- Ebang is a China-based crypto company that has raised ~$374 million from U.S. investors in 4 offerings since going public in June 2020.

- While the company represented that it would use the majority of its numerous capital proceeds to develop its business operations, our research discovered it instead directed much of the cash out of the company through a series of opaque deals with insiders and questionable counterparties.

- For example, the company directed $103 million, representing ~$11 million more than its entire IPO proceeds, into bond purchases linked to its U.S. underwriter, AMTD, which has a track record including (a) fraud and self-dealing allegations levied against it by one of the largest private equity firms in China and (b) listings that have subsequently imploded.

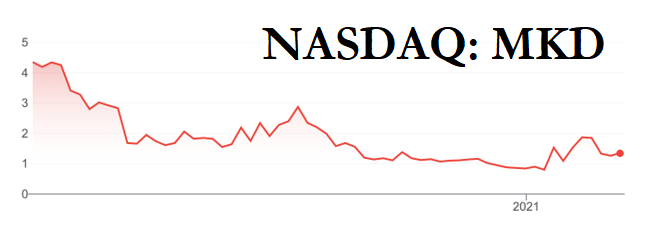

- AMTD entered into similar bond transactions with another company it recently took public in January 2020 called Molecular Data. That company is down 70% since then, has seen 6 board members and its co-founder resign, and had its auditor decline to stand for re-election.

- In November 2020, Ebang tapped the market for its first secondary offering, announcing a $21 million raise. It claimed proceeds would go “primarily for development”. Around the same time, the company directed $21 million to repay related-party loans to Ebang Chairman/CEO Dong Hu’s relative.

- Before going public on NASDAQ in June of 2020, Ebang twice applied for a listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, attempting to raise as much as $1 billion. Multiple media outlets reported that Ebang’s Hong Kong IPO plans were suspended following involvement in an alleged sales inflation scheme with a company called Yindou.

- Yindou was a massive Chinese peer-to-peer online lending scheme that defaulted on its 20,000 retail investors in 2018, with $655 million “vanish(ing) into thin air”. Its ultimate beneficial owner “fled the country”, and Chinese prosecutors have been pursuing a criminal case against other suspects associated with Yindou.

- Ebang claims to be a “leading bitcoin mining machine producer”, yet our research indicates this extraordinary claim is backed by no evidence. Ebang released its final miner in May 2019 and has since seen its sales dwindle to near-zero, delivering only 6,000 total miners in 1H20.

- With its mining machine business failing, Ebang pivoted the story to a cryptocurrency exchange launch called “Ebonex”. Announcements about the exchange added as much as $922 million market capitalization to Ebang.

- We found that Ebang’s exchange appears to be purchased from a white-label crypto exchange provider called Blue Helix that offers out-of-the-box exchanges for as little as no money up-front.

- Ebonex reports what appears to be fictitious volumes. Despite just launching and having virtually no online presence, Ebonex volume data implies it is one of the largest spot exchanges in the world. Its trading metrics are absent from crypto exchange trackers such as FTX and CoinMarketCap.

- Ebang is yet another cautionary tale for inexperienced retail investors enthused by anything crypto-related. As is so common with other ridiculous China-based schemes, the company will likely keep selling shares as long as investors are willing to keep buying them. We think this is a clear one-way street, and the capital isn’t coming back.

Initial Disclosure: After extensive research, we have taken a short position in shares of Ebang International Holdings Inc. This report represents our opinion, and we encourage every reader to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report.

Background: Ebang Is Simply The Latest Chapter In The “China Hustle” Disguised As A Bitcoin Mining Play

Stocks tied to blockchain technology have been on the run over the last few months, swept up in bitcoin’s resurgence. Ebang has been able to ride this wave, going public in June 2020 largely based on claims of being a leading global producer of bitcoin mining machines.

Since going public, the company has announced a series of preliminary initiatives, such as setting up various international entities (1,2,3,4), launching bitcoin, litecoin, and dogecoin mining businesses, and launching a new crypto exchange.

These preliminary achievements have been enough for investors to award the company a market cap as high as $1.5 billion, and have paved the way for a slew of follow-on equity offerings at prices ranging from $5.00 to $6.10 per unit, including warrants. In total, the company has raised ~$374 million from investors in 4 offerings over the past 9 months.[1] [Pg. 4, 5, and Pg. 83]

Investors in Ebang likely think they are getting in on the ground floor of an expansive, multi-pronged cryptocurrency technology enterprise. But our research found that while the company represented that it would use the majority of its numerous capital proceeds to develop its business operations, it instead simply directed cash out of the company through a series of opaque deals with entities linked to its Chairman/CEO and its underwriter.

For example, the company directed $103 million, representing ~$11 million more than its entire IPO proceeds, into bond purchases linked to its underwriter, AMTD, which has a track record of (a) fraud and self-dealing allegations levied against it by one of the largest private equity firms in China and (b) listings that have subsequently imploded.

The company then announced a $21 million secondary offering, claiming it would use the funds to expand its operations. However, we found that the company directed $21 million to a relative of its Chairman/CEO around the same time.

These actions shouldn’t surprise investors familiar with Ebang’s history and abysmal reputation in China. Prior to going public in the U.S., Ebang was accused of using cash embezzled from a fraudulent lending scheme in order to inflate its sales in the run-up to its planned Hong-Kong IPO.

The company ultimately failed to list in Hong Kong, twice, owing to customer lawsuits, police investigations relating to embezzlement and other fraud allegations, and public scrutiny over its conduct.

Following these failures, Ebang was finally brought public in the U.S. by underwriter AMTD, with the track record mentioned above.

Rather than an exciting opportunity, we believe Ebang is simply yet another “China Hustle”; the latest in a long list of companies blatantly absconding with U.S. capital, which winds up taking a one-way trip to China as a result of misrepresentations to U.S. investors.

Background: Ebang’s Crypto Mining Hardware Business And Recently-Opened Crypto Exchange

Ebang was founded by its current Chairman and CEO, Dong Hu, in 2010. The company initially focused on selling communications network access equipment until around 2014, when it transitioned into the blockchain industry. [Pg. 10]

Ebang launched its first application-specific integrated circuit (“ASIC”) mining machine, called the Ebit E9+, in December of 2016. [Pg. 119] ASIC machines are specifically built to mine certain cryptocurrencies like Bitcoin, Dash, Litecoin and Zcash. Since then, the company has launched 12 new machine variations, with the most recent being the machine seen below, the Ebit 12.

In addition to crypto mining hardware, the company recently launched a crypto exchange and began mining bitcoin on its own books in 2021.

Part 1: Before Its Nasdaq Listing, Ebang’s Fraud Allegations Led to Two Failed Hong Kong IPO Attempts

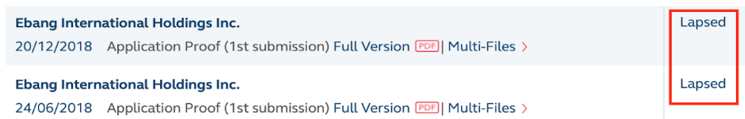

Before going public on NASDAQ in June of 2020, Ebang twice applied for a listing on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange, reportedly attempting to raise as much as $1 billion. Both times, that applications lapsed without approval.

Ebang’s Hong Kong IPO Was Suspended Following Allegations Of Sales Inflation and Involvement With a Ponzi Scheme

Multiple media outlets reported that Ebang’s Hong Kong IPO plans were suspended following involvement in an alleged sales inflation scheme involving a company called Yindou. [1,2,3]

Yindou 银豆网[2] was a Chinese peer-to-peer online lending platform. According to media reports, Yindou’s platform offered short-term investments, usually with a one-year term, promising a 13% return. Below is a screenshot of its website, from February 24th, 2018 advertising 13% returns for 376 days.

In July 2018, Yindou reportedly defaulted on its 20,000 retail investors, failing to pay back amounts totaling as much as RMB 4.4 billion (USD $676 million). Its ultimate beneficial owner then “fled the country”. Chinese prosecutors have been pursuing the case against other suspects associated with Yindou.

Prior to its implosion, Yindou’s principals allegedly engaged in wash sales transactions with Ebang ahead of its IPO in order to create the false appearance of sales.

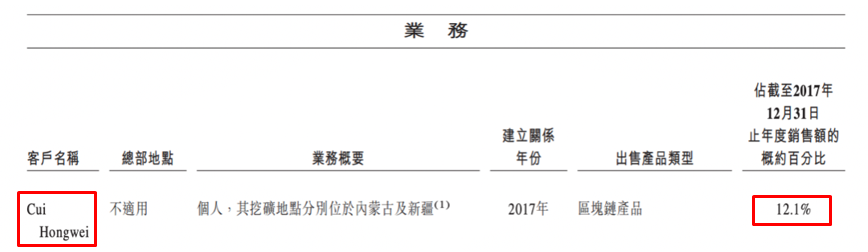

Local media reported that the spouse of Yindou’s CFO, Cui Hongwei 崔宏伟, transferred ~RMB 520 million (USD $79.9 million) to Ebang between December 2017 and February 2018. Ebang then transferred RMB ~380 million (USD $58.4 million) back to Cui Hongwei several months later, between March and April 2018.

It is unclear when the transactions began, but Yindou’s CFO’s wife was listed on Ebang’s IPO prospectus published in December 2018 as a customer who generated 12.1% of Ebang’s 2017 sales revenue. [Pg. 152]

Yindou Had Directed $79.9 Million To Ebang, Via Accounts Linked To Yindou’s CFO’s Wife, According To Chinese Media

The Funds Were Alleged To Have Been Used To Inflate Ebang’s Sales Ahead of Its IPO

Yindou investors, looking to recover their investments, went to Ebang headquarters in Hangzhou to demand that Ebang return the money owed to them.

Ebang subsequently stated that Cui Hongwei was a customer and claimed (a) that the RMB 520 million (USD ~$79.9 million) was payment for its products (mining rigs), (b) that it had returned RMB 380 million (USD ~$58.4 million) of the initial payment, and (c) that it would not return the remaining part (RMB 140 million or USD ~$21.5 million) because the products had been delivered.

Yindou Investors Asked Hong Kong Regulators To Refuse Ebang’s Listing Application Due To The Alleged Embezzlement

Yindou’s investors were angered to see Ebang’s subsequent attempt at going public in Hong Kong.

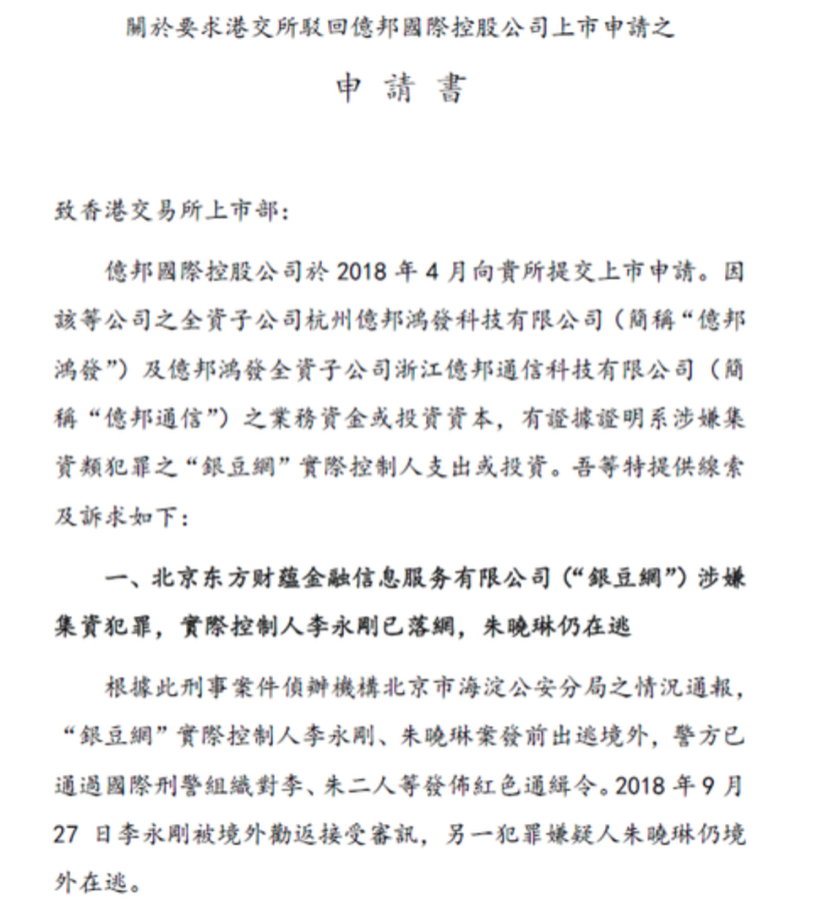

Below is an October 12, 2018 screenshot from a letter sent to the Listing Department of the Hong Kong exchange asking authorities not to accept Ebang’s listing application.

The letter is titled “Application to request the Hong Kong Stock Exchange deny Ebang’s IPO application”. It states that there is evidence that capital used in Ebang’s transactions or investment activities were provided from Yindou, a beneficiary of “illegal fundraising”.

Around 3 months later, Ebang’s Hong Kong IPO listing lapsed for the first time. Ebang reapplied in December 2018, but its application suffered a similar fate to its first, lapsing again.

Part 2: Ebang Then Took To The U.S., Where It IPO’d Through An Underwriter Accused Of Fraud By One of Its Largest Investors.

Its IPO Proceeds Since Vanished

Shunned From Hong Kong, Ebang Set Its Sights on US Markets, and Raised $91.7 Million Through a June 2020 IPO

Ebang was finally able to raise funds through a U.S. IPO in June 2020, then immediately diverted the IPO proceeds outside of the company in a series of highly irregular transactions.

Many of the transactions can be tied to the Hong Kong-based underwriter who led Ebang’s IPO, named AMTD. As we show, AMTD has faced a history of fraud and self-dealing allegations (including from one of China’s largest private equity firms), as well as a track record of U.S. IPO flops.

Ebang Represented in Its IPO Prospectus That the Vast Majority of the Proceeds Would Go Into Expanding its Business, And that Any Loans Made With Proceeds of the Offering Would Only Go to Its Subsidiaries

On June 26, 2020, Ebang went public in the US by listing on NASDAQ. The company raised net proceeds of $91.7 million [Pg. 5]. In Ebang’s IPO prospectus it told investors that ~70% of the newly-raised capital would be used for purposes related to expanding its business, development and introduction of new mining machines, corporate branding and marketing. The rest was to be allocated to general corporate purposes. [Pg. 59]

Further, Ebang promised that any loan proceeds would only be used to make loans or capital contributions to its PRC (China) subsidiaries. [Pg. 59]

“As an offshore holding company, under PRC laws and regulations, we are only permitted to use the net proceeds of this offering to provide loans or make capital contributions to our PRC subsidiaries.”

Despite These Claims, Ebang Promptly Diverted $103 Million (All of Its Newly Raised IPO Cash And Then Some) Into Bonds Linked to Its Underwriter, AMTD

Rather than following through on its representations to investors, Ebang used its IPO funds to purchase long-term bonds tied to its underwriter, AMTD, in a series of highly irregular transactions.

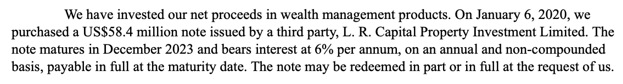

Less than a week after Ebang’s June 2020 IPO, it loaned $40 million directly to the controlling shareholder of AMTD, LR. Capital Property Investment.

Days later, it began directing what would amount to $63.6 million into two bond purchases from a Cayman-based entity linked to AMTD, called International Merchants Holdings. [Pg. F-49][3]

The original $40 million bond was redeemed as of an undisclosed date, while the other $63.6 million seems to remain outstanding. Based on the company’s last available balance sheet, this sum would represent its single largest balance sheet asset. [Pg. 74]

Note that the bonds have maturities ranging from 2023-2025, which could tie the capital up for years at interest rates ranging from only 4.0%-6.8%. In other words, rather than using the capital to expand its business, as originally claimed, Ebang has apparently tied it up in low yielding, long-term bonds backed by an opaque Cayman-based issuer.

Ebang’s Underwriter, AMTD, Has A History Of Allegations Of Fraud, Self-Dealing And IPO Flops

We think this surprise use of funds bodes poorly for Ebang’s investors given AMTD’s history as a counterparty.

For example, AMTD and its chairman, Calvin Choi, have recently been accused of multiple forms of “financial fraud” by one of largest private equity firms in China.

An article from October 2020 in Nikkei details some of the accusations:

In the article, major Chinese private equity firm CMIG, which invested with AMTD, explained how its money essentially disappeared. According to one senior executive quoted in the article:

“Some projects made money, but he didn’t give us the profits. Some had losses, but we don’t know whether he truly invested or misappropriated the money.”

They vowed to “send Choi to jail” if he didn’t return their funds.

According to media outlet Caixing Global, CMIG hung banners of AMTD Chairman Calvin Choi in Hong Kong, accusing him and his father of fraud in the months leading up to Ebang’s suspicious bond purchases.[4]

The banner reads:

“Financial Fraud – Calvin Choi, Father and son worked together to steal massive amount of capital from stock investors. Ironclad evidence shows Calvin Choi scammed my money. Investors lost everything. US-listed HKIB, Singapore-listed HKB. Stock Fraud. Please confess to Securities and Futures Commission and Independent Commission Against Corruption.”

Following some of these allegations, Choi put out a bizarre, meandering statement:

“I have encountered many things that have been questioned and incomprehensible by the outside world. What is more, there are those who envy and jealous (sic), and those who are cold-eyed and mockers, and malicious. There are slanderers.”

AMTD Has Done This Before: Another Company It Took Public in 2020 Directed IPO Proceeds Back to Them

That Company Is Down 70%, Has Seen 6 Board Members And Its Co-Founder Resign, And Saw Its Auditor Decline To Stand For Re-Election

China-based Molecular Data Inc (MolBase) listed on Nasdaq in January 2020. AMTD led the $70 million IPO.

In similar fashion to Ebang, Molbase directed $58.4 dollars to AMTD’s parent, L.R. Capital, when it received its IPO proceeds [Pg. 131].

Molbase has exhibited major issues of its own. The company has seen six Board resignations (1,2,3,4,5,6), its co-founder resign, it was late on its 20-F and its auditor declined to stand for re-election.[5] Molbase is down almost -70% since its IPO.

AMTD’s Track Record As an Underwriter is Abysmal. Despite the Bull Market, 87% of Its U.S. IPOs Have Resulted in Losses

Despite a sustained bull market, 87% of AMTD’s U.S underwritten IPOs have resulted in substantial losses for investors. Within about 2 years from listing, AMTD’s U.S. IPOs have plummeted a median 48.7% and an average of 34%.

Ebang directing almost the entirety of its IPO proceeds into the bonds of an obscure company, related to an underwriter with a dubious history, comes off as nothing short of highly irregular behavior.

With Its IPO Cash Gone, Ebang Raised $21 Million Through A Secondary Offering To Be Used “Primarily for Development”

Around the Same Time, $21 Million Went to Pay Back Related Party Loans to the Chairman/CEO’s Relative

With essentially all cash proceeds from its IPO directed back to its underwriter, Ebang was almost immediately short on cash.

In November 2020 it tapped the market for its first secondary offering, announcing a raise of $21 million.[6] In the press release, the company provided the following explanation for how it would use the proceeds:

“The Company intends to use the net proceeds from the offering primarily for development and application of blockchain technology into financial services, sourcing core intellectual properties relating to its businesses, corporate branding and marketing activities, and general corporate purposes, which may include working capital needs and other corporate uses.”

Despite these representations, we see from a prospectus filed just weeks earlier that the company used $21 million to repay related-party loans to its Chairman/CEO Dong Hu’s relative.[7]

Part 3: Ebang’s Business Operations In Mining, Or Lack Thereof

Ebang Claims It Is A “Leading Bitcoin Mining Machine Producer” And That, In 2019, It Was “The Leading Bitcoin Miner In The Global Market”

In press releases, Ebang consistently claims to be a leading bitcoin mining producer globally. See a recent February 17, 2021 example here:

This claim is repeated on Ebang’s prospectus and virtually every filing the company has issued. [E.g.: Pg. 2]

According to Ebang’s website, it was the leading bitcoin mining manufacturer in terms of hash rate sales in 2019, putting it above well-known industry competitors such as Bitmain.

Our research indicates this extraordinary claim was backed by absolutely no evidence.

Ebang Is Not The World’s Leading Bitcoin Mining Machine Producer. In Fact, It Has Sold A Pittance Compared To Other Large Chinese Producers.

A far larger competitor called Bitmain controls around 65% of the bitcoin miner market in terms of hash rate in 2019. Bitmain is currently private and doesn’t disclose its precise numbers.

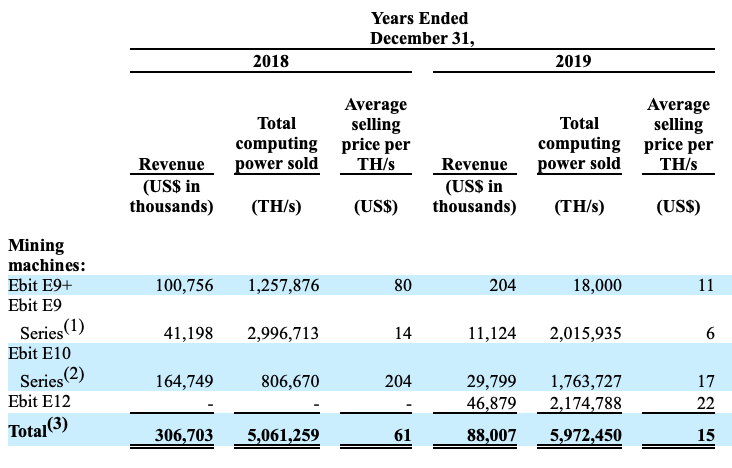

However, Ebang’s prospectus discloses a breakdown of its annual sales and makes clear that it isn’t even #2. Terahashes per second (TH/s) is a key measure of a mining machine’s processing power. [Pg. 86]

For 2019, the company sold total computer power of 5.97 million TH/s in 2019, at an average price of $15 per TH/s.

From these disclosures it is evident that Ebang is not the leading mining machine producer in terms of hash rate sales. Chinese competitor MicroBT sold 6x what Ebang sold in 2019, 600 thousand units, at an average of 60 Th/s per unit at almost double the price per TH/s.

In An Industry Scorching Hot With Growth, Ebang’s Miner Sales Have Been In Decline Since 2018 And Are Now Close To Zero

Ebang notes in its prospectus that from 2015, to 2019 the mining machine market has grown at a 61.3% CAGR.

“Sales of Bitcoin computing hardware, the majority of which comprise sales of Bitcoin mining machines, have surged at a CAGR of 61.3% from approximately US$0.2 billion in 2015 to approximately US$1.4 billion in 2019 and are expected to further increase at a CAGR of 24.8% to approximately US$4.3 billion in 2024, according to the F&S report.” [Pg. 1]

Yet Ebang doesn’t seem to be participating in this fast-paced growth.

Ebang had its best year in 2018, when it sold 415,930 units at an average selling price of $737. Ebang’s first half 2020 numbers imply it is on track to sell 11,588 units, a ~97% decline. Ebang’s average selling price per unit during the first half of 2020 was $775.

Of The Limited Sales Ebang Has Reported To Date, Many Appear to Be Defective Units or Just Fabricated Altogether

Example 1: In 2018, a customer called Beijing Mobcolor Alleged in a Lawsuit that an Ebang Director Asked Them to Fake a $15 Million Purchase Through a ‘Round-Trip’ Transaction

Ebang was alleged to have engaged in yet another scheme to book fake sales in the run up to its Hong Kong IPO, according to a Chinese court judgment.[8]

Customer Beijing Mobcolor asserted that a director of Ebang, Zhang Hao (章昊), called an executive of Beijing Mobcolor, Gu Hongliang (谷红亮), in November 2018 and told Gu Hongliang that Ebang was listing in Hong Kong and needed USD $1.5 million to “balance its books.” The two individuals had been classmates, according to local media reports.

Beijing Mobcolor asserted in its lawsuit that Ebang would arrange the payment of USD $1.5 million through a third party, which it would then use it to pay Ebang. The Ebang director asked Beijing Mobcolor to sign a “Letter to Apply for Delayed Payment (延期付款申请函)” for around USD $15 million, which would represent a remaining payment for a purchase order of 100,000 mining rigs.[9]

Example 2: In the lead up to its NASDAQ IPO, Ebang claimed in a press release that it had a $100 million order from a company called Madison Holdings. Madison Holdings only had ~$5.9 million in available cash around the time and mainly sold alcohol products.

In October 2019, Ebang publicized a $100 million dollar order from Madison Holdings (8057 HK), a company that “retails and wholesales alcohol products”, mainly red wine, but recently got into blockchain last year when it purchased part of exchange Diginex Limited.

At the time of the announcement, Madison Holdings was a penny stock trading on the Hong Kong Exchange at ~24 cents. It had unsegregated bank balances of US ~$5.9 million on September 30th 2019, according to its financials. [Pg. 6]. Madison’s Hong Kong filings stressed that the deal was “non-legally binding”. Madison ultimately sold its crypto currency business 3 months later in January 2020. [Pg. 13]

Ebang Had a Reputation For Delivering Defective Products

Example: Chinese Media Reported That An Order of 500 E10 Miners Needed 873 Repairs In Three Months

While not well covered in the US media, extensive product issues at Ebang have been covered in Chinese media.

A slew of lawsuits against Ebang’s Chinese subsidiary suggest that the machines Ebang was able to deliver resulted in disputes. Chinese corporate information site QCC references at least 10 different judgement documents.

As one example, according to a 2019 lawsuit by miner Ma Xiaoyun, 500 E10 Ebang miners he purchased were so defective that they started malfunctioning immediately, and ultimately required 873 repairs in just three months. That lawsuit presented a live recording of Ebang Vice President Zhang Hao admitting the E10 miners had a high failure and repair rate.

Ebang refuted the claims, claiming the purchaser was responsible for the failures. The case appears to have resulted in a partial win for the purchaser, Xiaoyun, who received compensation for the miners’ late arrival but not for the equipment itself.

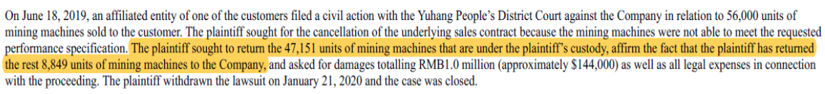

Ebang’s prospectus disclosed another case where plaintiffs demanded to return over 47,000 machines. [Pg. F-26]

We interviewed former employees that corroborated the quality issues. A former employee in Zhejiang who was with the company for 3 years told our local investigator that the brand had declined significantly:

“Now Ebang equipment is basically famous for being awful. The reputation is completely gone. Sales of miners are really bad.”

Collectively, these well-publicized customer issues have contributed to Ebang’s miner business decline in advance of its U.S. IPO. Given the well-resourced and credible competition in the space, we don’t expect a revival to Ebang’s deflated mining operations.

Ebang likely came to the same conclusion and subsequently decided to pivot to developing its own cryptocurrency exchange. Our research suggests this is just the latest doomed initiative to justify raising more cash from investors.

Part 5: Ebang’s Crypto Exchange

On March 11th, Ebang Announced The Start of Beta Testing For A Crypto Exchange, Sending Shares Surging

The Price Spike Implied a $900 Million Value to the Beta Exchange

On March 11, 2021 Ebang announced it would start beta testing on March 15, and launch a cryptocurrency exchange by the end of the month.

In the following days, Ebang’s enthusiastic investors sent the stock soaring as much as ~77%, adding ~$922.7 million to its market cap, from a close of $6.88 on March 10th, to $12.25 five days later.[10]

The launch didn’t happen by the end of the month. Instead, on April 1st, the company announced it had raised another $85.4 million through another secondary offering. On April 5, 2021, the company announced the “official launch” of its cryptocurrency exchange.

Ebang’s Chairman Claimed That The Successful Crypto Exchange Launch Was Due To The Company’s Extensive Investment in R&D

In the press release celebrating the official “Ebonex” exchange launch, Chairman and CEO Dong Hu claimed that the milestone was a result of Ebang’s continuing investment in R&D.

“The official launch of our cryptocurrency exchange is the result of our continuing investment in research and development. In recent years we have made a considerable investment in R&D talent recruiting, as well as product innovation and iteration.”

But Evidence Shows Ebon Simply Purchased a White Label Out-Of-The Box Crypto Exchange And Made Minor Modifications

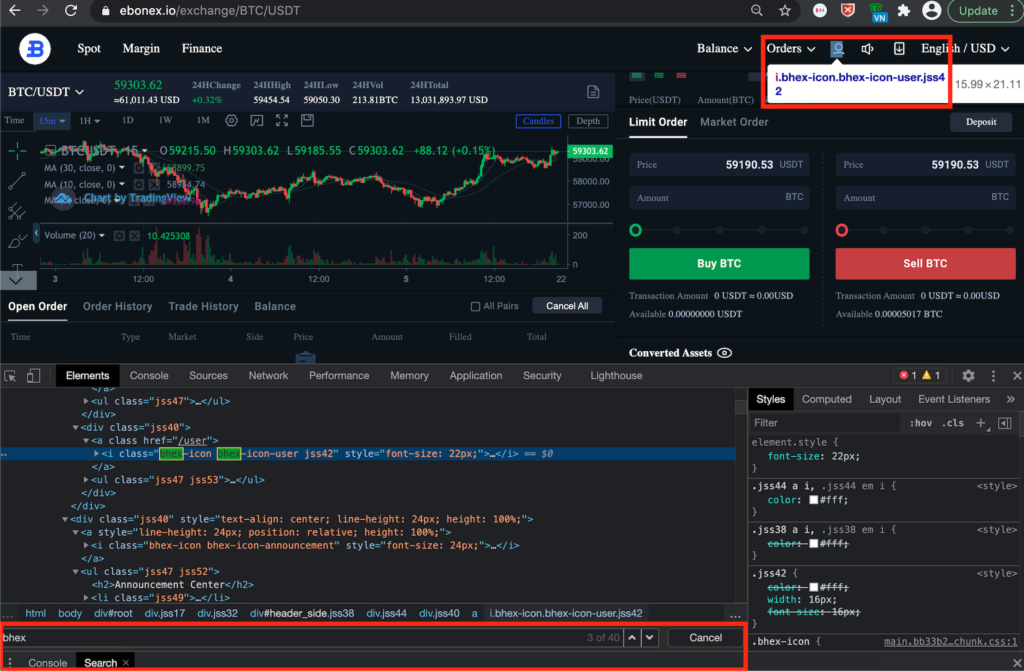

Our review of Ebang’s “Ebonex” crypto exchange immediately turned up irregularities. In particular, Ebonex’s source code repeatedly references “Bhex”, an exchange closely affiliated with Blue Helix.

Blue Helix is an Asia based Crypto Exchange and provider of white label crypto exchange software. The company counts a large exchange called Houbi as an investor and reports having over 270 clients.

Blue Helix has advertised white-label exchange solutions for as little as zero upfront cost.

Below is a screenshot of Ebonex’s exchange taken on April 5th, 2021. It looks almost identical to Blue Helix’s platform.

Below is Blue Helix’s spot trading interface shown on its website for comparison:

In fact, when reviewing the Ebonex exchange, we see the logos on the top right of the page are the exact same as Blue Helix’s.

Ebonex’s source code even reveals that the logos are literally labeled Bhex, which is the Blue Helix-affiliated exchange. We found a total of 40 references to Bhex on just one spot trading page shown below.

Unsurprisingly, Ebonex looks strikingly similar to two Blue Helix related exchanges as well. Both exchanges, HTBC (an affiliate that Blue Helix’s domain now redirects) and Huobi, appear to be almost identical.

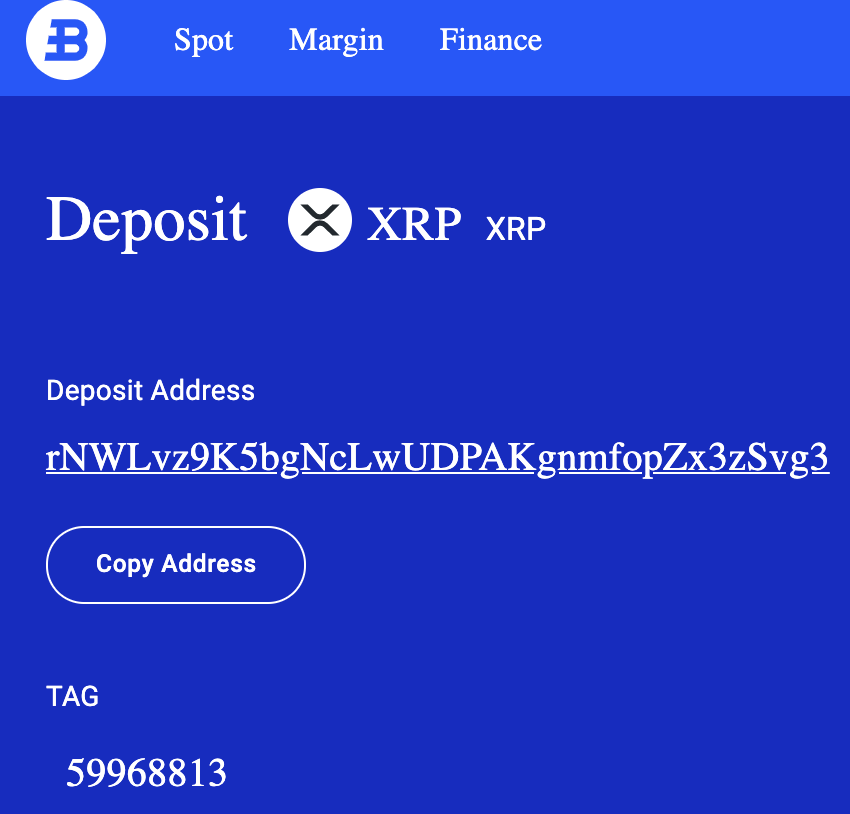

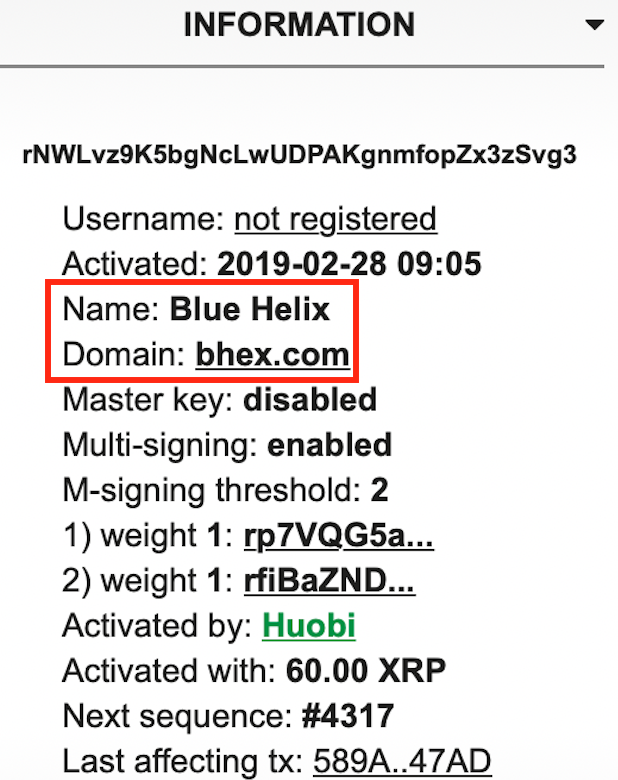

Beyond design, Bhex.com is also apparently where the money is being sent, in what may be a surprise to users. When we set up an account on Ebonex to test the site, we found that the XRP address used to deposit tokens on Ebonex’s platform led to an XRP domain associated with Blue Helix. Below is the deposit address we were shown that would allow us to transfer XRP onto Ebonex:

When running a search for the specific address on an XRP chain explorer we found it belongs to Blue Helix.

In sum, it appears that Ebonex’s exchange is simply a mildly customized out-of-the-box white label solution built by another provider, with the money being stored by that provider.

Ebang’s Ebonex Exchange Reports Incredibly Suspicious Volume Metrics, Suggesting That the Day-Old, Relatively-Unknown Platform is Already on Par With the Largest Crypto Exchanges in the World

Already we are seeing red flags with Ebonex’s platform, including massive 24-hour trading volume Ebonex displayed on the day of its launch.

For instance, Ebonex shows 24h volume of the ETH/BTC pair at $243 million (115319 ETH at $2,114 each). Around the same time, Coin Marketcap showed a total ETH/BTC volume of only $60 million at Huobi Global, the second largest crypto exchange globally. Coinbase Pro only transacted around $28 million for the same pair.

We don’t think there is any way that Ebonex is trading this volume itself given its limited web and social media footprint. Ebonex currently only has around 1.8 thousand Twitter followers, 1.3 thousand Facebook followers and 14 Telegram members. Google Trends displays near-zero search interest. Compared to other exchanges, Ebonex’s volume does not reconcile.[12]

Ebonex is also absent from all major crypto exchange trackers we reviewed, including FTX and CoinMarketCap. This is a major red flag.

Late To The Party By About 9 Years: The Exchange Space Is Highly Competitive With Roughly 500 Existing Exchanges

Market Share Is Going to Established Players

With an estimated 500+ crypto exchanges, Ebang is late to a crowded market.

Industry consulting firms that advise groups wishing to build exchanges estimate it costs about $300-$500 thousand to set up a crypto exchange, representing a very low barrier to entry.

Daily volume trends show that the top exchanges command a disproportionate share of the trading volume. A February 2021 industry report estimated that 85% of the volume was done by roughly 84 firms considered “top tier”. [Slide 22]

Companies Like Coinbase, Kraken And Bitfinex Have Each Spent Almost A Decade Developing Brands And Trust With Customers

Will the Crowded Market Now Embrace Ebonex, The New China-Based Exchange Linked to an Embezzlement Scheme, Running a Singaporean Entity (With a Privacy Policy And Finance Service Agreement Referencing The Cayman Islands)?

Given that exchanges are being entrusted with users’ money, best execution, and security protecting against fraud and hackers, established companies with clean track records are the obvious go to for new users.

Leaders in the field like Coinbase, Kraken and Bitfinex were started in 2012, 2011 and 2012 respectively.

Other exchanges with established brands like Robinhood (which launched in 2018) make the environment even more challenging for an undifferentiated exchange.

Enter Ebang, which already has ties to a massive Chinese embezzlement scheme, multiple fraud allegations from customers, and extensive capital outflows to Cayman-based entities linked to its controversial underwriter. [13]

Of all the crypto exchanges, investors should ask themselves; is this really the exchange you feel most comfortable using and recommending to your friends? Would people rather use something like Coinbase, a US based company with a brand that’s been around for almost 10 years without major incident, or one of the other top brands?

Conclusion: A One-Way Street—The Cash Isn’t Coming Back

Given Ebang’s rocky track record in China and its sketchy underwriter, we think its IPO and secondary proceeds are gone.

We get it—investing in crypto can be fun. It’s volatile; it can be a rush. Will they press-release something to do with NFTs and send it to the moon? What is the next piece of the ‘story’?

But investors in Ebang should recognize that this is mainly a story, with not much of a business to support it. Ebang displays all the classic hallmarks of a capital-raising scheme. And while speculators all hope the next “news” will provide that little stock spike, experienced investors know the news looming shortly thereafter is likely to be the other kind— secondary share sales that allow management to cash out while sending the stock plunging.

In the end these things always take the rocky road down, dragging unsuspecting investors along for the ride. We don’t expect a dime of the money will come back, but we wish the best of luck to all.

Disclosure: We are short shares of Ebang International Holdings Inc. (NASDAQ:EBON)

Legal Disclaimer

Use of Hindenburg Research’s research is at your own risk. In no event should Hindenburg Research or any affiliated party be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information in this report. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities covered herein. You should assume that as of the publication date of any short-biased report or letter, Hindenburg Research (possibly along with or through our members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or consultants) along with our clients and/or investors has a short position in all stocks (and/or options of the stock) covered herein, and therefore stands to realize significant gains in the event that the price of any stock covered herein declines. Following publication of any report or letter, we intend to continue transacting in the securities covered herein, and we may be long, short, or neutral at any time hereafter regardless of our initial recommendation, conclusions, or opinions. This is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. Hindenburg Research is not registered as an investment advisor in the United States or have similar registration in any other jurisdiction. To the best of our ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the stock covered herein or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Hindenburg Research makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Hindenburg Research does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein.

[1] US$91.7 million in net proceeds from June 26, 2020 IPO, US$39.2 million from November 2020 offering, US$90 million from a February 2021 offering, and US$68 million from a Warrant Inducement Offering in February 2021, and $85.4 in gross proceeds from an April offering. Note that the number is likely to go up, as while the April offering is a gross figure, the company has a history of subsequently upsizing offerings post-announcement, as it intends to do here.

[2] Managed by Beijing Dongfang Caiyun Financial Information Services Co., Ltd 北京东方财蕴金融信息服务有限公司

[3] International Merchants Holdings (IMH) is a Cayman-registered entity formed in March 2017 with very little public presence. We found no public website for IMH and the only public references we found for the entity were in relation to several deals it had done with companies underwritten by AMTD, Ebang’s underwriter. (1,2,3,4) Our review of IMH shows that it has a convoluted relationship with Ebang’s IPO underwriter, AMTD. Beyond just participating in the underwriters deal’s as an investor, the entity has also participated in a series of complex transactions involving investments directly into AMTD.

[5] Notably, on the subject of auditors, Ebang’s auditor is MaloneBailey LLP. The audit firm handled more Chinese reverse merger clients in 2011 than any U.S.-based audit firm, according to a critical report issued by the Public Company Accounting Oversight Board (PCAOB) that focused on the wave of questionable Chinese listings. Subsequent PCAOB inspections have repeatedly shown MaloneBailey to have significant auditing deficiencies (2013, 2014, 2016, 2017):

“deficiencies identified were of such significance that it appeared to the inspection team that the Firm, at the time it issued its audit report, had not obtained sufficient appropriate audit evidence to support its opinion”

[6] It later upsized the offering to $39.2 million, and $68 million in warrant proceeds, per a later prospectus [Pg. 4]

[7] The IPO prospectus shows that Dong Hu’s relative was owed $24.1 million. [Pg. 141] A late-October prospectus shows that it was mostly repaid, leaving a balance of $3.1 million, representing a net paydown of $21 million. [Pg. 93] The prospectus amendments do not make clear exactly when the paydown occurred.

[8] The Ebang entity is Zhejiang Ebang Telcom Technology Co., Ltd (浙江亿邦通信科技有限公司) and the customer named is Beijing Mobcolor Technology Co., Ltd (北京新彩量科技有限公司)

[9] The “Letter to Apply for Delayed Payment” was drafted by Ebang. Beijing Mobcolor stated that Ebang, subsequently used an unnamed individual to transfer USD 1.5 million to Zou Taifeng (邹泰峰), who then transferred the money to Xiamen Yakexun Electronics Technology Co., Ltd (厦门亚克讯电子科技有限公司),which paid Beijing Mobcolor USD 1.5 million circa November 2018.

[10] Based on 125,209,554 Class A ordinary shares and 46,625,783 Class B ordinary shares [Pg,65] and a per share increase of $5.37.

[12] For example, Huobi, a crypto exchange with one fourth of Ebonex’s ETH/BTC pair volume reported at the time we checked has over 280 thousand Twitter followers.

[13] Ebonex’s website references its Singaporean entity yet for some reason also points to a Cayman entity of a similar name for its Privacy Policy and Finance Services Agreement. A Cayman entity search turned up no entity named Ebonex. The documents appear to be copied from rival exchange Huobi.