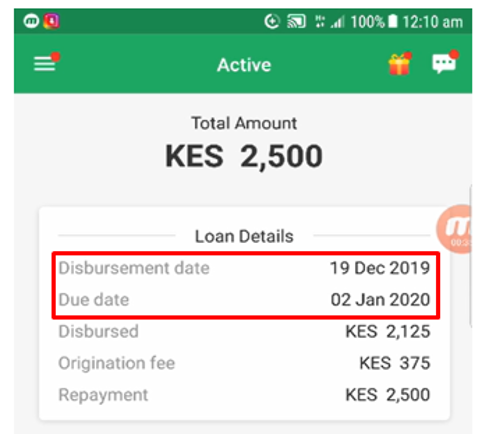

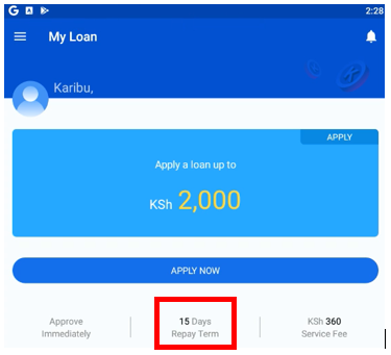

We further confirmed this by having a local consultant apply for a loan through the OKash app. They were given a 2-week loan:

All of Opera’s Apps Exhibit the Same Pattern: A Misleading Description that Looks to be in Compliance, But Products Openly Violate Google’s Terms

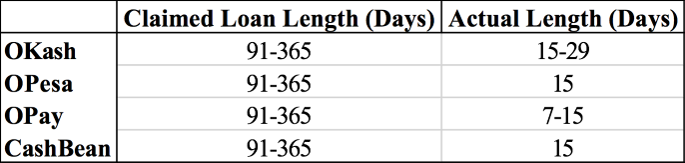

In addition to OKash, we reviewed the claimed loan length on the Google Play Store versus actual loan length for Opera’s other lending apps. The pattern is clear. Here is the summary of our findings for all 4 apps, with more individual details following:

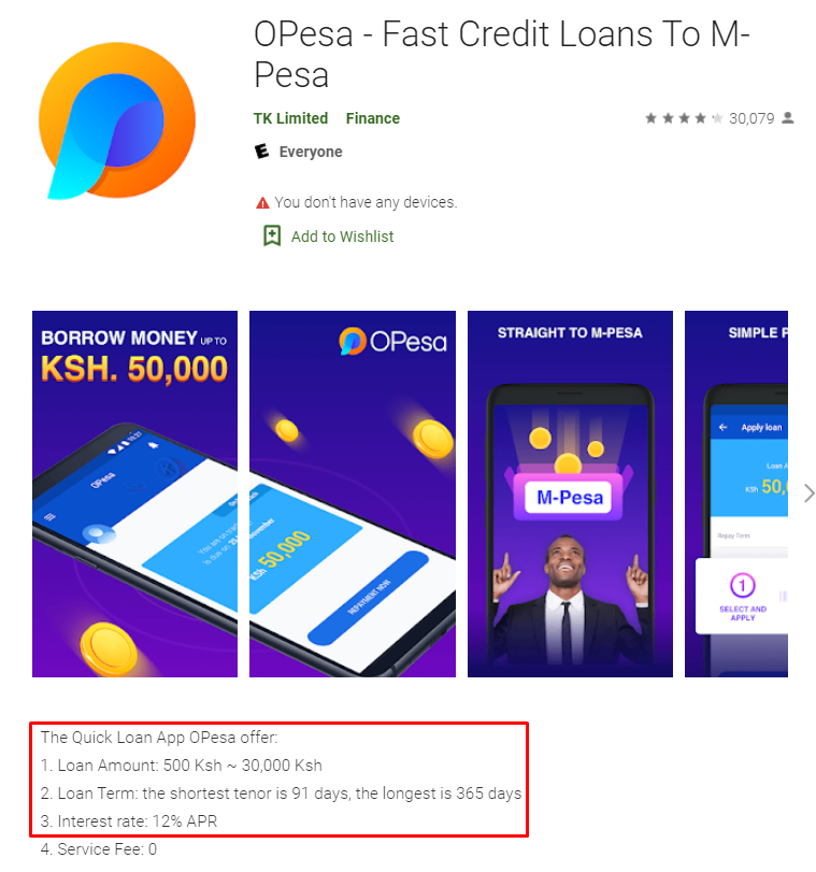

OPesa’s app description similarly presents its loan terms as being between 91 days to 365 days, despite no evidence that it ultimately provides any loans of those lengths.

There wasn’t even much sleuth work required for OPesa. After all, the app’s own FAQ page shows that it offers a loan term of 14 days with an origination fee of 16.8%, which equates to an APR of ~438%.

To confirm this, we had our consultant download the app in mid-December. They were offered a repayment term of 15 days.

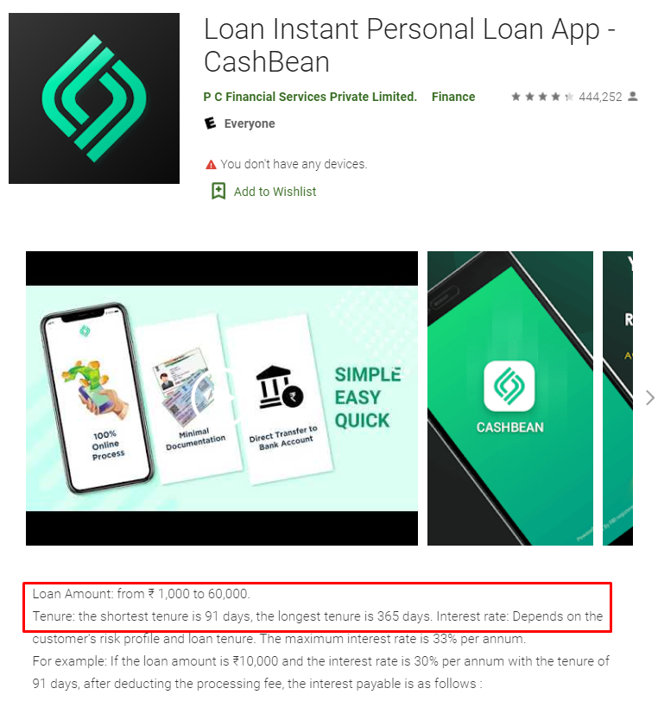

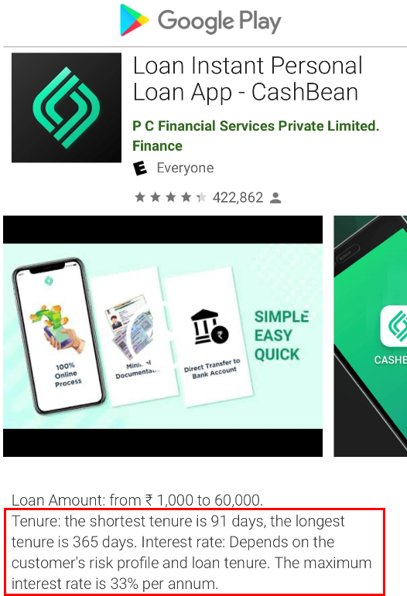

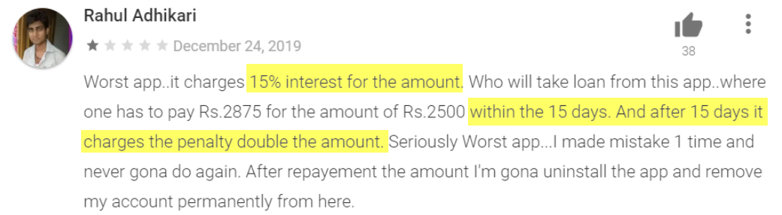

For CashBean (India), the app description once again makes the same 91 day to 365 day loan term claim.

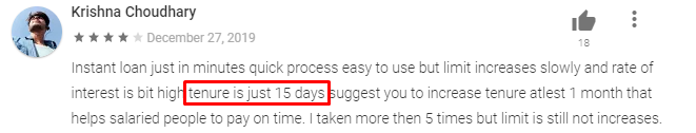

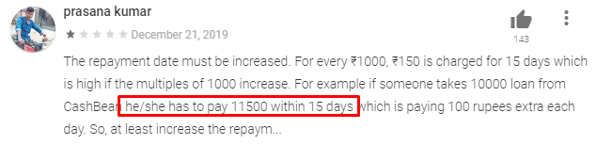

Yet recent online reviews for the app consistently show the loan term to be 15 days:

We emailed the company to see if they offer loans for any term other than 15 days and have not heard back as of this writing.

OPay’s app description also makes the exact same 91 day to 365 day loan term claim.

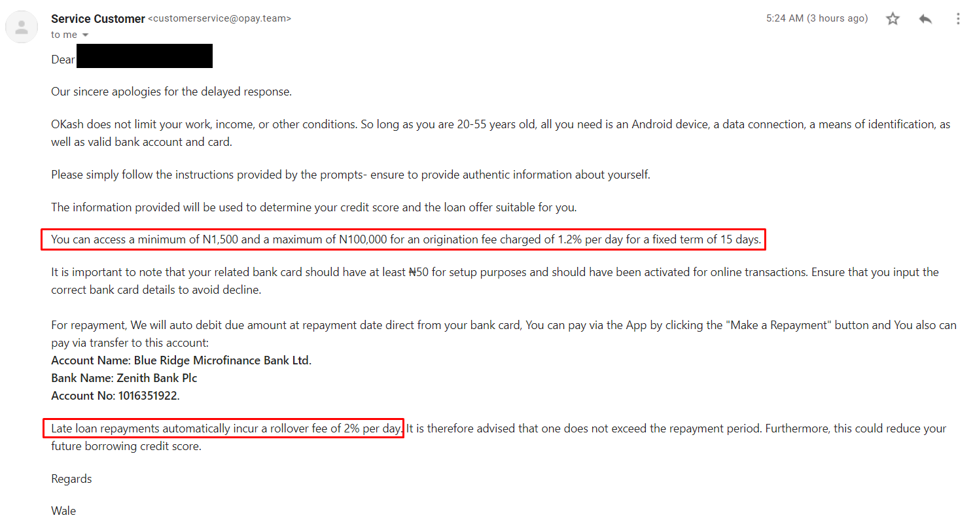

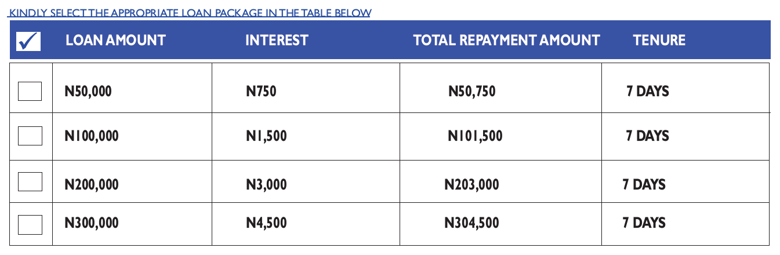

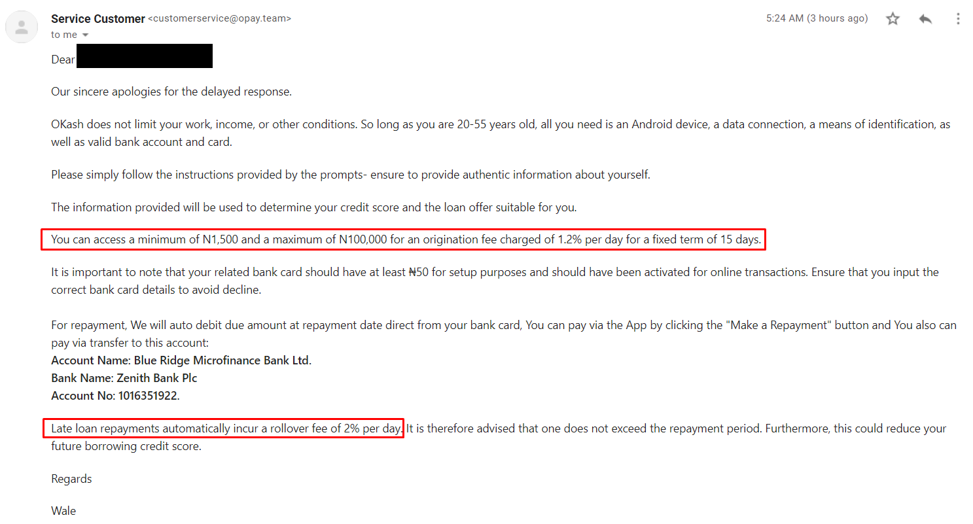

We also inquired about the company’s loan terms via an email to customerservice@opay.com. They replied that the loan’s rate and term would be “an origination fee charged of 1.2% per day for a fixed term of 15 days”:

In a separate email chain, OPay ultimately provided us a loan application that offered only loans with a 7-day tenure:

And so, despite Opera having 4 different apps across 3 countries, it appears that each violates Google’s Play Store rules and skirts compliance using the exact same technique. We have a hard time believing that to be accidental.

Rather than Updating the Market on The Material Policy Change That Could Eviscerate Its Lending Business, Opera Said Nothing and Immediately Raised $82 Million in a Secondary Offering

Google’s short-term lending policies were updated in August 2019 and would have had a materially negative impact on Opera’s lending model, had the company chose to abide by them.

Amortizing high-interest rate loans over a longer period of time to “high-risk” borrowers would change the borrower profile, impact default rates and create a headwind for the segment.

We believe most law-abiding companies would have promptly disclosed this rule change and reassured the market on their plans for adapting to it.

Instead, Opera appears to have disregarded the new policies entirely, disclosed nothing about the change to the market, even when it launched a secondary offering in mid-September that raised net proceeds of about $82 million.

Google’s Rules: Your App Description Can’t Be Misleading and Must Include Accurate Loan Length, APRs and Representative Examples

The above documentation clearly shows that Opera is violating the Google Play Store rules on short-term loans. A further review shows the company to be in violation of additional rules.

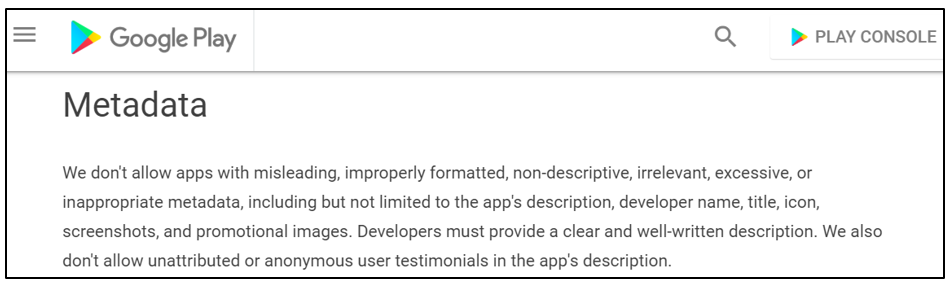

For example, Google’s policies require that the metadata of apps be accurate:

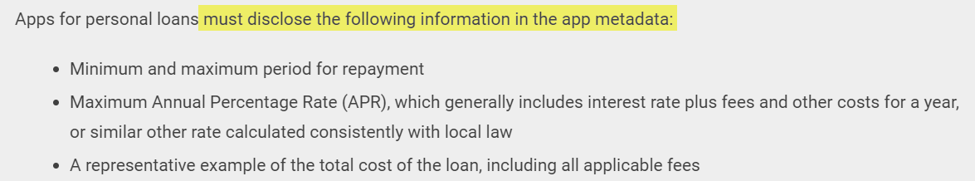

Furthermore, Google’s personal loan policies require certain metadata to be included in app descriptions. This includes:

- The minimum and maximum period for repayment (already shown above to be false in Opera’s app descriptions);

- Annual percentage rate of the loan, including fees; and

- A representative sample of a loan and its total cost

Opera’s apps flagrantly violate each of these terms in its app descriptions.

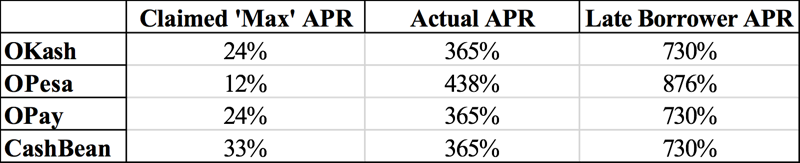

Opera’s App Descriptions: Interest Rates Are 12%-33% Max Per Year (APR)

Opera’s Actual APRs: 365%-438%.

Opera’s APRs if a Borrower is Late by One Day: 730%-876%

Kenya, Nigeria, and India are home to some of the world’s most disadvantaged individuals. Borrowers turning to short-term loans may lack access to traditional bank loans. These people are more likely to be vulnerable and fall for misleading offers.

We think Opera is taking advantage of these people by claiming to offer low rates and longer-term loans then gouging borrowers with sky high rates and shorter terms.

We reviewed all of Opera’s lending apps and found that each claimed to offer low rates in its app descriptions. Based on our research, however, none of its apps charge the stated interest rates and all ultimately charge obscenely high rates:

A Pattern of Luring in Unsuspecting Borrowers with a Classic Bait and Switch

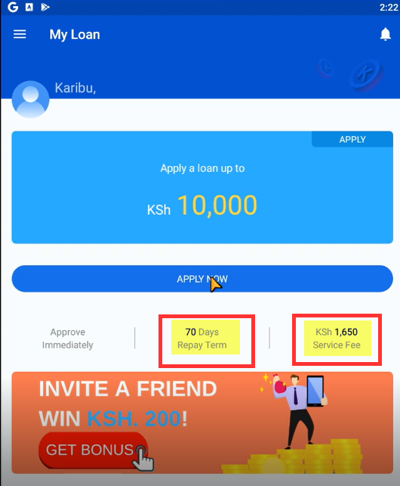

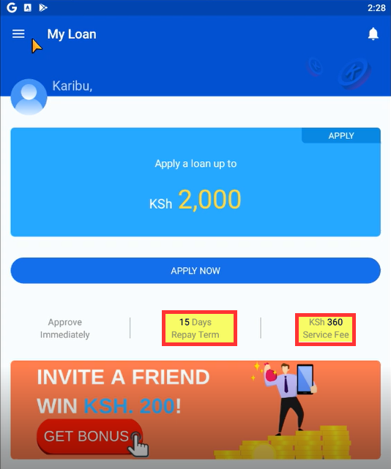

Additionally, we saw what appeared to be a 3-step pattern of ‘bait and switch’ on loan terms in each app:

- The app description would lure in users with low rates and long loan length terms.

- Once downloaded, the app would then suggest users apply for a loan, showing a slightly longer loan length and terms that suggest a higher interest rate.

- Once the user inputs their personal information and applies, the apps then either deny the borrower or grant a short-term loan with sky-high rates.

A former employee of OKash described to us how unemployed individuals were often totally unaware of the high interest rates they were paying, until it was too late:

“Most people are not educated. You see when you are downloading an app and opening an account there are those terms and conditions. Most people never read the terms and conditions. So when you are telling a person you are expected to pay a 1% fee (per day) after you failed to pay the loan back…by the time that person finds out it’s like 20 days.“

“…Now the rates had gone high and these are for (unemployed) people who could not even afford their basic needs.”

Breaking Down the Bait and Switch Model for Opera’s 4 Lending Apps: Worsening Terms Every Step of the Way

We took a granular look at what Opera’s apps claim they offer in the way of interest rates, versus what is happening in practice.

- OPay (Nigeria)

OPay’s app description says loans are offered with a ‘maximum’ interest rate of 24% a year in the form of an origination fee:

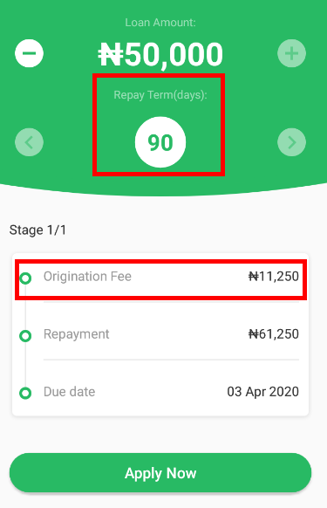

When users get into the app, however, they see options for 60 to 90-day loans with origination fees that correspond to a 91% APR.

But when users actually apply, a process that requires providing personal information and paying a fee, they appear to instead be granted 15-day loans for significantly lower amounts. See an example from one user below:

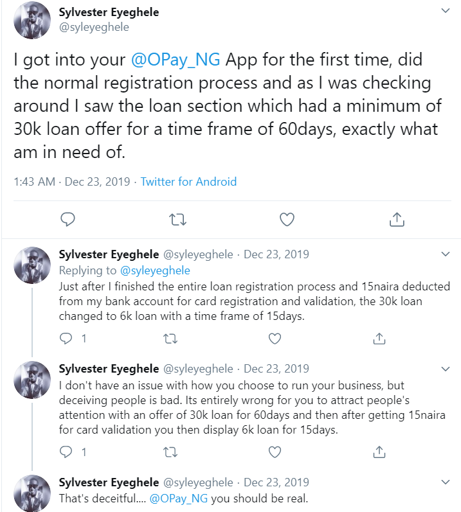

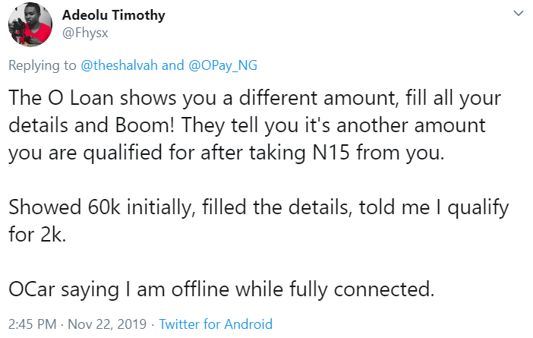

We saw multiple recent users on social media complaining of these same ‘bait and switch’ tactics [1,2,3]:

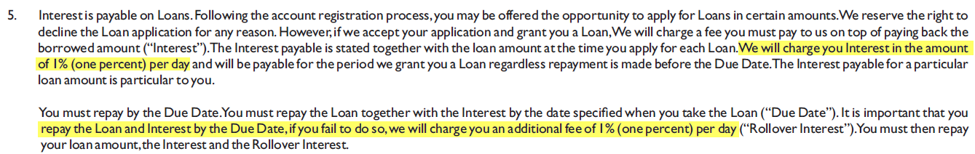

As to the actual interest rates, we received loan documents from OPay as part of our research. The fine print at the bottom of the contract shows that the interest rate is 1% a day, plus another 1% per day if a user is late. In other words; 365% per year, or 730% for late borrowers:

An email to OPay customer service detailed an even higher 1.2% per day fee for 15 days and a 2% fee per day for late loan repayments.

Given that these rates aren’t presented until the end of the borrowing process, users likely don’t learn that they have a 2-week loan at absolutely crippling interest rates at the very last minute.

2. OPesa (Kenya)

OPesa’s lending app description shows a reasonable 12% APR with no service fee:

When our consultant tested OPesa in late December, the screen prompting them to apply for a loan showed a less attractive loan term of 70 days with service fees that suggested an APR of about 86%:

Once they put in all of their personal information, the loan terms were again worsened to a 15-day loan with an APR of 438%!

In the fine print of the OPesa terms of service, we see that late loans are charged at a rate of 2.4% per day, an APR of 876%.

The only other place we see the real OPesa terms are the app’s FAQ page, which contradicts the terms presented in the app description and the loan application process.

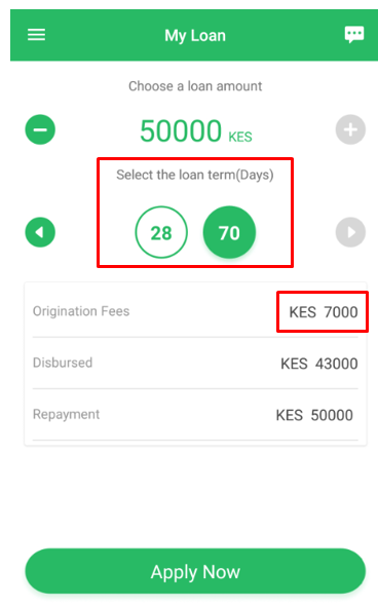

3. OKash (Kenya)

And here is the app description for Opera’s OKash, showing that the maximum interest rate is 24% per year with no origination fees.

When it came time to apply, the app first suggested that our consultant could get a loan for 28-70 days, at an implied APR of 84% through origination fees:

But then the actual loan term for our consultant ended up being 2 weeks, at an APR of 365%.

These rates were also corroborated by our email exchange with OKash support shown earlier, which confirmed that the actual interest rate is approximately 1% per day (365% APR), charged in the form of an up-front origination fee.

According to the app’s Terms of Service, late users are charged 2% per day if late, an APR of 730%!

4. CashBean (India)

Lastly, Opera’s CashBean description suggests a “maximum” APR of 33%.

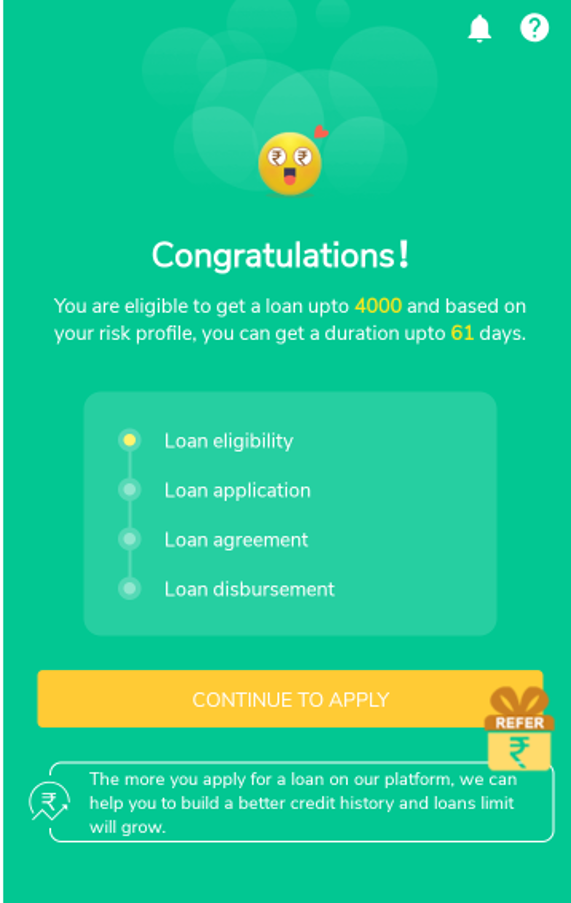

Once our consultant began the loan application process by inputting their basic information, the app once again lured them in with a suggestion that they could get a loan “duration up to 61 days”:

Our consultant was unable to procure a loan, but we found numerous user reviews that claimed 15 day loan terms at 15%, which doubles if late (365%-730% APRs). Here are two recent examples:

Google’s Rules: “We Don’t Allow Apps That Expose Users to Deceptive or Harmful Financial Products or Services.”

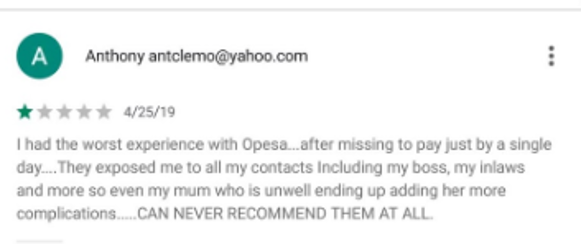

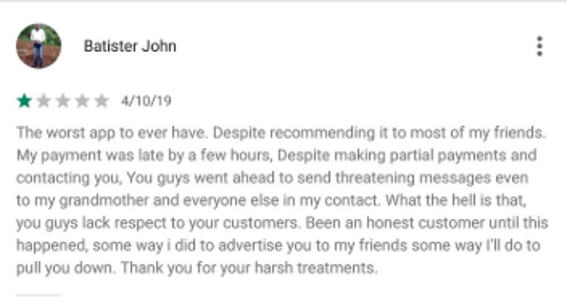

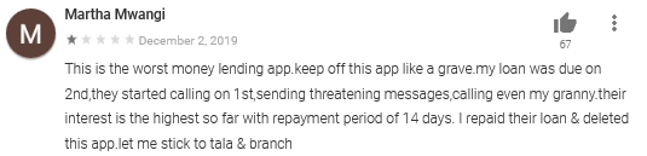

Opera: When Borrowers Were Late by One Day, We Accessed the Borrower’s Phone Contacts and Harassed Their Friends, Family, Employers, and Co-Workers with Texts and Calls Until the Money Was Repaid

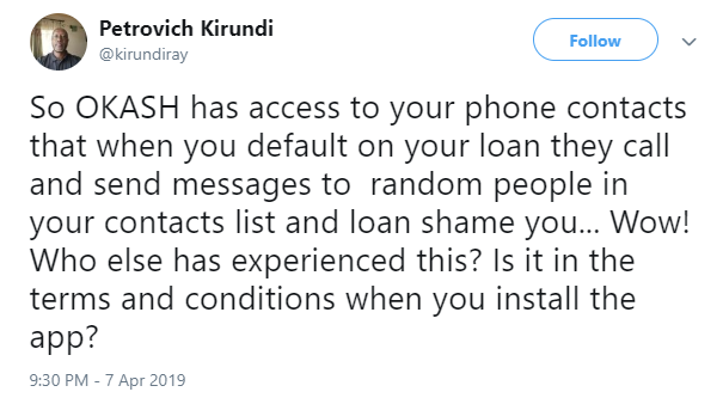

We also learned of a ruthless OKash and OPesa collection policy that was only recently changed as of June 2019, according to a former employee.

If a user was late to repay, the app had previously indiscriminately texted or called contacts in the user’s phone as part of loan collection efforts. This process began immediately after a loan repayment was delayed, according to user reviews.

Numerous users reported that friends, family, employers, and other contacts were harassed and threatened through Opera’s apps when a borrower was late. A Kenyan news article provided one example of the threatening messages used to elicit payment:

“Hello, kindly inform XX to pay the OKash loan of Sh2560 TODAY before we proceed and take legal action to retrieve the debt,’ says the text message the service provider sends to people in one’s contact list.”

This type of public shaming and pressure obviously created devastating social consequences for the borrower. See several examples below from user reviews:

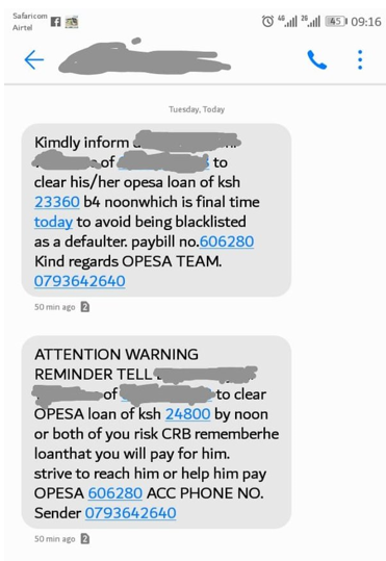

In another example, the apps threatened to place friends or family of a borrower on a national credit blacklist if they didn’t convince the actual borrower to pay:

Additionally, complaints about violation of privacy were found on social media, like Twitter:

We reached out to two Kenyan credit agencies (CRB’s) to ask whether it is actually possible to blacklist a person for simply being a contact in a person’s phone who owes money and have not heard back.

A former OKash employee told us that this practice has been discontinued as of June 2019 “because it was said it was illegal.”

Dire Consequences for Borrowers: Defaulters Are Disproportionately Young People, Often University Students, Who Are Frozen Out of the Job Market and the Banking System

These mass-default lending products can have crippling societal consequences.

For example, several OKash employees described to us a treacherous cycle of fees, which in Kenya can result in the borrower loaded with debt and unable to get a job. Most government and corporate employers require a certificate from the Kenyan credit agencies, known as Credit Reference Bureaus (CRBs), showing good credit. In the absence of such a certificate, many Kenyans are rendered unemployable.

One former OKash employee told us:

“Before you take a loan, they usually ask for your ID number. And for us, using your ID number – there’s usually something called CRB, Credit Reference Bureau…after 30 days they usually forward names of people who haven’t paid to the CRB – the Credit Bureau is where now the Kenyan government can come to ensure that most people pay their loans.“

She continued:

“You cannot get a job if you have a negative CRB – credit score or something. So that’s how businesses ensure that you pay back.“

When we asked another OKash employee about the risks facing the business he said:

“University students. Most of them they are getting into loans. And most of them they don’t have even stable income. That’s a very risky part for the business because you end up having a big number of defaulters of which in the end its very young people who are not yet employed at any point.“

He later described the consequence of these defaults:

“When you are applying for a job in Kenya you need CRB certificate. So that’s also a very major concern…the main problem again, again the issue I was telling you about, the young people, the age group that is around from 18 to around 28…Those are the most guys who are in CRB right now.“

We were also told of how common it is for university students to download multiple lending apps and borrow from each of them to pay off loans from the other, effectively running thousands of mini Ponzi schemes in order to (temporarily) avoid default while they struggle to pay exorbitant interest rates and afford basics.

We’ve Seen This Story Before: Opera Chairman/CEO’s Deep Involvement with Qudian, a Short-Term Lending Flop That Has Plunged More Than 80% In the Two Years Since Its IPO

Opera’s sudden pivot to “micro finance” is not Chairman/CEO Zhou’s first foray into short-term lending or listed companies on US exchanges. Zhou was a director of Chinese lending business Qudian (NYSE:QD) from February 2016 to February 2017, before it went public [Pg. 212]. Kunlun, a China-based company that Zhou controls, was one of the largest investors in the company and owned 19.7% of it when it went public [F-1 Pg. 8].

Qudian raised $900 million in its IPO in late 2017, the biggest U.S. listing ever by a Chinese Fintech firm. The company IPO’d at $24 and has already cratered to about $4.35 as of this writing, a more than 80% decline in a little over two years.

According to a detailed class action lawsuit, Qudian was alleged to have engaged in flagrantly illegal and deceptive lending practices. The parallels to Opera’s current business are striking. The second amended class action complaint against Qudian alleged, among other things:

1. The company falsely stated that it exited making loans to college students in response to a ban by the Chinese government:

“Qudian nevertheless continued to actively operate and promote its business of lending to college students up to the IPO and continued these illegal practices even after the IPO.“

2. The company “employed illegal and unethical means in violation of Chinese laws and regulations, such as threatening students and calling their teachers, parents, or spouses to exert pressure on the borrowers. A former company employee reported that the methods used were so humiliating to young vulnerable students that at least one committed suicide.”

3. The company lent at exorbitant and illegal rates:

“The Company had charged or attempted to charge overdue borrowers a daily interest rate as high as 5% as “penalties” for overdue loans, which, on an annualized basis is 1,825%, i.e., 76 times higher than allowed under the Chinese law.“

The allegations have not been proven and the lawsuit is still pending before the court.

Beyond the obvious similarities to Opera’s new predatory lending business, Qudian’s financial metrics also show parallels. The company had periods of massive revenue growth (at one point almost 500% y/y) yet its delinquency metrics, competition, and partner/regulatory hurdles ultimately have begun to catch up with it.

Once again, it is easy to give money away—the hard part is making sure it comes back (particularly when lending to the world’s most disadvantaged at sky-high rates.)

Conclusion: Investors Should Be Wary of Opera’s ‘Pivot’ to Sketchy Short-Term Lender and Its Flagrant Violation of Google Play Rules

We think Opera’s new ‘high growth’ lending business should raise alarm bells for investors. Opera’s willingness to engage in deceptive, predatory lending to some of the world’s most vulnerable people should say something about the approach embraced by management.

As we were told by a former OKash employee in Kenya, the “issue is repayment”:

“Now the issue is repayment. All these citizens are usually able – they can borrow, but most of them don’t have the ability to pay back. Most people who are borrowing from the app – most people are not employed. So when you’re dealing for example – when I was there – when I used to call people during time for repayment, most of them would tell you that they’re not working, so it’s a 50/50 kind of market.“

If Google becomes active about enforcing policies against deceptive and harmful short-term loan apps, we think Opera’s apps are prime examples. We have reached out to Google for comment on these apps and whether they violate its terms and will update this report should we hear back.

Part II: Financial and M&A Mysteries That Don’t Add Up

Opera’s Opaque Related-Party M&A Transactions

Management’s pivot to misleading and deceptive lender to the world’s most disadvantaged raises the question of what other behavior the company condones.

Why Did Opera Pay $9.5 Million for its OKash Lending Business by Purchasing an Entity Owned by Opera’s Chairman/CEO, When Corporate Disclosures Stated Otherwise?

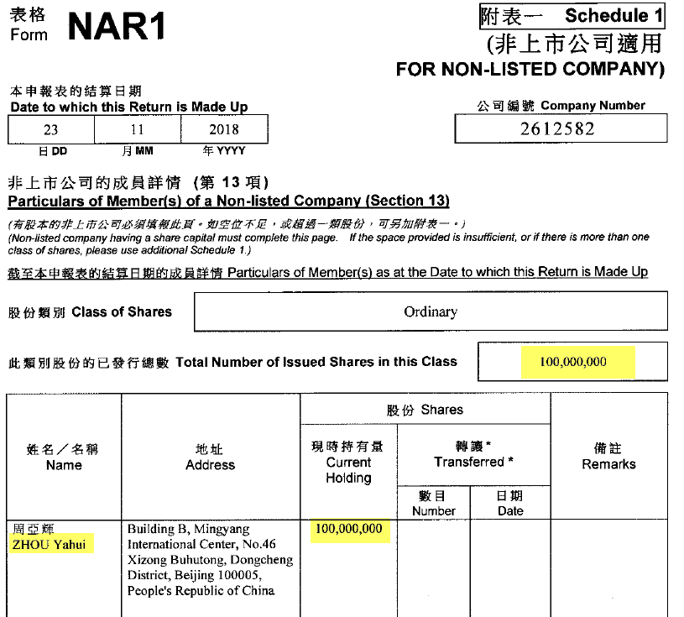

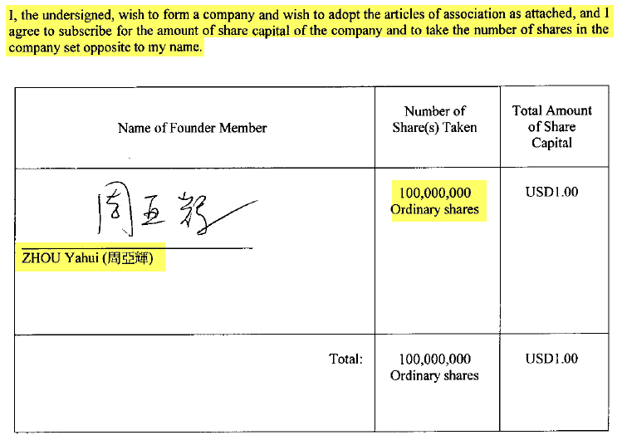

Regarding Opera’s “OKash” Kenyan lending app, we see that the company paid $9.5 million for an entity that Hong Kong records show was 100% owned by the Chairman/CEO, despite company disclosures stating otherwise.

In December 2018, Opera paid $9.5 million to acquire a Hong Kong entity called Tenspot Pesa Limited, which actually owned OKash. [Pg. 92]

Opera Claims it Bought the Entity for $9.5 Million From OPay, a Related Company That Opera has a ~20% Stake In…

Opera stated that it had acquired Tenspot from OPay, a separate company that Opera has a 19.9% stake in. Per the company’s annual results:

“In late December, Opera acquired OKash from Opay for a consideration of $9.5 million.”

This disclosure made sense given Opera’s other public statements on OKash. When Opera initially announced the launch of OKash in March 2018 (about 9 months before Opera acquired it) it stated that it was launched by “OPay, the FinTech company part of the Opera Group.”

…But Hong Kong Corporate Records Contradict This, Showing that Opera’s Chairman/CEO Owned 100% of the Entity the Entire Time

We pulled the Hong Kong corporate records for Tenspot. The annual report filing from just 3 weeks prior to Opera’s acquisition states that OPay did not own the entity. Rather, Opera’s Chairman/CEO Yahui Zhou owned 100% of the entity:

In fact, every Hong Kong corporate document we found showed that the entity was owned 100% by Chairman/CEO Yahui Zhou – from inception until the acquisition by Opera. Here are the articles of association for Tenspot, around the time of its creation in November 2017, showing the same:

How could Tenspot be simultaneously wholly owned by 2 separate parties at the same time?

We reached out to Opera’s investor relations to confirm whether it bought OKash from OPay (as company disclosures stated), or from Chairman/CEO Zhou directly, as Hong Kong entity records state. The investor relations rep wrote that he was “not sure on the specifics of how the entity was set up” but nonetheless re-affirmed “Okash was purchased from OPay (so OPay received the cash not Yahui Zhou).”

Opera Has Funded and Operated OKash Seemingly from the Beginning. So Why Did It Pay $9.5 Million to Own It?

Opera’s investor relations contact also wrote in relation to the OKash transaction that “The business was basically a license when Opera took over”.

This makes sense. Hong Kong corporate records show that Tenspot was created in late 2017, just months before the OKash app was launched, suggesting that the entity was created for the purpose of owning OKash or perhaps a license for OKash to operate.

But as part of the disclosures around the transaction we see that Opera had actually lent at least $2 million dollars to Tenspot, thus it appears to have been funded by Opera since the beginning. [Pg. F-55]

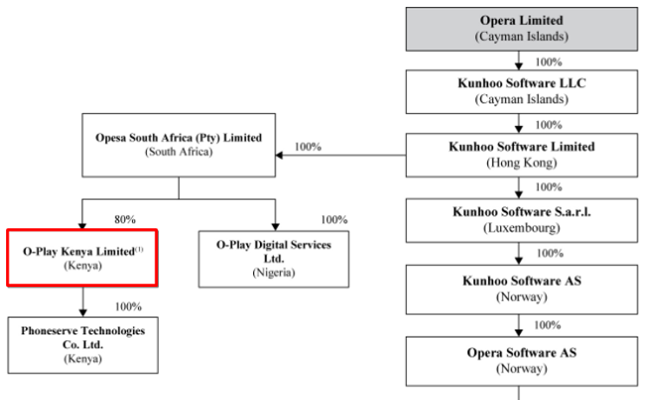

Opera also looks to have operated OKash since the beginning. An Opera filing dated 5 months prior to the transaction [F1 Pg. 51] shows that the company owned 80% of the local operating entity for OKash, O-Play Kenya Limited [pg. 52]:

In other words, Opera funded an entity that it then later purchased for $9.5 million, in order to own a business that it already operated. This strikes us as peculiar.

If the Hong Kong corporate records are correct, and our suspicion is that they are, the “acquisition”, once unpacked, appears to simply be a cash withdrawal by Chairman/CEO Zhou, from the public company and its shareholders.

StarMaker: Why Did a Browser Company Invest $30 Million of Cash into a Private Karaoke App Owned by Its Own Chairman/CEO? (With an ‘Option’ To Invest Another ~$49 Million Soon)

On November 5th, 2018, Opera announced it had invested $30 million in cash into Chairman/CEO Yahui Zhou’s private karaoke app, StarMaker. The investment gave Opera a 19.35% stake in Zhou’s company, valuing the app business at about $155 million.

Zhou had acquired StarMaker in late 2016 for an undisclosed sum. StarMaker’s financials have not been disclosed, but Opera’s most recent 20-F states that it was generating losses [Pg. F-56]. We asked Opera’s investor relations about StarMaker’s financials and they replied that StarMaker was growing revenue and is now profitable.

The app looks to be fairly popular, boasting over 50 million users largely in India, Indonesia, and the Middle East. Nonetheless, investors may wonder, what on earth does a karaoke app have to do with the strategic long-term success of Opera’s browser business (or even with its predatory lending business?)

Opera’s investor relations told us there is “No integration today with Opera and right now viewed as an investment (versus strategic).”

Keep in mind that Opera’s July 2018 IPO raised $107 million in net proceeds [Pg. 1], so the investment into Zhou’s StarMaker app and the investment into the OKash entity represented about 37% of its newly raised cash, out the door, within just about 5 months.

The StarMaker deal also included “an option to increase its ownership to 51% in the second half of the year 2020”, which we estimate would translate into another $49 million cash investment, assuming the valuation remains constant.

We hope the company discloses StarMaker’s financials to investors before Zhou makes an executive decision on that investment.

StarMaker Appears to Have Backed a Crypto Startup Meant to Tokenize Its Revenue Model. Four Days After Opera’s $30 Million Investment, the Crypto CEO was Arrested for Allegedly Looting Funds, Among Other Misdeeds

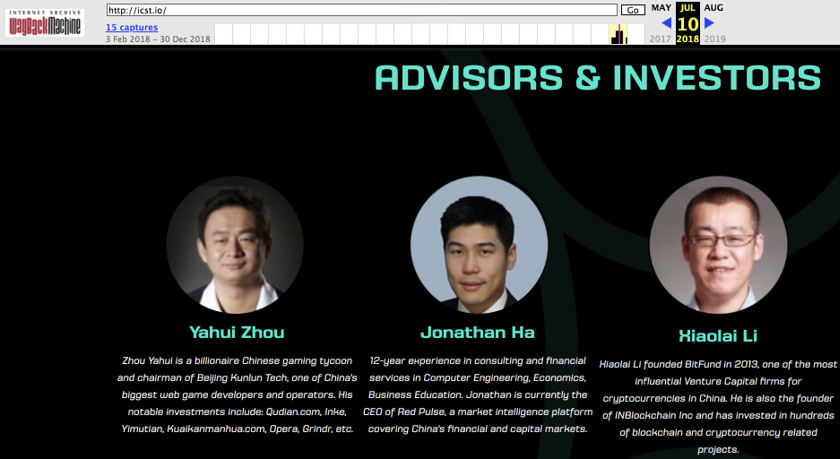

StarMaker ran into some immediate controversy following the Opera investment. In 2018, prior to Opera’s investment, StarMaker appears to have partnered with a crypto ICO called ICST. The ICST token (short for Individual Content and Skill Token) was intended to give content creators a better ability to monetize their intellectual property via the blockchain.

StarMaker was the first partner for the ICO, and StarMaker owner (and Opera Chairman/CEO) Yahui Zhou was the ICO’s key investor/advisor.

The plan was for ICST to transform StarMaker’s revenue model into a tokenized business, and then later branch out into other apps. Yahui was quoted as having a grand vision for the project:

“I see an opportunity to make a great investment, disrupt an entire industry and help creators earn what they deserve“

ICST’s whitepaper detailed the partnership with StarMaker and described how its revenue model would be reliant on the new token.

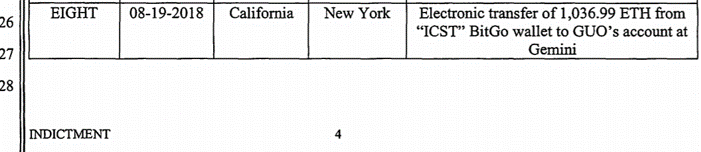

The backing of Zhou and StarMaker helped the ICO raise an estimated $2.5 million USD by June 2018. Opera made its $30 million investment into StarMaker several months later, on November 5th. Four days after Opera’s investment, the CEO of ICST was arrested, with the corresponding DoJ indictment alleging he had stolen ICST funds, among other misdeeds.

See count 8 from the indictment alleging illicit transfers of ICST funds in August, months prior to Opera’s investment:

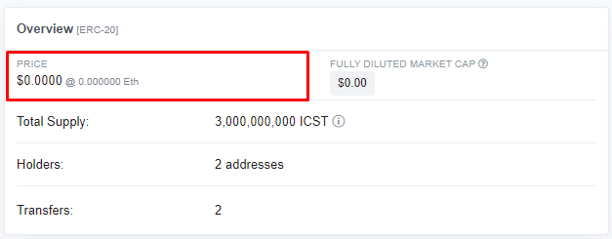

At the time Opera announced its investment, there was no disclosure of any missing ICO funds or any public signs of trouble with the partnership. The token is now valued at zero.

Token buyers have claimed they were cheated by Yahui Zhou and that StarMaker should make good on their losses. Zhou has stated that the claims are baseless and has subsequently distanced himself from the project. Opera’s most current financial statements have begun to disclose the potential for litigation relating to the StarMaker crypto currency partnership. [Pg. S-25]

All told, we find the nature and timing of Opera’s $30 million related-party karaoke app investment to be unusual. At best, it raises questions about the Chairman/CEO’s judgement relating to this crypto karaoke misadventure.

More Related Party Transactions: Why Has Opera Directed Over $31 Million, (Including an Advance of $18 Million in Cash) to AntiVirus App Maker 360 Mobile Security for Help with Its Facebook & Google Ads?

Usually, when a company wants help with its marketing, it hires a marketing company.

Contrary to what’s typical, Opera has instead directed over $31 million of marketing cash to another of Chairman/CEO Yahui Zhou’s related companies, 360 Mobile Security.

Opera has had a marketing relationship with 360 Mobile since mid-2016, when a deal to acquire Opera by current management was already in the works. The agreement called for 360 Mobile Security to negotiate and manage its advertising/media services.

360 Mobile Security describes itself as a security company. We could find no other examples of the company acting as an advertising agency. We reached out to 360 Mobile to ask whether it had any other marketing clients and have not heard back as of this writing.

The original service agreement had billed Opera at an annualized rate of about $10 million.

That rate seems to have stepped up considerably as of late. Two months after Opera’s IPO, flush with investor cash, an amended agreement called for a prepayment of $10 million to 360 Mobile Security.

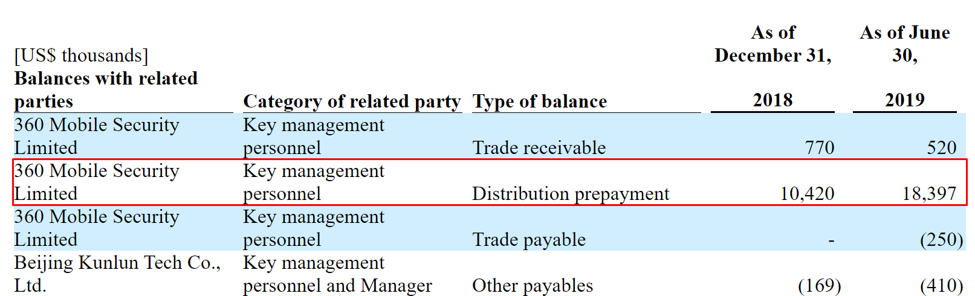

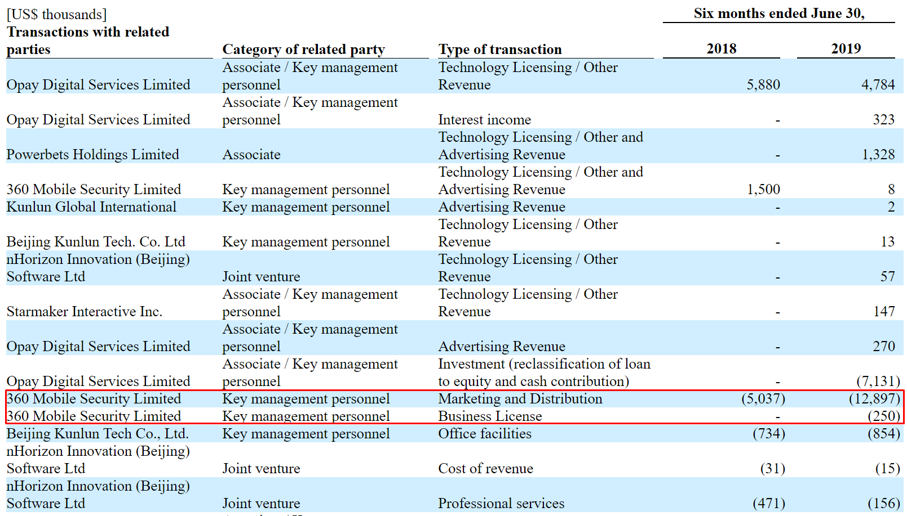

That prepayment has steadily increased, with $18.4 million in prepayments due to the related-party as of Opera’s September 2019 secondary offering prospectus [Pg. F-17]:

The same prospectus indicates that Opera has paid out almost $13 million of marketing and distribution expenses to 360 Mobile Security in the first half of 2019.

We find this combined $31 million in cash out the door in expenses and prepayments to be concerning, and raises further questions for us about Opera’s cash payments to related parties.

To Summarize: Opera’s Cash-Bleeding Related Party Transactions

- $9.5 million to buy an entity that appears to have been owned 100% by Opera’s Chairman/CEO, despite corporate disclosures stating otherwise, to own a business that was already funded and operated by Opera.

- $30 million invested into a karaoke app business owned by Opera’s Chairman/CEO, days before the arrest of its key partner, an ICO backed and supported by Opera’s Chairman/CEO. Opera has an “option” to invest another estimated $49 million into the app in 2H 2020.

- $31+ million in cash for marketing expenses and prepayments, not paid to an advertising agency, but to a related-party antivirus software company with no other known marketing clients.

Opera Appears to Be Quietly Restating Past Revenue, Making Current Results Appear Better, Without Disclosing It

Beyond questioning Opera’s related party transactions, we also noticed some issues with the company’s reported financials.

When numbers from prior periods start to suddenly move around without explanation it suggests there could be an internal controls issue. Most companies that restate financials provide detail on restatements in order to assure investors that any mistakes or issues won’t happen again.

Opera has seemingly taken a different approach. Over the past several quarters, the company has apparently restated past financials without disclosing why. The result has been that year over year and quarter over quarter numbers have appeared better than otherwise.

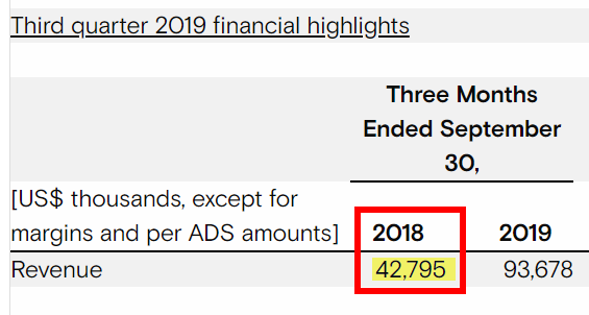

Take, for example, the most recent Q3 2019 quarter. Opera reported that Q3 2018 revenue was $42.795 million:

But when we checked the Q3 2018 numbers reported at the time, we see that revenue had actually been $44.7 million. Where did the other ~$2 million go?

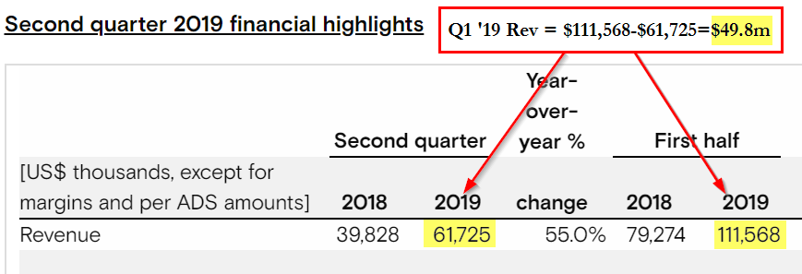

In another example, in Q2 2019, Opera reported $49.8 million of revenue in Q1 2019.

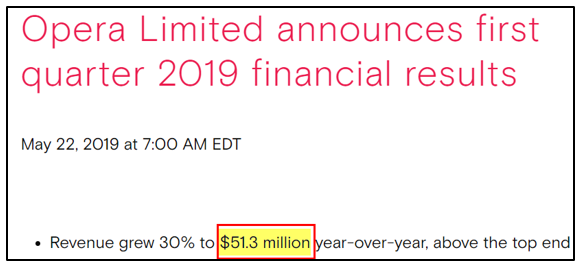

But when we checked the Q1 2019 numbers reported 3 months earlier, we see that revenue had actually been $51.3 million:

In both cases, the revising down of the previous period made the year over year and quarter over quarter growth rates more impressive on the headline numbers.

We checked to see if any recent accounting changes could have been applied retroactively and been the source of these silent restatements. The company has adopted several accounting methodology changes as of January 1, 2018, but none appear to influence the revenue numbers from Q1 2018 and beyond. [Pg. F-20]

We contacted Opera investor relations about the quiet restatements. IR had no explanation for the restatement of the Q3 ‘18 numbers but said they would get back on the specific reason.

The Q2 ’19 restatement was explained as follows:

“We changed our methodology as it related to microlending once we had more data. In Q1 we recognized 100% of late fees. The data showed us that about a minority of late fees are recoverable, so in Q2 we started recognizing only what our historical data showed we could recover.”

We appreciate the answer from Opera, but we think these types of changes should be disclosed to investors without the need for prompting.

We also think this answer shows that the lending segment may be employing aggressive revenue recognition practices. To recognize 100% of late fees as revenue suggests that every late borrower, no matter how impoverished, would be able to pay back late fees at a rate of 730%+ per annum. This is obviously an absurd notion given the massive loan default rates, and makes us question the revenue/default recognition methodologies in the overall segment.

Conclusion: A Turnaround “Story” That Is Little More Than a Story

Opera’s deteriorating legacy business, declining financials (except revenue), bizarre business pivot, and related party transactions suggest to us that we may not be witnessing the miraculous “turnaround” story that the company would want investors to believe.

We believe Opera’s foray into predatory microlending – a business that has already led Qudian shareholders to over 80% losses since the company’s IPO – will result in a tab that will also be coming due soon for Opera shareholders.

We also believe that Google, once it realizes the abuses that it is (likely inadvertently) facilitating, will eventually curtail or eliminate Opera’s lending practices.

Beyond witnessing the ‘microfinance’ playbook in Qudian’s collapse, we’ve also seen a litany of other US listed China based management teams engaging in extensive related party transactions. In many cases, insiders are able to enrich themselves while the result is far less favorable for shareholders.

Put simply: We feel like we’ve seen this opera before – and the final act ends poorly for shareholders.

Disclosure & Legal Disclaimer

Disclosure: We are short shares of Opera

Additional disclaimer: Use of Hindenburg Research’s research is at your own risk. In no event should Hindenburg Research or any affiliated party be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information in this report. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities covered herein. You should assume that as of the publication date of any short-biased report or letter, Hindenburg Research (possibly along with or through our members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or consultants) along with our clients and/or investors has a short position in all stocks (and/or options of the stock) covered herein, and therefore stands to realize significant gains in the event that the price of any stock covered herein declines. Following publication of any report or letter, we intend to continue transacting in the securities covered herein, and we may be long, short, or neutral at any time hereafter regardless of our initial recommendation, conclusions, or opinions. This is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. Hindenburg Research is not registered as an investment advisor in the United States or have similar registration in any other jurisdiction. To the best of our ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the stock covered herein or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Hindenburg Research makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Hindenburg Research does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein.

385 thoughts on “Opera: Phantom of the Turnaround – 70% Downside”

Comments are closed.

Great note. What % do management own? (65?) Have they sold any since IPO? What is the float ex management and top 5 institutional holders?

Wonderful staff, assuming Google will ban them ASAP, what prevents them from opening a new co under Opera with different brand and offer the same loans. i.e. Google won’t know that until someone will let them know and then the same drill

Edgium browser zone

I use Opera to reduce mobile traffic

This is awesome

Great article! Wonderful collection

Great reading this article.

Thanks for sharing.

Great Research!

Great reading this article.

Great article

Wow, cool post. I’d like to write like this too taking time and real hard work to make a great article.

amazing article and nice information thanks for this amazing information we are waiting for the new articles.

Great article! Wonderful collection

So fantabulous, thanks for the post, you guys have done well. I would like to visit here again

Awesome post.

OPay, Opera’s African fintech startup, has confirmed that the company will shut down some of its businesses. This includes a B2C and B2B eCommerce platform, OMall and OTrade respectively, a food delivery service; OFood, a logistics delivery service; OExpress as well its ride-hailing service, ORide and OCar.

Great and Enlighten… Thanks for sharing.

Nice post

Nice post plus amazing content

amazing article thanks for this amazing information

Great and Enlighten… Thanks for sharing

Thank you for a great way to get traffic and links. I’ve hear good things about your from Richard Legg. Your list is excellent! I have an https://www.hightime420.shop/

and I can clear blockages to a person success. Sounds strange? Check it out! Am sure you will like it.

breifly explained every thing and knoweldge is up to date.

Winderful art of sharing and providing best knowledge to readers

What an awesome post. Thanks for sharing

Finally got the information which I want. Thank you so much dear for sharing this, visit NaijaRetro for all round entertainment

one of the best information available on the web regarding the topic. If want to know the difference between the Facebook and Facebook lite visit the post https://www.thesolutionnation.com/know-the-difference-between-facebook-and-facebook-lite/

Winderful art of sharing and providing best knowledge to readers

nice post here

Nice

DISTINCTVALUED RESEARCH PROJECTS

nice post Project Topics/Materials

nice post Project Topics/Materials

thanks for sharing good information.

Thank you for sharing great content

Thank you so much for sharing information , nice post

Remarkable turnaround.

I really love this article and I have learnt a new thing here today.

Wow this is so amazing

Thanks for your nice sharing Information..

regards from Indonesia

Good article, but it would be better if in future you can share more about this subject. Keep p`osting

Good article, but it would be better if in future you can share more about this subject. Keep p`osting

Wow this is so amazing

WOW i really like this article

Well knowledge that you provide, one of my well experience

If there are no consequences for screwing up, then people will keep screwing up.

Thanks for sharing.

Great Research!

Anna Lena