(NASDAQ:CLOV)

- Today, we reveal how Clover Health and its Wall Street celebrity promoter, Chamath Palihapitiya, misled investors about critical aspects of Clover’s business in the run-up to the company’s SPAC go-public transaction last month.

- Our investigation into Clover Health has spanned almost 4 months and has included more than a dozen interviews with former employees, competitors, and industry experts, dozens of calls to doctor’s offices, and a review of thousands of pages of government reports, insurance filings, regulatory filings, and company marketing materials.

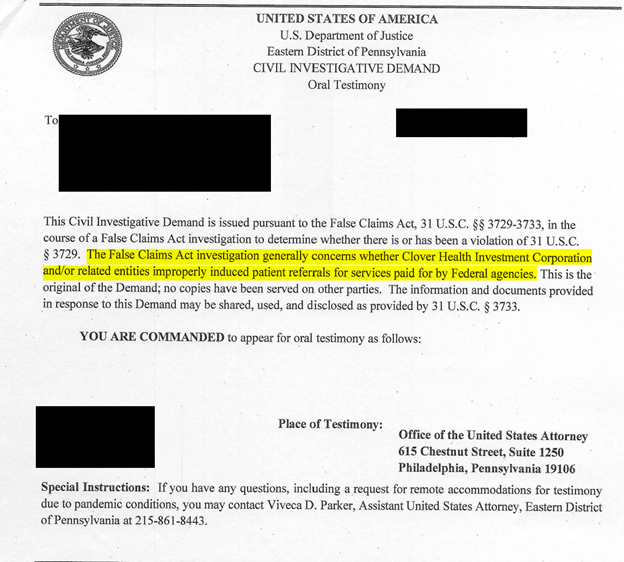

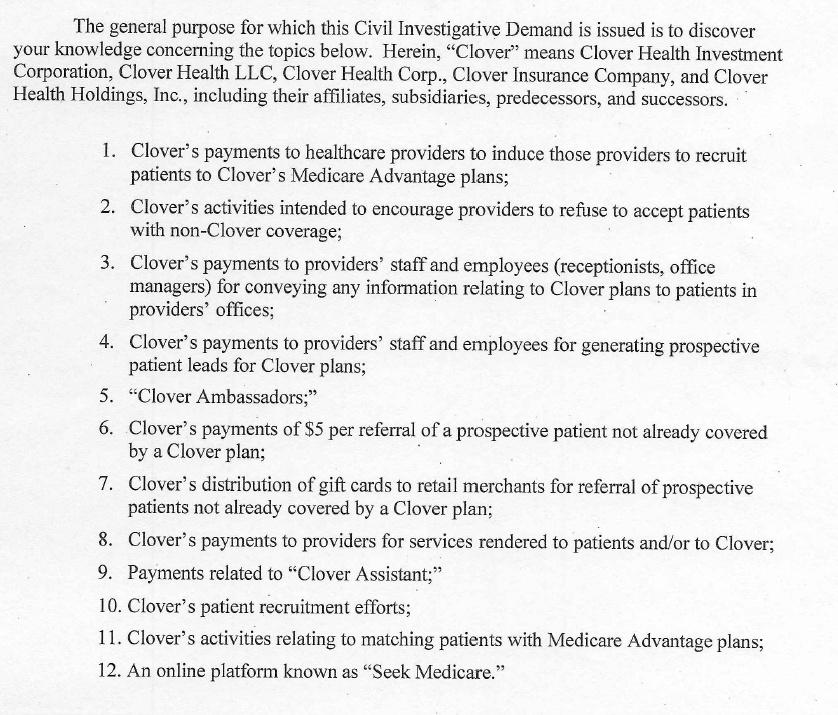

- Critically, Clover has not disclosed that its business model and its software offering, called the Clover Assistant, are under active investigation by the Department of Justice (DOJ), which is investigating at least 12 issues ranging from kickbacks to marketing practices to undisclosed third-party deals, according to a Civil Investigative Demand (similar to a subpoena) we obtained.

- This Civil Investigative Demand and the corresponding investigation present a potential existential risk for a company that derives almost all of its revenue from Medicare, a government payor. Our research indicates that the investigation has merit.

- Clover claims that its best-in-class technology fuels its sales growth. We found that much of Clover’s sales are driven by a major undisclosed related party deal and misleading marketing targeting the elderly.

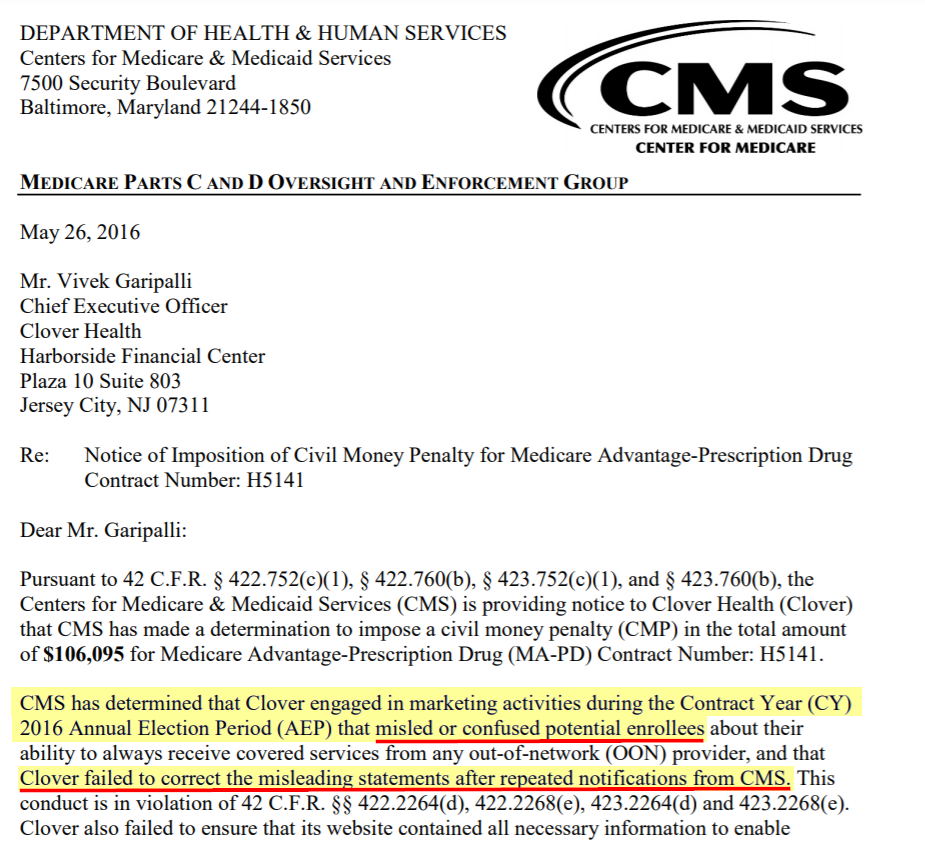

- These practices should not come as a surprise, given that in 2016, Clover was fined for misleading marketing practices by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS). The fine was issued after Clover’s repeated failure to amend misleading statements about its plan offerings. A former employee told us the fine was so small it just emboldened Clover to push the envelope further.

- Clover has a thinly-disclosed subsidiary called “Seek Insurance”. Seek makes no mention of its relationship with Clover on its website yet misleadingly advertises to seniors that it offers “independent” and “unbiased” advice on selecting Medicare plans. It claims, “We don’t work for insurance companies. We work for you”, despite literally being owned by Clover, an insurance company. Its activities are also under investigation by the DOJ.

- Multiple former employees explained that much of Clover’s sales are fueled by a major undisclosed relationship between Clover and an outside brokerage firm controlled by Clover’s Head of Sales, Hiram Bermudez. One former employee estimated Bermudez drove ~68% of Clover’s total sales, though was unclear on the amount coming from the undisclosed relationship.

- One of the former employees explained that Clover’s Head of Sales took efforts to conceal the relationship by putting it in his wife’s name “for compliance purposes”. Insurance filings confirm this. The Clover contract was quietly put into his wife’s name in the weeks after Clover’s go-public announcement.

- In a CNBC interview announcing the Clover transaction, Chamath proclaimed, unprompted, “they create transparency…they don’t motivate doctors to upcode or do all kinds of things to get paid”. A former employee explained to us that the DOJ is specifically asking about upcoding, or the practice of overbilling Medicare.

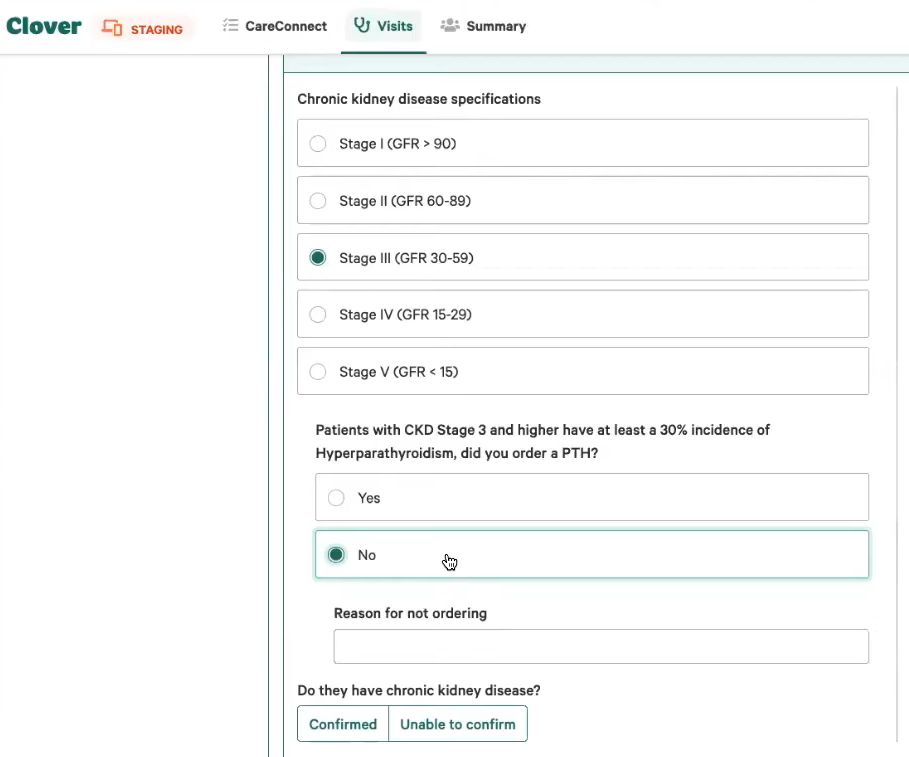

- Multiple former employees explained that Clover’s software is primarily a tool to help the company increase coding reimbursement. We provide detail on how the software captures and retains irrelevant diagnoses, which we believe deceives the healthcare system, and poses a significant regulatory risk.

- Clover claims its software “delights” physicians, but according to doctors and former employees we interviewed, they use it because Clover pays them extra to use it. Physicians are paid $200 per visit to use the software, twice the normal reimbursement rate for a Medicare visit.

- Doctors at key Clover providers described the software as “embarrassingly rudimentary”, “a waste of my time” and as just another administrative hassle to deal with.

- Clover’s CTO left 6 months before the first release of the supposed “disruptive” Clover Assistant software in July 2018 (likely a sign that development wasn’t going great.) Clover’s executive team has been in turmoil, with 3 CFOs, 3 COOs, and 2 General Counsels in the last 4 years.

- Prior to founding Clover, CEO Vivek Garipalli owned 3 New Jersey hospitals through a company called CarePoint Health. CarePoint was publicly lambasted for price-gouging; its hospital charged the highest prices for emergency room treatment in the entire country.

- For example, local media reported that Garipalli’s hospitals charged a teacher $9,000 for a bandaged finger and a tetanus shot, and another patient $17,000 for 5-6 stiches on a cut hand.

- In 2015, as it came under increasing regulatory scrutiny, Garipalli made a secret $1 million donation to the Jersey City Mayor through a shell entity. Garipalli was only revealed as the donor after a non-profit sued to expose the mystery backer.

- CarePoint’s predatory price-gouging was lucrative. But in 2020, New Jersey legislators accused Garipalli – now a public company CEO – of siphoning over $157 million from his hospital network through a byzantine web of LLC shell entities. The transactions left the hospitals financially crippled, leading to layoffs and a liquidating sale process to new owners.

- Meanwhile, Chamath has described Garipalli as “an absolute proven moneymaker”.

- That could be because Chamath’s firm received over 20 million “founders shares” (worth ~$290 million at current prices) in exchange for $25,000 and for promoting the Clover Health SPAC.

- Given that investors are paying over a quarter billion dollars for Chamath’s due diligence, we think they deserve to know whether Chamath knew of these issues and concealed them, or whether he simply failed to notice them at all.

- Short sellers have exposed almost every major market fraud in the past several decades, yet there have been recent questions about whether short-sellers and critical researchers play an important role in a healthy, functioning market. We hope our research today serves as a timely reminder that they do. For more on this, see our conclusion.

Initial Disclosure: This report represents our opinion, and we encourage every reader to do their own due diligence. Please see our full disclaimer at the bottom of the report. We have no position (short or long) in Clover Health because we think in this moment for public markets, it is more important for people to understand the role short sellers play in exposing fraud and corporate malfeasance. For more on that discussion, see our conclusion. For members of the media who wish to independently corroborate our work, please contact us for information on sources on condition that their anonymity is maintained unless they explicitly agree to go on-record.

Introduction

Clover “has been diligenced and validated not just by me and my team at Social Capital, but by some of the most respected blue chip technology investors in the world.”

– Chamath Palihapitiya, October 6, 2020, Investor Presentation

The market has seen an epic upheaval over the past several weeks, with average investors realizing their strength in an environment that has long been dominated by large institutions and corporate insiders.

At the center of this shift, a vocal figure has appeared: Social Capital founder Chamath Palihapitiya, who has taken interviews with everybody from CNBC to AOC, railing against the establishment elite and expressing his support for the rise of individual traders.

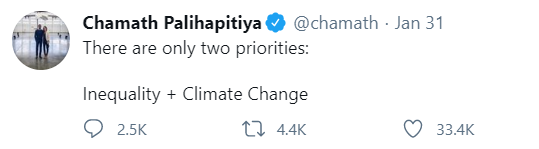

Chamath has expressed views we wholeheartedly agree with:

- Wall Street is a corrupt cesspool. This is why we have been shining light on it for almost half a decade.

- When things go south, bankers and executives cry for bailouts and regulation to stack the deck. This is wrong, and it shouldn’t happen.

- People should not be censored. We welcome the democratization of information and publishing. Hindenburg launched 4 years ago with a staff of one, flat broke, on the verge of eviction, and facing lawsuits from powerful corporations. We did it with nothing more than a website and a Twitter account dedicated to exposing fraud.

But while we agree with the ideals being supported by Chamath, we’re also skeptics by nature. And we were intrigued to see a billionaire taking media calls from his mansion, making hundreds of millions of dollars selling SPACs to retail investors, all while positioning himself as the de facto leader of the average Joe.

Coincidentally, we began looking at Clover Health well before the current market chaos. The name first crossed our radar in October 2020, when Chamath began a media tour explaining his reasoning for taking the company public via SPAC.

Since then, while Chamath has seemingly taken every opportunity available to present himself as a beacon of rigorous due diligence and Wall Street know-how, our 4-month investigation led us to conclude that Clover Health’s culture is rooted in deception and has taken every opportunity to push or break the rules to mislead its customers, investors, and Medicare.

Clover is Under Active Investigation by the Department of Justice, An Existential Risk That Has Not Been Disclosed to Investors

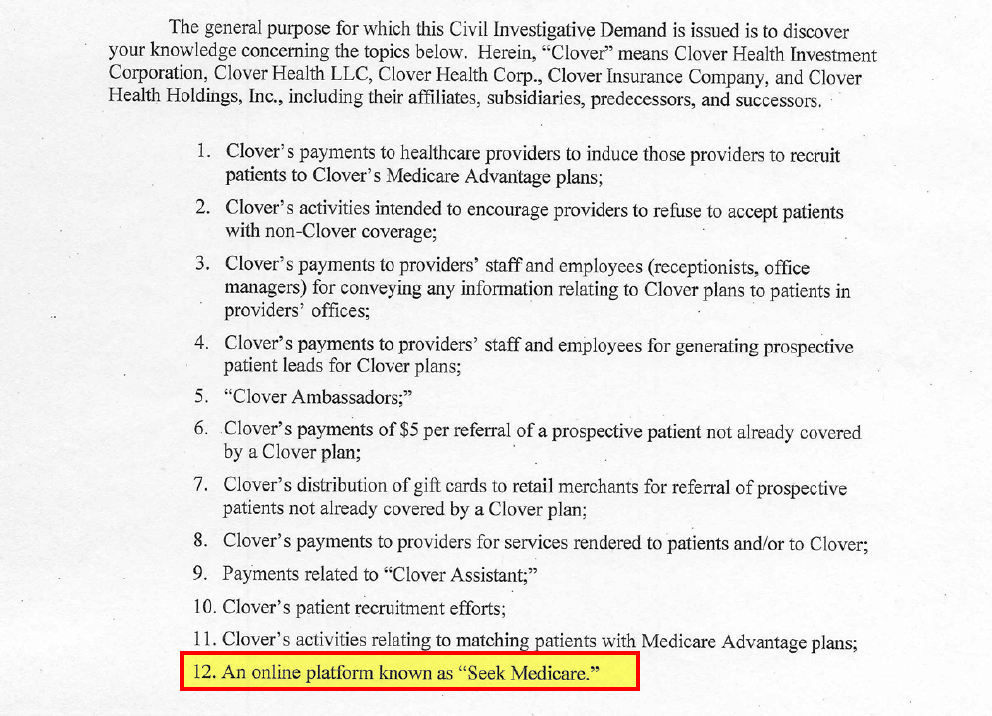

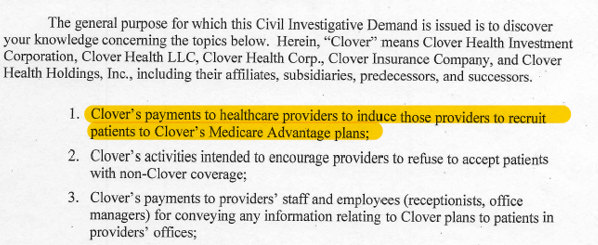

Key amongst our findings was discovering that Clover Health is under active investigation by the Department of Justice (DOJ). We obtained a copy of a DOJ Civil Investigative Demand (similar to a subpoena) sent to a former employee, which lists 12 specific areas of investigation.

The former employee told us they were issued a Civil Investigative Demand by the Eastern District of Pennsylvania in late October last year, just weeks after Chamath’s announcement to take Clover public, and months ahead of the ultimate go-public transaction.

This Civil Investigative Demand and the corresponding investigation have not been disclosed to investors, despite the existential risk a Department of Justice investigation poses for a company that derives almost all its revenue from Medicare, a government payor. [Pg. 46]

Chamath is positioned to benefit regardless of whether it works out for average investors. His firm invested $25,000 in exchange for an eventual 20,500,000 in “founders shares” for promoting Clover. [Pgs. 4-5] Those shares are valued at almost $290 million based on today’s stock price.

Chamath also invested $100 million at $10 per share through a related entity, putting his overall cost basis well below others.[1] [Pg. 6, Pg. 8]

We urge Chamath to answer the following questions:

- Did you know about the active DOJ investigation and about the underlying issues being investigated when you took the company public? If yes, why wasn’t it clearly disclosed?

- If you didn’t know, why are investors paying $290 million when your one job is due-diligence?

We think Chamath has done a masterful job marketing himself, capitalizing on the recent chaos with GameStop and WallStreetBets to align himself with “everyday” investors – but his public persona strikes us as the sugar that helps the poison go down.

Background: Basics on the Business And Clover’s Pitch to Investors

Clover Health was founded in New Jersey in 2012, then began selling Medicare Advantage in the state starting in 2013. [Pg. 273] The company has around 57,000 members, with about 98% of its revenue coming from New Jersey as of 2019. Over half of its plans are sold to low-income or minority seniors. [Pgs. 47, 38] The company is one of the fastest growing Medicare Advantage insurers in the nation. [Pg. 10]

Clover’s board members include former first daughter Chelsea Clinton, while its investors, including Sequoia and Alphabet’s GV, are a who’s who of venture capital elite.

Chamath announced on October 6th 2020 that he would be taking the company public, describing Clover as “the holy grail of what healthcare should do” and proclaiming that his team, along with some of the most respected investors in the world, have validated the company.

Clover’s proprietary software product, Clover Assistant, is the key that Chamath and Clover management have encouraged investors to bet on. The company claims its disruptive software creates “a virtuous cycle” of happier, better-informed doctors, healthier patients, and ultimately huge winnings for Clover and its investors. [Pg. 9]

Clover has generated consistent losses to date. As of September 30, 2020, the company had an accumulated deficit of ($901.6) million. [Pg. 39]

During the first nine months of 2020, Clover generated an operating loss of $25 million on revenue of $501 million, compared with an operating loss of $123 million on $344 million in revenue for the same period in 2019. [Pg. 29] The company has attributed the improvement partially to reduced medical expenses for members in 2020 as COVID-19 caused many to defer routine medical treatment. [Pg. 3] Clover hopes to become profitable in 2023.

Part I: Deceptive Sales Practices

Chamath: Best-In-Class Technology Is Why Clover “Consistently and Repeatedly Grabs 50% of Every New Available Member Every Year”

Our Research: Much of Clover’s Sales Seem to be Fueled by Misleading Marketing To The Elderly And A Major Undisclosed Related Party Deal With Clover’s Head of Sales

Some of These Arrangements Are Already the Subject of a DOJ Investigation

The very first page of Clover’s prospectus lays out all the reasons why its software product, Clover Assistant, results in “strong, industry-leading organic membership growth”. [Pg. 1-2]

During the October 6, 2020, investor call to promote the merger of Clover with his SPAC, Chamath reinforced that Clover’s technology is what is driving membership growth:

“Just like many other best-in-class software and technology companies, what you see here is a characteristic that we call land and expand, or negative churn. It’s a business that when it is in market consistently and repeatedly grabs 50% of every new available member every year. So the business very predictably can compound 25% to 30% for many years.” [Pg. 3]

Based on conversations with former employees and a review of corporate and insurance filings, we found that Clover’s membership growth looks to be driven not by technology, but rather by deceptive sales practices, including:

- A wholly owned Clover subsidiary that misleadingly markets itself as providing “independent” and “unbiased” advice to seniors looking for Medicare; and

- Large, undisclosed related-party transactions with a brokerage entity controlled by Clover’s Head of Sales.

As one former employee told us:

“The technology wasn’t any different. The plan design really wasn’t any different aside from it undercut the competition. But the first couple of years in network, it wasn’t even that great. They didn’t have all the hospitals in network. So, it had to have come from the sales strategy for their success to have grown organically the way it did.”

Not surprisingly, the DOJ subpoena lists numerous issues related to Clover’s member recruitment practices.

As noted above, this has not been disclosed to investors. The company’s prospectus includes an eye-glazing disclaimer suggesting that it is and could be under investigation by just about anyone at any given time without providing specifics:

“From time to time, we are and may be subject to regular and special governmental market conduct and other audits, investigations and reviews by, and we receive and may receive subpoenas and other requests for information from, various federal and state agencies, regulatory authorities, attorneys general, committees, subcommittees and members of the U.S. Congress and other state, federal and international governmental authorities.” [Pg. 57]

In 2016, Clover Was Fined For Misleading Marketing Practices by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS)

The DOJ investigation is not the first-time the government has investigated Clover. Several years after its 2013 launch, Clover was fined $106,095 by CMS for misleading marketing practices.

Specifically, Clover was alleged to have falsely led seniors to believe that Clover covered certain services that it didn’t. This would result in denial of service or out-of-pocket expenses for services the seniors thought were included.

CMS issued the fine after repeatedly warning Clover and after Clover’s failure to amend its misleading statements, according to the CMS release:

Former Employees: The $106,095 Fine Was So Small That it Just Emboldened CEO Garipalli To Keep Pushing the Envelope

According to a former employee we interviewed, the small size of the fine simply emboldened Clover CEO Vivek Garipalli:

“The problem was, when I got there the thought process was ‘well the penalty was so small we’re not worried about it.’…To me any penalty from the government or CMS is like a huge no no because you’re on their radar. And the one thing you never want to be with healthcare is on the CMS radar because that’s the number one payor in the country. No one pays more than CMS, so don’t bite the hand that feeds and put yourself in bad spot like that could get you banned from that marketplace quickly.”

Our research indicates that Clover has pushed the envelope.

Clover Has a Thinly Disclosed Subsidiary Called Seek Insurance Services, Inc.

Seek Makes No Mention of Clover on Its Website Yet Misleadingly Advertises to Seniors That it Offers “Independent” and “Unbiased” Information to Help Them Select Medicare Plans.

It appears that misleading marketing practices continue to this day.

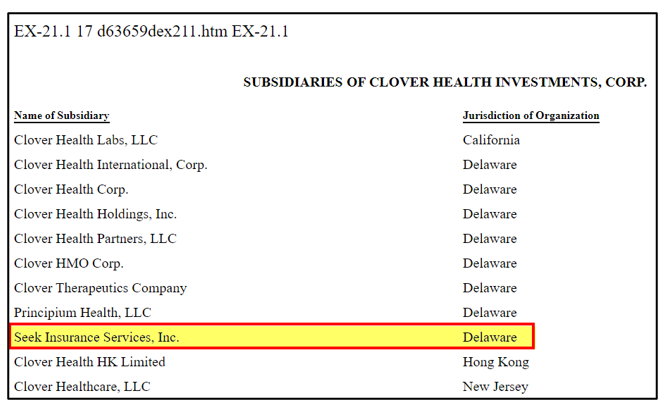

Seek Insurance Services, Inc. is a subsidiary of Clover, per Clover’s SEC filing exhibit listing its subsidiaries.

And Seek Insurance Services, Inc. is listed as the owner and operator of a website called SeekMedicare.com, which advises seniors on which Medicare insurance plans to choose.

Given that the stated purpose of Seek’s website is to help seniors pick Medicare insurance plans, we would expect it to disclose that it is actually owned by insurance company Clover, posing a major conflict of interest.

Yet Clover wasn’t mentioned anywhere on Seek’s website, per our review. On the contrary, Seek misleads its elderly audience by saying the exact opposite.

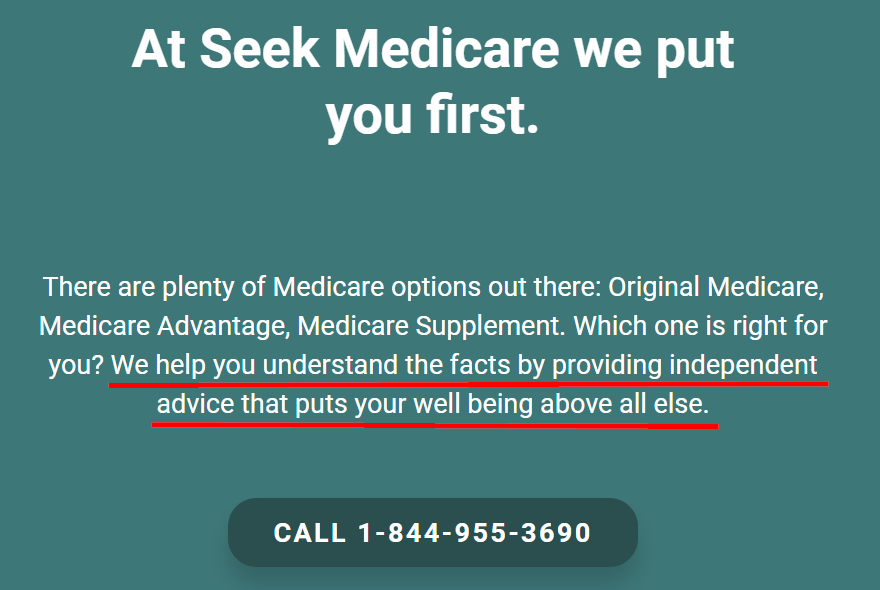

On one part of its website, superimposed over an image of a senior citizen, Seek explains how it offers totally unbiased advice:

Seek further markets itself as providing “independent advice that puts your well-being above all else”.

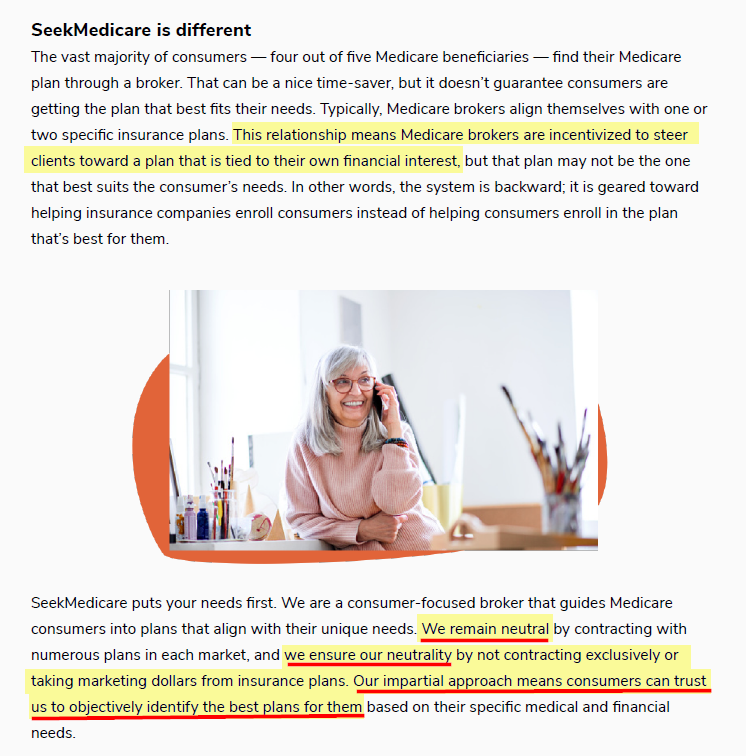

Seek also insists that it doesn’t care which insurance company plan seniors end up picking:

Seek’s website even has a blog post explaining how other brokers often have a bias to steer clients toward a plan that best serves their own financial interests. The post is titled “SeekMedicare is different” and repeatedly declares Seek’s neutrality:

Seek Medicare Website: “We Don’t Work for Insurance Companies. We Work For You”

Reality: Seek Is Literally Owned By Clover Health, An Insurance Company

On one part of Seek’s website, it explicitly claims that it doesn’t work for an insurance company at all:

(Note: Seek Insurance works for, and is literally owned by, insurance company Clover Health)

Seek’s website doesn’t list its executive team. But in case there is any doubt that Seek is an extension of Clover’s sales operation, Florida corporate records show that Seek’s Chief Sales Officer is Hiram Bermudez, who concurrently serves as Clover’s Head of Sales, per his LinkedIn profile.

Seek’s website doesn’t list an address, but New Jersey corporate documents show its address matches Clover’s New Jersey office address: 30 Montgomery Street, Jersey City, NJ, 15th Floor.

Seek’s Activities with Clover Are Under Investigation by the DOJ

Given the above, we were not surprised to see Clover’s relationship with Seek turn up on the Department of Justice CID which specifically requested information relating to “An online platform known as ‘Seek Medicare’.”

It is important that seniors be aware of marketing conflicts because not all Medicare Advantage plans are created equal. CMS assigns plans star ratings of 1 – 5, with a higher number of stars indicating a higher quality of care and customer service.

According to CMS, 81% of Medicare Advantage patients were enrolled in a plan that would have a 4-star rating or above by 2020.

Using CMS’s online tool for comparing Medicare Advantage plans, we reviewed plans available in Hoboken, NJ, and were shown 35 options, including several Clover Health plans. All of Clover’s plans had 3-star ratings, making them the lowest rated plans available in that region.

We think Clover is misleading seniors to steer them toward plans where it has an obvious conflict of interest, without disclosing that conflict.

Clover: Our Sales Are Fueled By Great Software

Former Employee: Clover’s Sales Are Fueled By An Undisclosed Relationship Between Clover And An Outside Insurance Brokerage Firm Controlled by Clover’s Head of Sales

The lack of disclosure goes beyond Clover’s “Seek” subsidiary. As mentioned above, Clover’s Head of Sales is an individual named Hiram Bermudez, per his LinkedIn profile.

Several former employees, a local competitor, and an independent broker told us that Bermudez oversaw the company’s aggressive expansion across New Jersey. One former employee estimated that Bermudez was responsible for at least 70% of the sales in the state, representing ~68% of Clover’s total sales.

Bermudez’s LinkedIn profile shows that prior to joining Clover in 2012, he worked at brokerage firm B&H Assurance, where he held the title of VP of Sales Operations. The profile indicates he left the role in 2012 upon joining Clover.

The most recent New Jersey corporate records, dated November 20th, 2020, indicate that Bermudez is not only still active with B&H, but is listed as the sole agent of the firm, as well as one of two principals.

B&H, which stands for Bermudez & Henson, operates what is known as a Field Marketing Organization, or an “FMO”. FMOs act as a middleman between insurance companies and brokers, negotiating sales deals with the insurance companies that a network of agents can then offer and sell to customers.

As one former employee explained, Bermudez never left B&H, and instead was brought on specifically to use his brokerage business to grow Clover’s sales.

“He was brought into Clover since early on, like day one, and because he had such a large ground force of sales agents he was key and instrumental in getting Clover started.”

“He’s got both feet in those waters; one is he’s head of sales at Clover and the other one is he owns and manages this massive sales market foundation in the Northeast under his FMO.”

A review of the B&H website shows that it is partners with Clover, yet we see zero disclosure that its key principal holds a concurrent senior role at the insurance company. One might expect this to be the type of conflict of interest that seniors purchasing Medicare would be interested to know.

Bermudez represents in his LinkedIn profile that his responsibilities at Clover include negotiating “aggressive contracts with FMO’s”. Given that Bermudez is a principal at a key FMO used by Clover, how aggressive can these negotiations be? Does he play hardball with himself?

Generally, companies are required to report related-party transactions to make prospective investors aware of material conflicts of interest.

Despite B&H clearly doing business with Clover, we saw no mention of the apparently significant related-party transactions in Clover’s SEC filings, including in its go-public prospectus.

Former Employee: Clover’s Head of Sales, Hiram Bermudez, Took Steps to Conceal the Relationship Between Clover and His Outside Brokerage Firm

“He Had to Get His Name Off of It…His Wife is Listed As a Co-Partner” “He’d Removed His Name on It For ‘Compliance Reasons’”

When we spoke to a former employee about B&H’s relationship with Clover, we were told that Bermudez had taken steps to conceal the relationship in the run-up to the go-public transaction due to “compliance reasons”:

“He just had to hand his business over to a partner, then he’d removed his name on it for compliance reasons.”

“His wife is listed as the co-partner with his business partner. He had to get his name off of it, but you know like there’s gonna be a check from Clover going to that business every year. It’s gonna be a large amount—he makes good money at Clover. He makes the majority of money from the sales that his business makes from Clover.”

We reviewed records from the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (“NAIC”). On the NAIC page for B&H Assurance, the entity listed its formal relationships (i.e., appointments) with most major insurance companies in New Jersey, 17 in all.

Clover was noticeably absent from the list (despite clearly appearing as a partner on the B&H website, as shown above.)

Digging one layer deeper, the NAIC records show that B&H listed a single affiliate relationship, with a woman named Yesenia Rivera.

According to a background check report, Yesenia Rivera is the maiden name of a woman who typically goes by Yesenia Bermudez—Hiram Bermudez’s wife.

Insurance Filings Confirm Clover’s Contract With The Brokerage Firm Was Quietly Moved Into Bermudez’s Wife’s Name In the Weeks After the Go-Public Announcement

On Bermudez’s wife’s NAIC profile, we see that she has a formal relationship with only one insurance company: Clover Health.

In short, Clover’s Head of Sales appears to operate a large, separate insurance brokerage firm that does significant undisclosed business with Clover, through his wife’s name. Clover then claims in the very first pages of its go-public prospectus to be generating its business organically due to its amazing software. [Pg. 1-2]

Per an interview with a former employee that described the relationship with Bermudez’s FMO:

“You don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to figure it out.”

An employee at a major competitor, who has experience with both Bermudez and the New Jersey market, opined that Bermudez is “one step away from going to prison, and that’s the way they run their business.”

Clover Handed Out Gift Cards to Doctors and Nurses to Generate Patient Leads, a Practice Prohibited by CMS, According to a Former Employee

In addition to soliciting potential members through brokers and websites with undisclosed conflicts, Clover also skirted regulations by recruiting members through physicians’ practices, according to a former employee.

Clover distributed gift cards “all over the freaking map” to encourage providers to direct their patients toward Clover’s plans, the former employee said. “Dunkin Donuts, Panera, Amazon.”

Gift cards were used because they were untraceable, the former employee added.

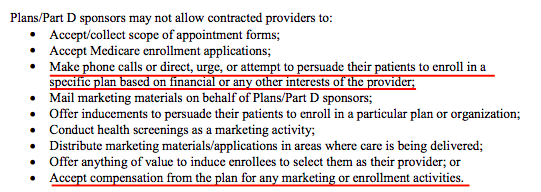

Such payments would appear to violate CMS’s rules regarding marketing of Medicare Advantage plans. These rules place restrictions on providers recruiting members into an insurer’s plan based on financial or any other interests of the provider: [Pg. 15]

The official explanation for these gift cards was everything except recruitment, according to the former employee. The gifts were justified as being for “morale,” a “thank you,” “motivation,” and “friendship.”

This issue is cited specifically in the DOJ subpoena as well:

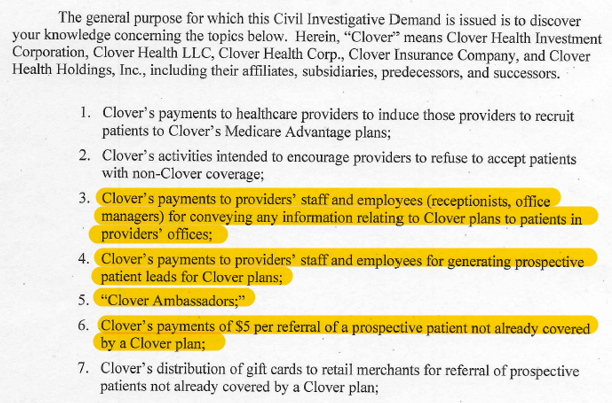

Clover Paid Staff in Physician’s Offices, Known as Clover Ambassadors, For Referrals to Promote Clover’s Plans to Seniors.

“It’s a Confidential Program,” a Former Employee Explained, and One That is Being Looked at by the DOJ (Once Again Unbeknownst to Investors)

Clover also paid physicians’ front desk staff for patient referrals, according to a former employee.

These individuals were referred to as “Clover Ambassadors,” according to the former employee, who added: “It’s a confidential program,” meaning ambassadors weren’t supposed to let patients know they were working for Clover.

“The receptionist would notice that a patient checking in was enrolled in, say, United Healthcare, and would mention to the patient that there was another plan that might meet their needs better – ‘Do you want more information? No problem. I’ll have them give you a call.’”

The government is looking into these activities as well:

Part II: Undisclosed Overbilling Risk (“Upcoding”)

Clover operates as a Medicare Advantage insurer, deriving almost all its revenue from the government. [Pg. 46, Pg. 9]

Unlike traditional Medicare, which operates a “pay for service” model, Medicare Advantage pays insurers a per-member-per-month rate in order to manage each member’s care. Then, the insurer participates in some of the gains or the losses associated with the cost of care. The goal of the program is to incentivize insurers to proactively find ways to lower the cost of care.

The Medicare Advantage program has a key nuance that opens the door for fraud. CMS recognizes that sicker patients are likely to cost more to insure, so CMS increases its payments to insurers if a patient’s “risk assessment” score is higher. Given this dynamic, it is in the insurer’s best interest to make its patients look as sick as possible, thereby earning higher reimbursement.

Insurers can game the system by inflating diagnoses or failing to remove old, irrelevant diagnoses. This is commonly considered “risk adjustment fraud”, a form of upcoding.

Based on our research, Clover and its software product seem specifically designed in a way that exposes the company to this very risk.

Chamath On CNBC Prior To Going Public: “They Create Transparency…They Don’t Motivate Doctors to Upcode or Do All Kinds of Things In Order to Get Paid”

Former Employee: Clover is Under Investigation by the Department of Justice Over Upcoding

A government investigation into upcoding can be an existential issue for companies that are reliant on government payor programs like Medicare.

Given that almost all of Clover’s revenue is derived from Medicare Advantage premiums, investors might rightfully be worried that the risks associated with such an investigation could threaten its relationship with the government. [Pg. 46]

Prospective investors in Clover, however, were comforted by Chamath, the head of Clover’s SPAC sponsor, in a CNBC interview in October 2020 with Andrew Ross Sorkin, during the run-up to Clover’s go-public transaction.

In the interview, Chamath offered (unprompted) that Clover wasn’t engaged in the untoward practice of “upcoding”, or inputting inaccurate medical information to increase reimbursement from government payors such as Medicare:

“They create transparency. They don’t play games. They don’t motivate doctors to upcode or do all kinds of things in order to get paid.”

– Chamath Palihapitiya (1:07-mark)

But upcoding happens to be a key issue that has drawn the attention of the Department of Justice, according to a former employee we interviewed, who provided a copy of the Civil Investigative Demand.

The former employee said they were questioned about “this tool (Clover Assistant) and its practice of promoting higher level coding by the physician so that way the insurance can bill CMS.”

Clover: The Clover Assistant is Primarily a Tool to Improve Patient Care

Multiple Former Employees: Clover’s Software is Primarily a Tool to Help the Company Increase Coding Reimbursement

Our research indicates once again that the DOJ probe is likely onto something.

While Clover claims its software tool, Clover Assistant, is aimed at helping doctors improve patient care, former employees told us that it was first and foremost a coding tool. According to one former employee:

“The core feature of the platform is it increases revenue by identifying chronic conditions that people have and CMS will pay that…That’s the core business proposition.”

They further explained how it works:

“What it’s doing is saying we have your claims and in your claims at some point some doctor diagnosed your hypertension. The doctor that’s sitting in front of you right now, we want them to say that you have hypertension. The doctor can say ‘yes’ or ‘no’ based on their findings. But it’s a sort of a nudge to the doctor to identify these potential chronic conditions you have.”

Per another former employee we interviewed:

“If you make this patient look really, really sick, you are going to get more money from the government…I think the government may say it’s not bad if a patient really is that sick. It gets dicey when you have a program that you are paying doctors straight up crazy amount of money to log in to and do this for you.”

As we will detail later, Clover pays providers $200 per visit to use the Clover Assistant. One former employee explained how the payment is essentially an investment for Clover, given the potential to increase diagnosis codes and earn higher reimbursement:

“If you are paying doctors $200 for a click but you are able to increase the severity of patients that you’ve diagnosed, it’s worth it because you are drawing down thousands of dollars (from Medicare) for a couple of clicks. To me that’s why they have this.”

Does Clover Encourage Upcoding? The Clover Assistant “Recaptures” Old, Often Irrelevant Diagnoses, Then Makes it Difficult to Remove Them, According to Doctors

Clover’s drive to capture every possible diagnosis has, predictably, led to messy results.

Note that capturing relevant prior diagnoses is a perfectly acceptable practice. But according to doctors we interviewed, Clover Assistant retains old and often irrelevant diagnoses, ultimately leading to wasted Medicare dollars.

Per one doctor who works at a NJ practices that has dozens of doctors using the Clover Assistant:

“[Clover] is like constantly throwing those codes back in our face for everything that’s ever come up when they are irrelevant now.”

The doctor distinguished Clover from Athena, the electronic medical record (EMR) system used by the practice for its patients, which also prompts doctors to consider confirming diagnoses based on information gathered on the patient. The doctor described Clover as being much less precise:

“They have all these ridiculous diagnoses in there that make no sense…Every single time I go in more than half the diagnosis aren’t right…Whereas with Athena, I would say you know 4%-5% of the time the diagnosis aren’t right.”

Another doctor estimated that Clover Assistant’s patient records were inaccurate between 10% and 25% of the time, adding:

“Let’s say somebody came in with diabetes. They lost a bunch of weight. They exercise. They don’t have diabetes anymore. That diabetes is still on the record.”

We asked why some of these cleared up/cured legacy issues continue to show up as diagnosis. The doctors explained that the software limits their ability to remove an inapplicable diagnosis and expressed some confusion why such an obvious feature hadn’t already been implemented:

One doctor told us:

“Your patients don’t necessarily fit into one of their boxes, but you have to click a box to get to the next screen.”

The doctor added:

“I can’t click past the screen. But maybe this (diagnosis) is no longer applicable for this patient… If there was just a spot to say this is no longer applicable, then I think the software would be improved instantaneously. And it is an easy thing.”

Another doctor we spoke with described how the Clover Assistant did not allow her to remove a current COVID diagnosis for a patient who had recovered from the virus but was taking a long-term course of medication to prevent blood clots, which the patient had experienced when ill with COVID. The system had been incapable of specifying the difference between a previous and current diagnosis.

“The menus are so unspecific that from what I checked, they could think that he currently has active COVID which he doesn’t have.”

It is unclear whether the difficulty doctors were having with removing old irrelevant diagnoses was part of a strategy to increase risk assessment scores, clunky development, or both. From the perspective of CMS, the distinction may not matter. Illegitimate increases in a patient’s risk score can lead to penalties and regulatory sanctions. [Pg. 37]

Clover’s CEO’s Prior Business Entered into a ~$1,000,000 Settlement With New Jersey’s Medicaid Fraud Division Following an Investigation Into Upcoding

This isn’t the first time Clover’s leadership has been in the spotlight over upcoding.

Prior to founding Clover, CEO Vivek Garipalli operated a series of New Jersey Hospitals under a business called CarePoint.

In February 2019, CarePoint disclosed to the New Jersey Medicaid Fraud Division 3 categories of billing claims that apparently lacked sufficient documentation, from claims made between 2015 and 2017.

CarePoint then settled with the regulator, agreeing to pay almost $1 million, representing the total of the overpayments from Medicaid. [1, 2] (In Part IV we go into extensive detail on CarePoint and its history of regulatory issues.)

Part III: Clover’s Software—A Hollow Pretense For a ‘Unicorn’ Multiple

Clover Claims Its Software “Delights” Physicians

Reality: Clover Has to Pay Doctors $200 Per Visit to Use the Software

Clover claims it operates a “software centered strategy”, driven by its Clover Assistant. Its prospectus declares that “physicians love the Clover Assistant”, “the Clover Assistant is a physicians ‘best friend’” and that it “delights” them. [Pgs. 236-237]

Often, software that delights customers is sold to them, resulting in revenue for the software company. In other instances, such as with companies like Google and Facebook, the aim is to provide delightful software for free in the hopes of rapidly growing user adoption, which then forms a foundation to generate revenue.

Contrary to these market-tested approaches, Clover instead pays doctors $200 per visit to use its software, resulting in Clover paying twice the average Medicare reimbursement rate for a standard visit. [Pg. 57, Pg. 252]

A former Clover employee we spoke with threw cold water on the idea that Clover’s software was useful, but suggested that doctors were delighted to get paid twice as much as usual:

“The doctors aren’t amazed by the software… They like the fact they are getting paid extra. You have to pay them to do more clicks. You have to pay them to add clicks to their daily routine.”

“Healthcare is so full of clinical decision support tools and so full of tech. The doctors are not being helped that much.”

One competitor expressed their blunt opinion on Clover’s software:

“It’s a really interesting concept that they have. They have this vaporware that doesn’t exist, right? They have 15, 20 programmers in an office in San Francisco. United Healthcare has 20,000 all over the Philippines and India. And there is no secret sauce, but somehow Clover and their 20 programmers have figured out the secret sauce.”

The competitor had previously met with Clover’s Head of Sales, Hiram Bermudez, and shared a story:

“…I remember being in a meeting with Hiram and he’s telling me about their technology. I said, ‘Hiram I was in the IT business for years. What are you talking about? You have nothing. And he starts laughing, right? He said, ‘Yeah, but it’s a great story, right?’”

Former Employees and Doctors Told Us The Software Is Burdensome and Basic

One Doctor Called Clover Assistant “Embarrassingly Rudimentary”

We spoke with former employees and doctors who use the software in order to get their views.

The software is a relatively quick “check the box” type application which is hardly compatible with creating an effective treatment plan, one former employee explained.

The number one issue doctors complained about with Clover Assistant was its inability to connect with physicians’ Electric Medical Record (EMR) systems, a former employee told us:

“Most of their time went into building Clover Assistant and not into bridging it into EMR systems…Management talked about integrating the Clover Assistant with EMR systems, but it was years away”.

One of the company’s former senior employees, whom we interviewed, dismissed the idea that Clover would ever make a meaningful effort to integrate with existing EMR systems:

“EMR integrations are a total joke. That’s not even possible or even something we’d want to do because of the functionality once you get in there. They (physicians) don’t even use it anyways to drive their visits most of the time.”

A practice with multiple Clover Preferred doctors in New Jersey told us that this lack of integration meant providers had to run through two software programs with every Clover patient.

“For patients that have this specific insurance, Clover Health, there’s an additional piece of software that Clover Health presents the office and asks us to register with so that when we see their patients that have Clover Health insurance, we do this extra step of work with their software, the Clover Health assistant.”

When asked why they do the extra work, they said candidly:

“The reason why we’re doing this extra work is because they present it as an additional billing opportunity for the office.”

While the system offered some recommendations regarding patient care and prompts regarding previous diagnoses, these are not unique features, according to the doctor, who said their practice uses Athena as its EMR, which also prompts doctors to consider past diagnoses.

Another doctor told us that preventative care-style medical records have been around for years with software like eClinicalWorks.

Another doctor we interviewed at a large New Jersey practice that uses Clover Assistant told us doctors were frustrated with the software but were obligated to use it to generate additional revenue for the practice.

Clover touts how the software was “developed by physicians for physicians”, but the doctor called the Clover Assistant “an embarrassingly rudimentary electronic medical record” and said the question prompts appear to have been written by someone with no medical background. [Pg. 238]

And a former senior employee, who spoke to us, went further saying Clover Assistant was never envisaged primarily for use by the physician:

“The tool is really made for the medical assistant doing most of the documentation and the doctor is basically just signing off on it.”

Clover Claims It Has Built A “Broad Base of Engaged Physicians” Who Use The Clover Assistant For 92% Of Their Visits

Reality: The Majority of Doctors in Clover’s Network Don’t Use the Clover Assistant, We Were Told

Clover tells investors it has “built a broad base of engaged physicians” and that “onboarded PCPs (primary care physicians) used the CA (Clover Assistant) for 92% of eligible visits in 2019.” [Pg. 14]

This 92% figure appears to be a clever turn of phrase. Clover never defines “onboarded” in its prospectus. [Pg. 247] In the field, Clover designates some doctors as “Clover Preferred”, or “a primary care physician who has been recognized for their dedication to using the Clover Assistant tool.” Two former employees explained that only “Clover Preferred” doctors were using the Clover Assistant.

But the proportion of “Clover Preferred” doctors is quite low. For example, according to Clover’s own database, only ~45% of all in-network doctors in a key New Jersey market, Passaic County, are defined as “Clover Preferred”.

In another key market, Morris County, New Jersey, only ~25% of all in-network doctors are “Clover Preferred” providers.

A former employee explained that Clover was able to enroll about 70% to 80% of all the primary care doctors in New Jersey into its network, but that didn’t translate into a high percentage of Clover Assistant users:

“They had a good portion of doctors in the state but not a great portion of doctors were using it if they enrolled.”

The acceptance rate drops dramatically outside of New Jersey, according to our review of Clover’s database.

- In El Paso, Texas, for example, the Clover directory lists 110 doctors in Clover’s network and only 8 that are identified as Clover Preferred doctors.

- For Tennessee, we found 220 primary care doctors in Clover’s network but none who identified as Clover Preferred providers.

- Arizona has 206 in-network providers but we found no Clover Preferred doctors.

It seems Clover is using claims about a small subset of its network, “onboarded PCPs,” to give the impression of widespread acceptance of the Clover Assistant.

We emailed the company asking for clarification on this “onboarded” metric and have not heard back as of this writing.

We Reached Out to Doctors Identified By Clover For Their “Dedication” to The Clover Assistant

They Indicated Erratic Use and Frustration; “Sick And Tired Of Yet Another Website”, “Ridiculous Diagnoses”, “Not Something That Helps Doctors Take Care of Patients”

In mid-January 2021, we phoned 22 physician’s practices, of various specialties and disciplines, in various parts of New Jersey listed in Clover’s 2019 Provider Directory to inquire whether or not they used Clover’s software.

Given that Clover claims its software has disrupted the healthcare market, we figured the practices would be able to provide their feedback on the revolutionary shift.

While all offices confirmed to us that they accepted Clover’s insurance, 14 offices (64%) told us they did not use the software in office, 4 told us they didn’t know whether or not they used the software and only 4 confirmed they did use the software.

We also spoke with two doctors at the Summit Medical Group, which appears to be the largest Clover Preferred provider in the company’s network. (Out of approximately 900 doctors using the Clover Assistant in northern New Jersey, the company’s largest market, 100 work at Summit Medical Group, according to our review of the company’s directory.)

Both doctors expressed frustration with the Clover Assistant. The first doctor bluntly labeled Clover “a waste of time”, adding:

“I know that all the doctors in my office, basically, they just feel annoyed by it. We just try to check it and get it closed as quickly as possible so that we get paid and move on to actual patient care.”

The second doctor responded when asked about the Clover Assistant:

“Sick and tired of yet another website, another log in, another system we are responsible for updating for some big data; another care consideration to respond to. We no longer have time to take care of our patients. Someone thinks this system will – what? It is not something that helps family doctors take care of their patients.”

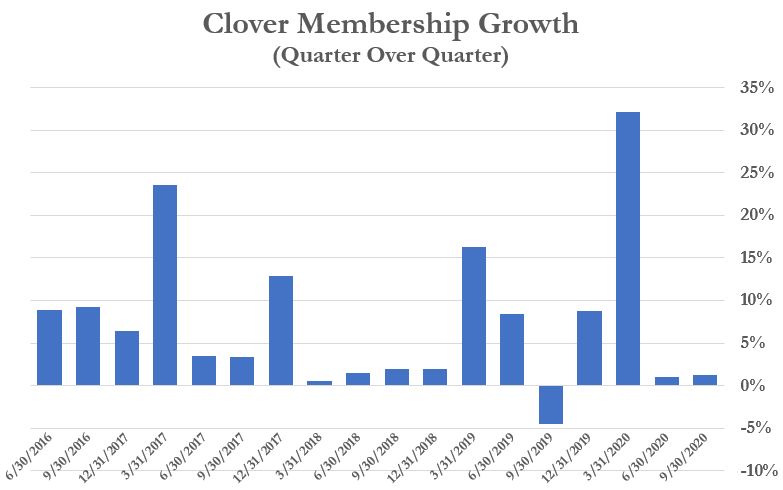

Clover Has Seen Its Membership Grow, But In Sporadic Fashion: Hardly Evidence of Rapid Software Adoption

Note that the company only launched its first software product 2.5 years ago, in July 2018. [Pg. 247]

Historical data shows that Clover’s membership has grown, but its quarterly growth rate has been lumpy and sporadic since its software release – hardly indicative of the consistent “hockey-stick” growth hoped for by software-driven companies.

Clover’s Chief Technology Officer Left 6 Months Before the First Release of Clover’s Software Product, Likely Not a Sign That Things Were Going Great

Clover Has Experienced Other Significant Executive Turnover: 3 CFOs, 3 COOs, and 2 General Counsels Over the Last 4 Years

Typically, when a company is on the cusp of releasing a groundbreaking piece of software that will change the world, the Chief Technology Officer will stick around to reap the fruits of their labor.

But Kris Gale, who was Clover’s original CTO from Jul. 2014 – Jan. 2018, left the position just 6 months before the release of Clover Assistant. Gale later served as an advisor until February 2019, per his LinkedIn. Currently, Andrew Toy serves in the CTO role.

In general, executive stability can be a sign of a healthy organization. At Clover, we have seen extensive executive turnover in the company’s brief history.

CFO Turnover: 3 CFOs over the last 3 years

- Les Granow – Jul. 2016 to Mar. 2018

- Pritam Baxi – Mar. 2018 to Jan. 2020

- Joseph Wagner – Jan. 2020 to present

COO Turnover – 3 COOs over the last 4 years[2]

- Wilson Keenan – Jul. 2016 to Aug. 2017

- Varsha Rao – Sep. 2017 to Dec. 2018

- Jamie Reynoso – July 2020 to present

General Counsel Turnover – 2 GCs in the past 3 years

- Brady Priest – June 2016 – Sept. 2018. Since Sept. 2018, Priest’s LinkedIn says he has been an advisor to the company and that in July 2020 he became CEO of Seek Medicare.

- Gia Lee – Jan. 2019 to present

Part IV: How Clover CEO Vivek Garipalli Created Clover With Money ‘Siphoned’ From The Healthcare System

Prior To Founding Clover, CEO Vivek Garipalli Owned A Group Of New Jersey Hospitals Through His Holding Company CarePoint Health

In the lead up to Clover’s go-public transaction, Chamath Palihapitiya described Clover CEO Vivek Garipalli as “an absolute proven moneymaker.” In this section we examine just how Garipalli made his money.

Garipalli had previously founded CarePoint Health, an entity that bought three distressed hospitals in northern New Jersey. CarePoint started with its 2007 acquisition of Bayonne Medical Center, later purchasing Hoboken University Medical Center and Christ Hospital in Jersey City.

In fact, Clover was formed out of CarePoint as a provider-sponsored insurance plan, originally named CarePoint Investments. [Pg. 4]

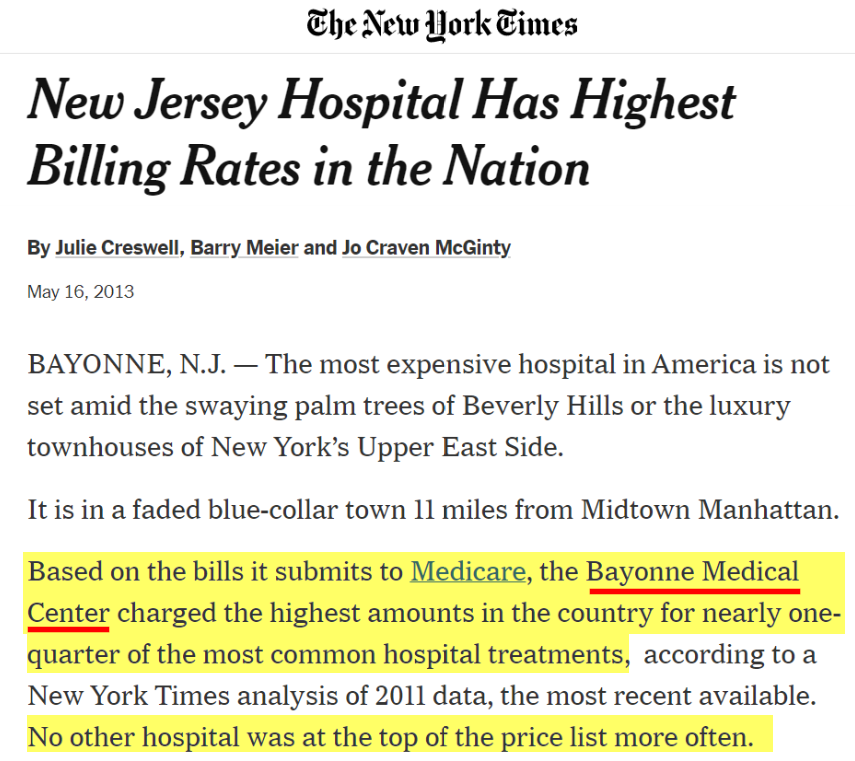

Under Garipalli’s Oversight, One CarePoint Hospital Charged The Highest Prices For Emergency Room Treatment In The Country

In New Jersey, insurance companies must pay for emergency room visits, even if a hospital is out-of-network. This created an obvious loophole whereby hospitals could avoid establishing network relationships with insurers, then charge higher prices.

Given the implications for sustainable patient care, most hospitals chose not to exploit the loophole, and apparently none exploited it to the extent that Garipalli did.

A 2013 New York Times article found that Garipalli’s Bayonne Medical Center charged the highest rates for emergency visits out of every hospital in the country.

Per the article:

“’Their model is to charge exorbitant rates, particularly for emergency room services, and if the insurance companies don’t pay them, they threaten to go after the member for the balance of billing,’ said Carl King, head of national networks for Aetna”.

One Example: Garipalli’s Hospital Charged a Teacher $9,000 For A Bandaged Finger And a Tetanus Shot

Another article described how one patient was billed $9,000 to have a cut on his finger bandaged at the Bayonne ER. The patient explained:

“’I got a Band-Aid and a tetanus shot. How could it be $9,000? This is crazy,’ Hanusz-Rajkowski said. ‘If I severed a limb, I’d carry it to the next emergency room in the next city before I go back to this place.’”

In another example, Bayonne charged $17,000 for 5-6 stitches for a man who cut his hand.

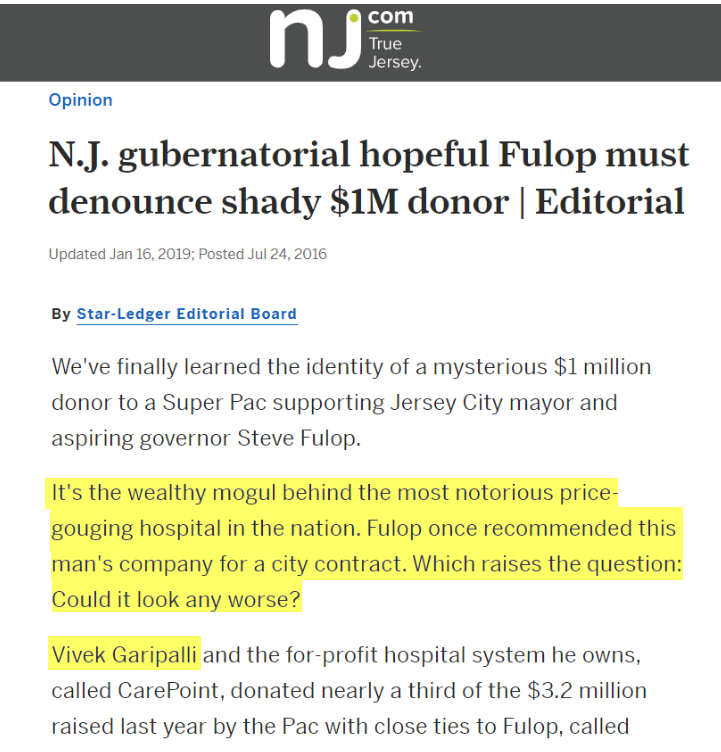

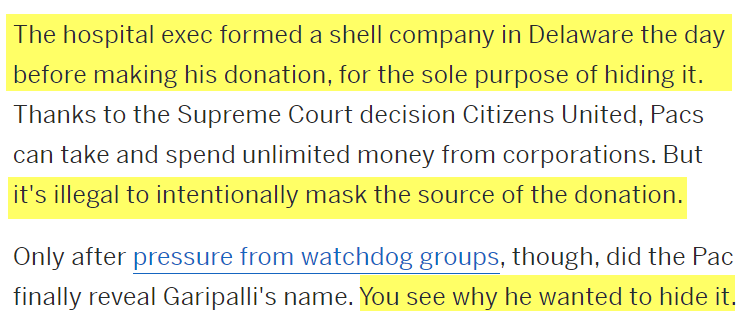

In 2015, Coming Under Increasing Regulatory Scrutiny, Garipalli Made a Secret $1 Million Donation to the Jersey City Mayor Through a Shell Entity

Garipalli Was Revealed as the Donor Only After a Non-Profit Sued to Expose the Records

As scrutiny picked up on Garipalli’s hospital network, he made a large donation to the mayor of Jersey City, where CarePoint (and now Clover) operate.

On December 23, 2015, unnamed owners formed a Delaware entity called DE First Holdings, LLC. The next day, the entity donated $1 million to a Super PAC supporting the mayor of Jersey City, according to litigation records.

A non-profit group focused on government transparency later sued the Federal Election Commission to force disclosure of the records. The use of a shell entity to mask a political donation is a violation of campaign finance law, according to the complaint.

The records were eventually released, revealing that Garipalli had formed the entity in an apparent effort to hide the donation. Local media laced into the mayor over the “shady” deal:

—————————————

It was not the first time Garipalli had to answer questions about undue political influence.

In 2011, around the time Garipalli attempted to close the original deals to purchase the CarePoint hospitals, a local assemblyman was revealed to have accepted maxed-out donations from Garipalli’s parents. The assemblyman eventually donated the money to charity after local media identified the conflict of interest.

In 2019, New Jersey Regulators Detailed How Garipalli Siphoned Over $157 Million From His Price-Gouging Hospital Network Through a Series of Shell Entities

Garipalli’s hospitals earned massive profits through its price gouging model, but an investigation later revealed that Garipalli siphoned the money out of the hospital systems through a series of shell entities.

In March 2019, the New Jersey Commission of Investigations released a detailed report explaining how Garipalli and his associates used a byzantine network of LLCs to extract over $157 million from CarePoint’s hospitals.

The network of entities was so complex that it masked from the Department of Health (DoH) the existence of a $60 million loan, limiting the DoH’s ability to evaluate the potential risks it posed to the viability of the hospitals. [Pg. 21]

The report followed an earlier 2014 report by Healthcare lobbying organization HPAE, which raised questions about why Bayonne’s “services and staff have been cut, contracts with insurance companies cancelled, and the hospital buildings and property sold to a real estate investment trust in an opaque and unregulated sale-leaseback arrangement.”

By 2020, After the Money Was Extracted, CarePoint’s Hospitals Collapsed Financially. Legislators Then Demanded an Investigation into Clover Health and Other Related Entities.

Clover Has Not Disclosed Whether It or Garipalli Are the Subject of Any Specific Investigations

In February 2020, all nine state legislators from Hudson County, New Jersey, wrote the governor demanding an investigation into CarePoint, Clover Health, and affiliated entities over the siphoned funds, which had left the hospitals in dire financial condition:

“The near bankruptcy of the CarePoint hospitals is directly related to the decision by ownership to withdraw unreasonably large sums from their operations for personal profit at the detriment to services and the health care available to Hudson County residents.”

The letter detailed how one of CarePoint’s hospitals was on the verge of bankruptcy and another was weeks away from insolvency, and requested aggressive action from the governor, including passage of legislation to prevent similar abuses in the future.

Garipalli And Others Earned the Title of “Vampire” In A Recent Local Newspaper Editorial Opining on The Business Model and Sale Process of The Distressed Hospitals

The Jersey Journal had this take on Garipalli’s more than 10-year history overseeing the three hospitals in a June 2020 editorial, which argued that greed and self-dealing were holding up a sale of the hospitals after years of questionable dealings:

“It’s high time for all the dickering to come to an end, for the vampires to stop their feeding, and for the healthcare mission of these three hospitals to be put at the top of the list for new owners.”

The hospitals were prepped for sale, which predictably resulted in layoff notices being sent to 2,700 hospital employees along with 45 layoffs at CarePoint.

The state’s investigation into CarePoint’s finances and use of shell companies that concealed debt and enabled the siphoning of $157 million prompted the passage of 3 state laws aimed monitoring the suitability of any management fees, along with improved transparency.

The hospitals are still in the process of being liquidated and sold to new owners, per recent media reports.

Despite the Chaos, Garipalli Appeared To Come Out A Winner, Promptly Purchasing An $11 Million Mansion in the Hamptons

CarePoint didn’t leave a lot of winners in its wake.

Patients who were charged $9,000 for a bandage or $17,000 for a stitched finger didn’t come out ahead. The healthcare system and taxpayers that shouldered most of the costs didn’t come out ahead. The CarePoint hospitals that are being sold in a messy liquidation, and the laid off employees certainly didn’t come out ahead.

But Vivek Garipalli seemed to come out great. He purchased an $11 million beachfront mansion in the Hamptons in 2011, which was recently assessed at over $34 million.

Some investors, like Chamath, may interpret Garipalli’s path as being that of a “moneymaker”. But investors in Clover who think they are investing in a disruptive technology company may want to understand how Garipalli’s money has been made, and whether the style of vulture capitalism is one that is likely to lead to reward for shareholders other than himself.

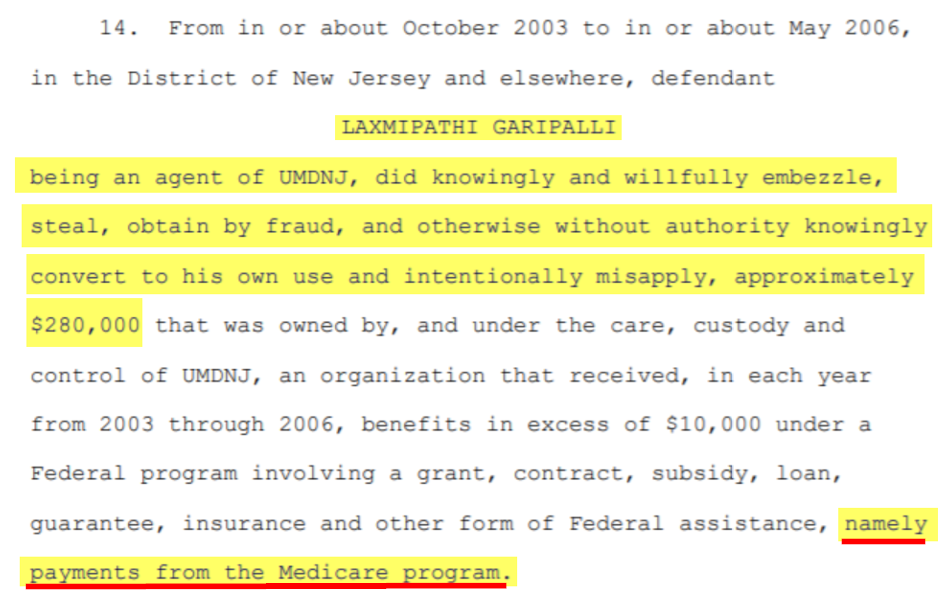

Clover’s Prospectus Notes That Garipalli is “The Son of Two Doctors”

It Failed to Mention That Garipalli’s Father Pled Guilty to Criminal Fraud Charges Over Allegations of Embezzling Funds from a Hospital That Was a Beneficiary of Medicare

Clover’s prospectus noted that Garipalli is “the son of two doctors”, presumably giving him added insight into the medical system. [Pg. 244]

The prospectus failed to mention that one of those doctors, Garipalli’s father, pled guilty to criminal fraud charges in New Jersey over allegations of embezzling funds from a hospital that was a beneficiary of Medicare.

————————————————————————

We do not believe the sins of a father are necessarily applicable to the son, but we find the context may be relevant, particularly given the evidence we have uncovered about Clover.

We Have 18 Questions For Clover’s Management That We Think Investors Deserve the Answers To

- Did Chamath and/or Clover know about the ongoing DOJ investigation? If so, why was it concealed from investors?

- Is Clover aware of any other regulatory investigations into the company or Vivek Garipalli and his related companies? If so, what are the details?

- Has Clover received any subpoenas or civil investigative demands from regulators? If so, how many and from which regulators?

- Why does Clover’s subsidiary, “Seek Insurance” operate a website called “SeekMedicare.com” claiming to offer “independent” and “unbiased” advice on selecting Medicare plans without disclosing that it is owned by a Medicare plan provider, representing a blatant conflict of interest?

- Clover’s subsidiary, Seek Insurance, claims on its website “We don’t work for insurance companies. We work for you” despite literally being owned by Clover, an insurance company. What is your response?

- How much has Clover paid B&H Assurance, the undisclosed outside brokerage firm run by Hiram Bermudez (its Head of Sales) since inception?

- What portion of Clover’s business has been referred by B&H Assurance since inception? How many members?

- Former employees told us that the relationship between Clover and B&H Assurance was transferred into the name of Hiram Bermudez’s wife “for compliance purposes”. NAIC filings confirm it was transferred into his wife’s (maiden) name weeks after the go-public announcement. What is the explanation for this?

- Will Clover produce the agreement showing the transfer of the relationship into Hiram Bermudez’s wife’s name? Who signed off on the agreement and which senior members of management knew about the deal?

- Is Clover aware that disclosure of significant transactions with key senior employees is something investors like to know about, so they can be made aware of potential material conflicts of interest?

- Was Chamath aware that the DOJ was looking into issues of potential upcoding when he mentioned, unprompted, on CNBC “they don’t motivate doctors to upcode or do all kinds of things in order to get paid”?

- Clover reported that “onboarded” physicians used Clover Assistant for 92% of member visits in 2019, but never defined “onboarded”. We found that less than half of Clover’s in-network doctors are considered “Clover Preferred”. What is the definition of an “onboarded” physician? What percentage of Clover’s in-network doctors actually use the Clover Assistant?

- If Clover’s software is so “delightful” to use, why does Clover have to pay doctors extra ($200 per visit) just to use it?

- Multiple doctors explained that it was difficult to remove prior diagnoses from the Clover Assistant. Is Clover aware of this? And can Clover guarantee that in future versions of the software doctors will be able to remove prior diagnoses, so as to ensure accuracy and cost efficiency?

- A former employee explained that Clover handed out gift cards to doctors and nurses to generate patient leads, a practice prohibited by CMS. These gift cards were justified as being for everything but recruitment, including “morale,” a “thank you,” “motivation,” and “friendship.” How do you respond?

- Does CEO Vivek Garipalli deny that his CarePoint hospitals at one point charged the highest emergency room prices in the entire nation?

- Why did CEO Vivek Garipalli make a secret $1 million donation to the Mayor of Jersey City?

- Why has Clover had such extensive executive turnover, with 3 CFOs, 3 COOs, and 2 General Counsels in the last 4 years?

Conclusion: Do Short Sellers Play A Role In A Healthy Market?

Despite nearly 4 months of due diligence we performed and financed for this report, we have no position in Clover.

Why? Because while short selling is always high risk, these are unprecedented times; many people are angry and right now we believe it is important to demonstrate the role short sellers play in a healthy, functioning market.

Usually, the gripe with short sellers is the business model (i.e.: making money when a stock goes down). We are taking that off the table for this one report so the investing public can more clearly see the work for what it is; deep-dive investigative research.

Critical, adversarial research is needed because Wall Street is a finely tuned machine, built to sell securities to the public, regardless of quality. In short, the corporate world is rife with fraud, and investors have little protection:

- Companies love to tout their accomplishments, but they don’t put out press releases announcing that executives are stealing, putting dangerous products on the market, or bribing politicians (unless they get caught).

- Investment banks almost exclusively issue glowing “buy” ratings on stocks, hoping to turn around and sell those same securities to the public, an inherent conflict of interest.

- Auditors. Many new investors (wrongly) assume auditors are their protection against fraud, despite the leadership of audit firms publicly acknowledging that it is not their job. When auditors do stumble onto fraud, they generally quietly resign without saying anything, rather than illuminating the investing public to the issues. Auditors are paid by the companies they audit—did you really think they work for you?

- Regulators. Many new investors assume regulators are like police, responding immediately. In reality, regulatory investigations usually take 3-5 years and generally begin only after exposure of a fraud and after victims have already lost money. Regulators can serve as an effective deterrent, but rarely as protection.

- Investigative journalists play an important role, but traditional financial journalism has been slowly dissipating due to the changing media business model. Notably, business journalists like Dan McCrum, Roddy Boyd, and Jon Carreyrou serve as examples who have made exceptional contributions over the last decade.

Given the dynamics above, short sellers, like us, have stepped further into the role. This model has existed for hundreds of years, and it’s the reason why short sellers have been instrumental in exposing most major market frauds in recent history, including Enron (2001), Tyco (2002), systemic mortgage fraud (2008), Lehman Brothers (2008), Valeant Pharmaceuticals (2015), MiMedx (2017), Luckin’ Coffee (2020), Wirecard (2020), and Nikola (2020).

We spend months researching malfeasance and when it comes time to publish, we align our research with our capital and bet against wrongdoing. Just as “long” investors go on TV or publish their reasons why they think their investments should increase in value, we share our detailed reasons why we think our “short” investments should decrease in value. Our proceeds help fund future investigations and research.

Sometimes this all gets lost in the noise because short selling is often associated with “controversy”.

Every report we publish is “controversial” because we threaten the interests of powerful corporations and individuals. This report is no different—we expect the company and Chamath to issue a scathing response. (We anticipate he may say something like “this is the system pushing back on me for speaking the truth”– it’s what a populist would say.) It won’t be the first time we’ve upset billionaires and it won’t be the last.

Some people will be angry with us. Others will support us, for a variety of good and bad reasons. We welcome all of it because we think a free and open exchange of ideas creates a more vibrant marketplace and a more vibrant democracy.

Legal Disclaimer

Use of Hindenburg Research’s research is at your own risk. In no event should Hindenburg Research or any affiliated party be liable for any direct or indirect trading losses caused by any information in this report. You further agree to do your own research and due diligence, consult your own financial, legal, and tax advisors before making any investment decision with respect to transacting in any securities covered herein. As of the publication of this report, Hindenburg Research has no position in any stocks (and/or options of the stock) covered herein. To our knowledge, none of our members, partners, affiliates, employees, and/or consultants, clients and/or investors have any positions in the stocks (and/or options of the stock) mentioned herein. This is not an offer to sell or a solicitation of an offer to buy any security, nor shall any security be offered or sold to any person, in any jurisdiction in which such offer would be unlawful under the securities laws of such jurisdiction. Hindenburg Research is not registered as an investment advisor in the United States or have similar registration in any other jurisdiction. To the best of our ability and belief, all information contained herein is accurate and reliable, and has been obtained from public sources we believe to be accurate and reliable, and who are not insiders or connected persons of the stock covered herein or who may otherwise owe any fiduciary duty or duty of confidentiality to the issuer. However, such information is presented “as is,” without warranty of any kind – whether express or implied. Hindenburg Research makes no representation, express or implied, as to the accuracy, timeliness, or completeness of any such information or with regard to the results to be obtained from its use. All expressions of opinion are subject to change without notice, and Hindenburg Research does not undertake to update or supplement this report or any of the information contained herein.

[1] Chamath also controls 284,891 Class B shares purchased for an unknown price through an earlier private venture round, per the prospectus ownership table. [Pg. 8]

[2] Note there is a gap from December 2018 to July 2020. It is unclear whether Clover had another COO during that time or whether a different member of the executive team temporarily took on those responsibilities.

499 thoughts on “Clover Health: How the “King of SPACs” Lured Retail Investors Into a Broken Business Facing an Active, Undisclosed DOJ Investigation”

Comments are closed.

Thanks, I love your dedication to researching and the professionalism you put into the work.

I’m sure you can probably expect a cease and desist along with defamation lawsuits from multiple parties on this report. This article was just shameful.

It seems like someone is heavily invested in CLOV. Feel sorry for you. Good luck!

And refreshingly revealing. I applaud the brutal honesty from Hindenburg. Your comment was unnecessary.

Nice work. The initial eyebrow raising moment for me was the q&a on cnbc when Andrew asked chamath about mlrs and chamath responded “meaningfully better” than competition. Neither one of these guys had a clue about medicare mlrs. Oddly, I could not find clover’s mlr filing on cms website but did review naic for their New Jersey health plan and certainly there’s nothing special there. I am surprised you did not mention this in report as it seems to be fraudulent statement or maybe Chamath is correct? Thanks

https://i1.wp.com/hindenburgresearch.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/02/35.png?resize=768%2C521&ssl=1

is a huge house man

Hey shorty, how are the borrow fees? You and your cronies working with MMs on ladder attacks make you feel good? Enjoy the squeeze, shorty. I’ll be eating tendies outside of your prison cell.

you idiot, if you read the article all the way through you would see he has no position in Clover

Borrow fees are pretty inexpensive when he *has no position in Clover*

He literally gave away four months of research for free, for no financial benefit to himself – just to make a point.

Have fun squeezing someone who is sitting on the sidelines eating popcorn and watching.

Your name looks accurate, were you dropped on your head as a child or are you going deranged waiting for your benefits to kick in after losing your entire $1,259.13 net worth buying GME at the top?

Drooling moron, indeed

What an idiot. THEY DON’T EVEN HAVE ANY POSITIONS IN THIS, DOUCHEBAG

You and your team are freaking awesome. Keep up the good work!

Wow, breaking news this entire thing wasn’t covered on reddit a month ago https://www.reddit.com/r/SPACs/comments/kssgb4/dangers_to_be_aware_of_ipoc_soon_to_be_clov/

Dear Hindenburg,

Your reports are usually great. I appreciate all the effort you punt into investigating these frauds. I personally think CLOV is a fraud that will keep on generating money, so it would be risky to bet against them. That said, on your final conclusion for this report, you should acknowledge that short sellers, like Wall Street companies, also have quite a fair share of greedy wolves that serve the interests of their clients (usually other Wall Street whales attacking each other). If you did this, you could show that your views are aligned with the “human” investors, as you have claimed.

Thank you for your time,

David

P. S. : your MVIS piece was a flunk. After several days doing DD prior and post, I think you failed to acknowledge the potential of the technology. But, it’s alright. I feel you did it with good intentions. I was quite skeptical at first for MVIS. And not everything is black and white.

I hope they payed you well for this obvious hitpiece to drive prices lower so big money can re-enter

Thank you for your fortitude in making public your short thesis in these times when short sellers have come under scrutiny from the public. You’re showing the value short-sellers bring to a healthy market by doing in-depth research on companies and unveiling fraudulent or misleading claims and practices. I was long CLOV before reading this, seems you may have saved me from some significant losses. Keep up the great work!

Not sure if this was something you looked at, but it’s interesting that Summit (the #1 preferred provider) recently completed a private equity (Warburg) backed merger with CityMD.

A popular PE strategy over the past decade has roll-ups of physician networks with the sponsor ‘improving’ EBITDA margins by implementing aggressive upcoding/billing practices — a strategy that’s so popular Congress even looked into it.

Clover’s upcoding and kickback strategy seems like it would fit nicely into a sponsor-owned practice. Wouldn’t be surprised to find out there was more there on that relationship, and other PE ones like it, than meets the eye

CLOV will now fall faster than Melvin capital lost billions in GME.

Who performed the investigation? Was it employees of Hindenburg? Was any part of the research/investigation conducted by anyone affiliated with other hedge funds or those with short positions in $CLOV?

How do we know this report wasn’t compiled by short interests and simply handed off to Hindenburg?

No coincidence that this came out after Chamath came out against the shorts with GME. Gotta get back at him aye? You should have delayed this considering the context. Makes you seem petty.

Chamath upset you all by thumbing his nose at short-sellers last week alongside/r/wallstreetbets in the $GME craze, and you’ve retaliated with a hit-piece. It is hard to take this report at face value. I think you’re focusing intensely on the business/operational mistakes they’ve made along the way, but you’ve done nothing to underscore the validity of the market or their business model. I’m down the street from them, and I can confidently say that there is an enormous opportunity in the MA space. Evidence-based medicine is a robust growth trend, and the assistant not the only software play they’ve made. They also offer telemedicine and other unique software-based approaches to make MA plans more operational, efficient, and accessible. Getting provider buy-in and establishing yourself is exceptionally challenging, and they have accomplished a lot. Time will tell what the opportunity looks like deploying a software technology in the MA space. What evidence do you have to speak to that?

If it sounds too good to be true, it usually is.

I appreciate discriminating assessments when allocating my hard earned capital.

Thank you.

High regard to Hindenburg Research for exposing fraud and insight into potential corporate malpractice. As retail investor who invest own money and taking risk, we must appreciate authentic and deep research done by investigative journalist as to gives inside view of how corporate works. In light doing so, enabling us to make better financial decision and due diligence just as mutual funds and hedge fund manager did.

As usual, a very thorough and thought provoking report.

Sad times when retail investor sentiment (Reddit) threatens the very institutions who have been fighting the fight they lay claim to for many years.

The job you do is very thorough and well processed. Some law enforcement agencies should be as thorough. But then you are also looking for your point of view and might not so unbiased.

With that said, I think what bothers me about your research is that by the time the information comes out, the stock price has already been dropping for a few days. The same has happened numerous times already.

Are you guys the only ones shorting, are you shorting that heavy and want one last drop, or is the information leaking early to a few others to performa a collaborated effort in profits?

Research like yours is the closest thing we have to whistleblowing in the securities industry. As with the more traditional types of whistleblowers that we see in other industries, often they point to real problems, but sometimes they get it wrong. I’ll be interested to see the future of this report — but whether this particular research is directly on-target or not, I think you’re providing a public service and thank you for it.

Keep up the great work!

They create transparency. They don’t play games. They don’t motivate doctors to upcode or do all kinds of things in order to get paid.”

– Chamath Palihapitiya (1:07-mark)

Mr. Milton unveiled a semi truck, called the Nikola One, in 2016, and said it was operational. “It’s not a pusher,” Mr. Milton said at the event, using an industry term for a mock-up vehicle that cannot be driven and must be pushed.

I am strangely drawn to comparing these two disparate statements, both offered by the chief promoters of their respective companies, without being asked for by the interviewer. It may be something, it may be nothing, but it makes me question the validity of the first statement based on what we later found out about the second statement.

Wow. Painful to read. Ultra subjective and pitiful in some cases. Best of luck in the future. Ouch.

Okay, Palihapitiya

So Clover basically does what United Health Group and Optum have been doing for over a decade. They mislead seniors, make under the table payments to brokers and pay physicians to upcode so their risk scores and revenue increases. They make more money while Medicare (e.g. taxpayers) watch and drool.

This is why prudent, objective & independent research firms like Hindenburg Research are so much needed in a free market system, to uncover frauds, help facilitate the efficient flow of capital, improve price discovery practices and improve overall capital market operations!

ARS and CNBC remain “clueless” and are blinded by their own myopic agendas!

Thank you Hindenburg! While not perfect (who is) and not without a profit incentive (no one is), this is research team that warrants attention & prudent investors consideration! Be blessed!